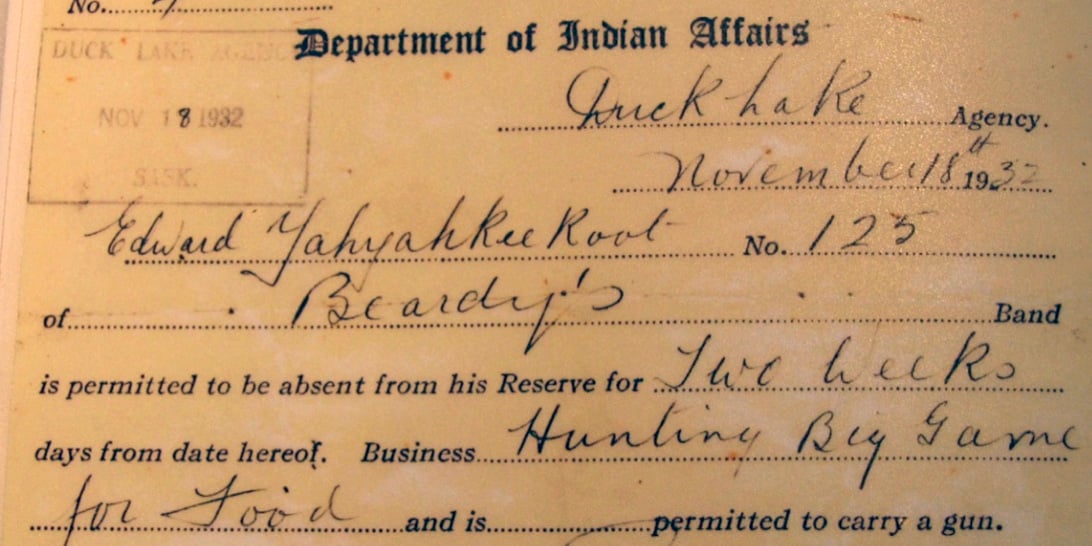

21 Things™ You May Not Have Known About the Indian Act

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other...

There are lots of lore and misconceptions about First Nation totem poles. In this article, we address six of the more common misconceptions.

Carving and erecting totem poles is not a pan-Indigenous tradition but is specific to the west coast in regions in which the magnificent western red cedar tree grows.

Why is western red cedar the primary wood used by carvers? Because specimens can reach tremendous heights in the lush west coast forests, have a straight grain, and are much slower to succumb to the elements than other trees, such as a Douglas fir.

You may see totem poles in other regions of Canada, and indeed, all over the world but those are poles that have either been gifted by a nation, commissioned, purchased, or were taken from communities and have not yet been repatriated (returned).

Not everyone within a community that has totem poles is a carver. Most of the legendary carvers were steeped in the craft from an early age. You may hear references to someone being from a “carving family.”

Each tree is unique and presents unique artistic challenges and opportunities. Carvers understand how to work with the grain of the tree and how to use the grain and colouration of the wood to evoke movement and emotion in the carving.

In many cultures, before a tree is harvested for a pole or post, a ceremony is conducted to give thanks and show respect. Trees are typically harvested from the traditional land of the carver but communities do make gifts of logs to other communities for poles and posts.

Non-Indigenous people can and do carve totem poles for a variety of reasons but, it’s a larger issue than “can” someone, who isn’t from a First Nation carving culture, carve a totem pole. The larger issue is the rampant appropriation of Indigenous culture.

And mixed in with the issue of appropriation is the contradiction of a society that largely ignores Indigenous Peoples yet covets and copies aspects of their culture, occasionally for monetary gain, and often without any recompense to the people whose culture they are exploiting.

Carving is more traditionally the domain of men but in some cultures, women also carve.

Ellen Neel (1916 - 1966) a Kwakwaka'wakw carver, is considered the first woman to publicly carve and sell her work. In 1948, the Stanley Park Parks Board gave official permission for her to open a studio in the park. The date is interesting as the Potlatch Ban, which drove Indigenous culture, ceremonies and traditions underground, was not lifted until 1951. But, it is equally astounding because, at the time, it was almost unheard of for an *Indian woman to rise out from beneath the gender-biased policies of the Indian Act and establish a business.

*I use Indian here as that was the term used in the Indian Act in that era.

Totem poles don’t tell stories - they document notable events, commemorate ancestors, and define rights, and lineage.

Designs or crests that are used traditionally belong to a clan or family - one family cannot use the crests or designs owned by another. There are complex rules that protect ownership and deep histories involved in those rules.

This assumption has oddly spawned a colloquialism that is commonly heard in the corporate culture. How totem poles became associated with the career movement could be attributed to a book called “Low Man on a Totem Pole” (1941) by H. Allen Smith and published by Doubleday, Doran. The book isn’t actually about totem poles but its cover depicts a cartoonish image of a totem pole.

The figures at the base are, contrary to the colloquialism, the most significant. The size of the figure at the bottom of the pole is generally the largest because the girth of a tree is biggest at its base. These figures are at eye level so are more visible than the figures or crests further up the pole. Some poles are over 30 meters high so logically why would the most important figure - the one highest on the totem pole - be positioned where it could not easily be seen

“Low rung on the ladder” - is a more relevant term to use if you want to talk about climbing the corporate ladder.

This misconception stemmed from Christian missionaries who misunderstood the purposes of the poles. They incorrectly assumed the poles were worshiped and that the designs were of pagan idols.

For those who would like to learn more about Indigenous history, culture and relations, our Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® course is a great place to start. It can be taken in a Self-Guided, Live-Guided Virtual, or In-Person format.

Featured photo: Unsplash

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other...

Randomly plucking “popularized” images of a marginalized culture for entertainment or profit without respect for or an understanding of the culture...

How long do you think First Nations have been fighting against the inequitable treatment of First Nation women by federal government laws and...