Sixties Scoop Apprehension of Indigenous Children without Consent

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...

We would like to acknowledge that this article was framed from the research and writing of authors Maureen Lux (Separate Beds: A History of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s - 1980s) and Gary Geddes (Medicine Unbundled: A Journey Through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care).

In this article, we use 'Indian' as that was the term used at the time. For information on appropriate terminology, download our free ebook “Indigenous Peoples: A Guide to Terminology.”

The history of Indian hospitals (the 1920s - 1980s) in Canada is not as well known as that of residential schools but is as horrific in both its actions and the implication of those actions. This aspect of Canadian history shows that care for the health of Indians was never a priority and never on par with the care available for Europeans. Health care for Indians, such as it was, was motivated by a number of factors that range from keeping as many patients 'interned' as possible, to maintaining government funding, ensuring a steady number of subjects for medical and nutritional experiments, and ensuring that the European population was protected from exposure to 'Indian tuberculosis.'

Repeatedly referring to the disease as “Indian tuberculosis,” a common practice among bureaucrats and the medical professionals in the Canadian Tuberculosis Association, was tantamount to racial profiling, and indeed pathologized the very notion of Indianness. [1]

Segregated medical treatment for Indian patients was the norm in community hospitals where they were treated in the basement or 'Indian annexes' but the outbreak of tuberculosis (TB) introduced segregation on a larger scale.

Death rates in the 1930s and 1940s were in excess of 700 deaths per 100,000 persons, among the highest ever reported in a human population... Tragically, TB death rates among children in residential schools were even worse. [2]

It is important to understand the symbiotic connection between the high incidence of TB in Indians and residential schools. Many of the residential schools, with overcrowding, malnutrition, and lack of heat were fertile sites for the rampant spread of the highly communicable tuberculosis virus. Children who became infected were sent to the Indian hospitals, and when they showed signs of recovery, were sent back to the residential school. This mutually beneficial arrangement maintained the numbers and funding of both organizations.

Just as it was legal under the Indian Act to apprehend Indian children and put them in segregated (residential) schools it was legal to apprehend Indians suspected of having TB and quarantine them. Interestingly, that part of the Act remains today.

Not yet having achieved the status of “persons,” never mind citizens of Canada, they were susceptible to quarantine or incarceration at the whim of doctors, Indian agents, or government officials. Declaring individuals contagious was a good means of control, keeping them out of trouble or out of circulation while the task of clearing the land was underway. [3]

In some centres, the local doctor was also the Indian agent.

INDIAN ACT, 1876REGULATIONS

Marginal note: Regulations

(h) provide compulsory hospitalization and treatment for infectious diseases among Indians;

- 73. (1) The Governor in Council may make regulations

INDIAN ACT, 1985Regulations

(h) to provide compulsory hospitalization and treatment for infectious diseases among Indians;

- 73 (1) The Governor in Council may make regulations

There also were examples of experimental treatment of tuberculosis. Records were poorly kept but some patients speak of having a lung removed which involved having sections of their ribs connecting to their spines cut off - an operation routinely performed with just a local anesthetic. As ribs don’t regenerate, those who suffered through and survived these operations were left crippled, both physically and emotionally.

The bacillus-Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine for tuberculosis was tested on patients in the Fort Qu’Appelle Sanatorium in the early 1930s by Dr. R. George Ferguson:

In 1933 Ferguson, funded by Indian Affairs and the National Research Council, began an experimental vaccine trial on local Aboriginal infants. His twelve-year study was an apparent success: only six of the 306 children in the vaccinated group developed tuberculosis and two died; while 29 of the 303 in the control group developed tuberculosis and nine died. But Ferguson’s research also revealed that 77 of the 609 children in the trial, or more than 12 percent, died before their first birthday, while only four of these were tuberculosis deaths (two in each of the vaccinated and control groups.) In all, nearly one-fifth of the children in the trial died from other diseases, mostly gastroenteritis and pneumonia. Poverty posed the greatest threat to children, but unlike tuberculosis, it did not spread to white communities. BCG lived up to its promise to control tuberculosis while leaving untouched the socio-economic conditions that led to its rise. [4]

For more on the BCG vaccine and its use in Indigenous communities, please read Bacille de Calmette-Guérin, or BCG Vaccine for Tuberculosis

One of the founding principles supporting the establishment of hospitals for the sole treatment of Indians was that they would be run cost-efficiently. That underlying principle led to the majority of staff being poorly trained healthcare workers. Doctors were not interested in working in remote, isolated, poorly funded, inadequate Indian hospitals when they could work in major centres.

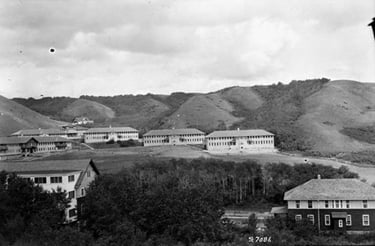

The buildings were often redundant military barracks haphazardly repurposed as hospitals. These buildings generally lacked the most basic features of hospital facilities of the era and were run with inadequate laundries, inadequate kitchens and poor maintenance - inadequacies that exacerbated the symptoms of the patients.

As with residential schools, the last of which closed in 1996, Indian hospitals are not ancient history. The lingering impact of undergoing 'treatment' at an Indian hospital has resulted in many elderly Indians having a deeply rooted fear and distrust of medical personnel.

NOTE: In 2019, former students of Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet in what is now known as Nunavut won a court battle to have Kivalliq Hall included as an IRSSA-Recognized School. While this 2017 article states that the last residential school in Canada to close was in 1996, Kivalliq Hall's closing in 1997 is an important detail to note when recounting and learning about Indigenous history.

It could also be argued that racism in the medical system today towards Indian patients has its roots in the history of Indian hospitals.

This article touches on just some of the many aspects of Indian hospitals. It is an expansive topic that deserves much more exploration and exposure.

[1] Gary Geddes, Medicine Unbundled, A Journey through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care

[2] TB and Aboriginal People, Canadian Public Health Association

[3] Gary Geddes, Medicine Unbundled, A Journey through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care

[4] Maureen Lux, Bacille de Calmette-Guérin, or BCG Vaccine for Tuberculosis

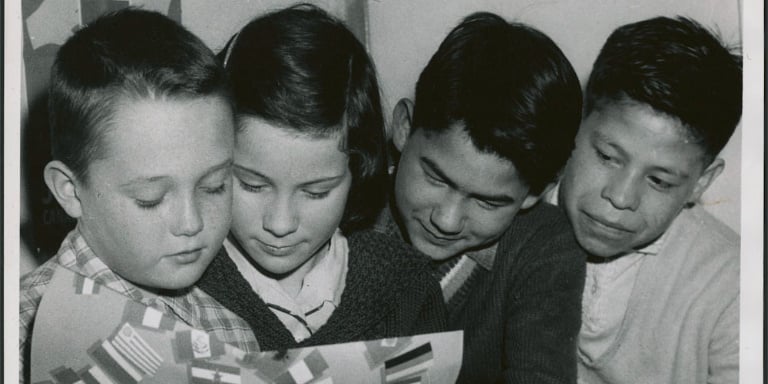

Featured photo: Dene children in hospital. Photo: John Lewis Robinson / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / Library and Archives Canada / a102238-v6

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...

1 min read

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its summary report and findings on June 2, 2015, after six years of hearings and testimony from more...

In 1844, the Bagot Commission of the United Province of Canada recommended training students in “…as many manual labour or Industrial schools as...