Commercial Racial Profiling and Indigenous Peoples

As an Indigenous relations trainer, I strive to maintain a positive attitude that we are making progress on reconciliation. There are setbacks but I...

The Commission believes that in the coming years, media outlets and journalists will greatly influence whether or not reconciliation ultimately transforms the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. To ensure that the colonial press truly becomes a thing of the past in twenty-first-century Canada, the media must engage in its own acts of reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples. [1]

Duncan McCue is the host of the CBC Radio One program Cross Country Checkup (he is currently away from CROSS COUNTRY CHECKUP on a Massey College journalism fellowship). Prior to taking this position in 2016, Duncan was a reporter for CBC News in Vancouver for over 15 years. His news and current affairs pieces are featured on CBC's flagship news show, The National. We went to Duncan for his perspective on the role of mainstream media and reconciliation.

What do you see as the primary role of mainstream media outlets in reconciliation?

If you were to ask any other journalist that question, they would likely be concerned by the very basis of the question. They would likely say: “It is not our role to be activists. We are truth-tellers covering events – so to suggest that we have a duty to report on stories of reconciliation is to misunderstand journalism.”

However, my response is that, by continuing to focus on stories of conflict and by under-reporting Indigenous issues in this country, journalists have been propping up the status quo of the colonial project for well over a century. So, whether they understand or believe it or not, they have been taking a stand. They have been, by the nature of the narrative frames they choose, propping up the policies that have prevented us from reconciling. It’s not a question of becoming activists when you go out and search for stories that have Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians deepening their relationships, or non-Indigenous Canadians making some sort of reparation. That’s not activism - that is expanding the kinds of storytelling that we have been doing.

Historically, mainstream media has supported the narrative of Indigenous peoples as victims and portrays them through a negative lens - of having social problems; poverty and associated impacts; focusing on tragedies, residential school abuses etc. Why do positive stories rarely make it onto the pages and screens of mainstream media?

My argument here is that there are more positive stories out there than people think there are. As journalists, we are very conscious of the critique that we are always focused on bad news – “if it bleeds it leads.” I think there is a lot of effort by mainstream media outlets to try to find positive stories. But we also are well aware of the consumption habits of news consumers. The reality is that stories about conflict and stories that anger people are the ones that often draw the most viewers. So those ones lead. The positive stories tend to be buried or are in the Lifestyle section of the newspaper so they just don’t get the same attention.

Unfortunately, in newsroom culture, journalists also tend to downplay those stories as ‘fluff.’

In your experience, is this changing?

Absolutely. It’s changing already. I am completely biased but if you look at the example of CBC Indigenous I think you will find a far broader range of stories about Indigenous issues than we ever had two years ago on CBC. The goal of CBC Indigenous is to present a wide selection of Indigenous life in this country and that doesn’t always mean conflict and ‘us-versus-them.’ You will see those kinds of stories because they exist. But you will also see “Boys with Braids”, Indigenous weddings – all kinds of other important aspects of Indigenous life that are news. If non-Indigenous Canadians are going to live side-by-side with Indigenous Peoples and be good neighbours then they have to understand all the aspects of Indigenous life, not just the same tired stories we’ve been seeing.

What is the significance of CBC online news programs changing editorial guidelines to capitalize Indigenous, Aboriginal, Native, and Indian? In your opinion, will we see other news outlets following form?

I think it is of huge significance because it’s recognition of what “Peoples” want to be called. It’s not unimportant to consider what people want to be called rather than dictating what they should be named.

It is also recognition of Nationhood.

Will other outlets follow? Yes, over time. You don’t see an outlet using the term “Indian” anymore outside of its legal, historical context. Slowly but surely journalists will come around to using the terms that we ourselves use – which is becoming Indigenous with a capital I.

Of course – it’s even more important that journalists take the time to include our tribal affiliations. We are not a homogenous group.

Is there an increase in Indigenous students pursuing careers in journalism? If not, why not?

Not nearly enough. I would love to report that we have Indigenous students beating down our door at UBC School of Journalism and all other journalism schools. But, the fact of the matter is, they are not. There are a number of reasons for this. First, education levels amongst Indigenous students are woefully below the standards of the rest of the country.

Unfortunately, there are some outstanding Indigenous storytellers who don’t see a place for themselves in newsrooms because they haven’t seen themselves represented in newscasts or in papers so why would they want to work in those places? And often for those who get over that, and recognize the power of the media, they are the only indigenous person working in that newsroom. That’s a very difficult hill to climb, especially if you are working in a place that doesn’t have cultural safety.

It’s going to be a long, slow journey before we see an increase in the number of Indigenous journalists. But I will say that I am on the jury of the Canadian Journalism Foundation Fellowship and have been thrilled by the small, but very talented, pool who apply for that fellowship each year because that means that there are, slowly but surely, in every region of this country one or two students who are determined to become journalists. I think within a generation we are going to see a big change.

Will their career paths be similar to non-Indigenous journalists?

I think all journalism students recognize that the Teutonic plates of journalism are shifting. What it means to be a journalist in 2016 is different from what it meant in 1990 when I was getting into journalism. It may mean a combination of freelancing, podcasting, multi-media creation and I think that’s a great fit for Indigenous students. A fact not well known in Canada is that we have an above-average number of entrepreneurs in Indian Country. Indigenous people are often drawn to careers where they are allowed to be independent to maintain their connections to community so being a freelancer, being able to design your own career fits in well with the goals for many young Indigenous people.

What do you think an increase in Indigenous journalists will mean for the overall picture of media in Canada?

A report just came out on the coverage of the missing and murdered Indigenous women and what they concluded was that Indigenous journalists from APTN or CBC or other outlets tended to have coverage that had far more context to it and was more reconciliation-oriented. As we see more Indigenous reporters I think you will see more historical context in Indigenous coverage and that coverage will be more solutions-oriented rather fixating on problems.

What top three recommendations do you have for mainstream journalists who cover news related to Indigenous Peoples?

Understand Indian time.

Understand ‘respect’ in an Indigenous context.

See #1.

What is your primary recommendation for mainstream media outlets to support reconciliation?

Journalists need to understand that we are not impartial players in the history of relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. The media have played a role in how colonialism evolved. If Canada is ever going to truly reconcile with Indigenous Nations in this country, the media will also play a role in making that reconciliation happen and it’s a critical role. We are helping educate Canadians about Indigenous realities in this country and we need to do it in a way that is fair, balanced and holistic – which is what we have not always done in the past.

Duncan McCue is a Correspondent with The National, CBC Television. He has been a reporter for CBC News in Vancouver for over 15 years. His news and current affairs pieces are featured on CBC's flagship news show, The National. He's also an adjunct professor at the UBC School of Journalism and has taught journalism to Indigenous students at First Nations University and Capilano College.

McCue was awarded a Knight Fellowship at Stanford University in 2011, where he created an online guide for journalists called Reporting in Indigenous Communities. Before becoming a journalist, Duncan studied English at the University of King's College, then Law at UBC. He was called to the bar in British Columbia in 1998.

Duncan is Anishinaabe, a member of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in southern Ontario. He lives with his wife and two children in Vancouver.

[1] Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, p. 19

Featured photo: Unsplash

As an Indigenous relations trainer, I strive to maintain a positive attitude that we are making progress on reconciliation. There are setbacks but I...

Uncivil dialogue in Canada is alive and well, if only as indicated by the nature of the statements and conversations that take place in the comments...

1 min read

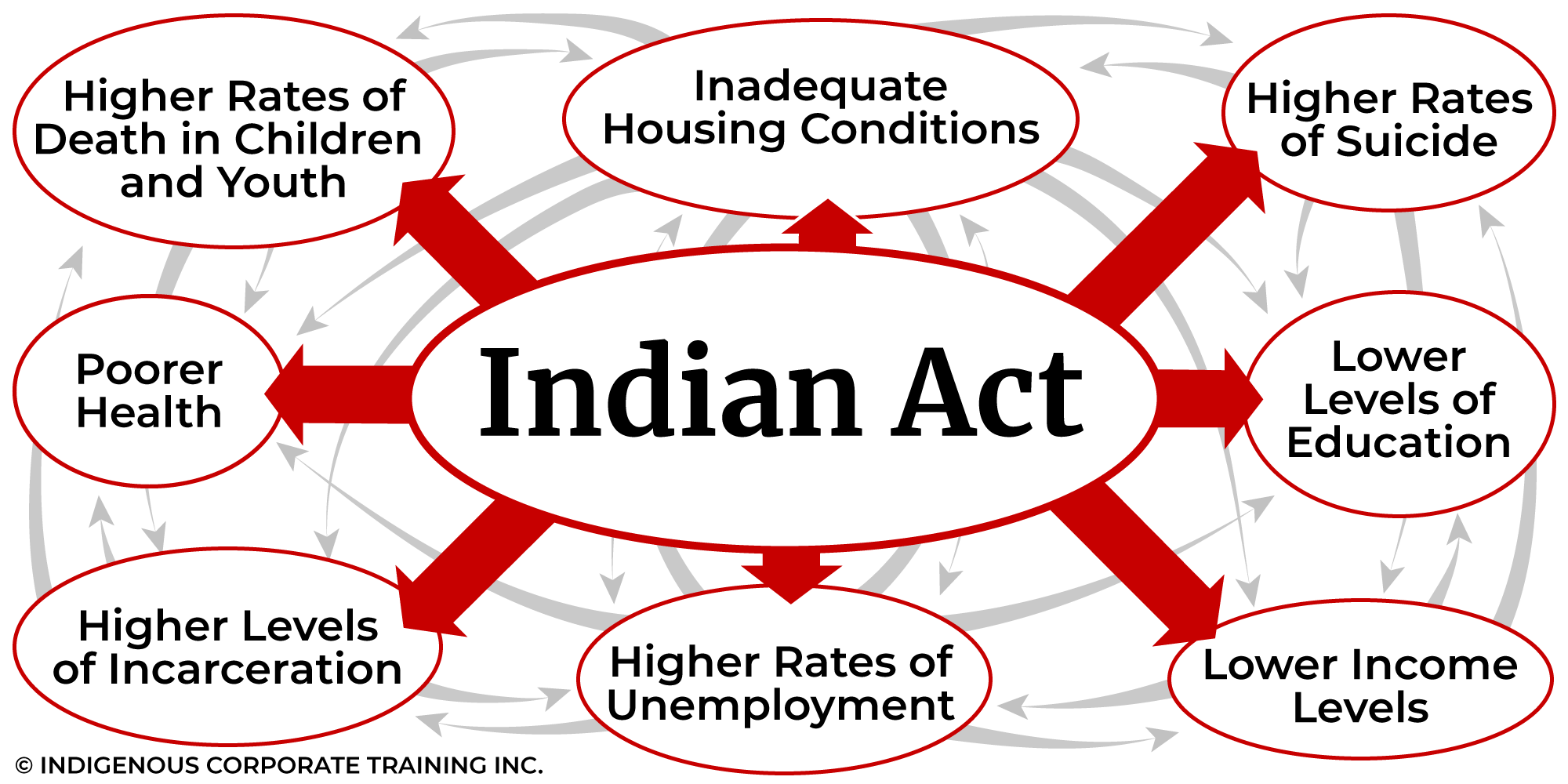

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...