Using the Inuit Perspective to Successfully Lead a School

Looking for an adventure five years ago, I travelled to a small Inuit community in Nunavut. I quickly discovered teaching Inuit children is a rich,...

In Inuit tradition, a child is not considered to be a complete person until they receive an atiq or “soul name,” usually given at birth. The construction of a subject’s identity, therefore, is a complex process involving the historical customs of “naming,” kinship practices, as well as spiritual beliefs. The subject’s identity is thus composed of multiple layers, as the following narrative suggests: No child is only a child. If I give my grandfather’s atiq to my baby daughter, she is my grandfather. I will call her ataatassiaq, grandfather. She is entitled to call me grandson. [1]

A note on terminology: In this article, we use the term “Eskimo” as it is historically accurate for the subject “Eskimo identification tags”. Eskimo is considered derogatory in Canada but is still in use in Alaska. In Canada the preference is Inuit.

Eskimos, until the 20th century, were pretty much overlooked by the rest of the world and had few interactions with Europeans apart from infrequent encounters with explorers and whalers. That all changed when fur traders began to move further north, and with them came trading posts, the RCMP, missionaries, government agencies... and bureaucracy. With the bureaucracy came the inevitable desire for lists of who was who in the vast tundra.

The new northerners had trouble pronouncing and spelling Eskimo names and couldn’t fathom the traditional naming system that was, to them, illogical. The first wave of efforts to establish a naming system was driven by the missionaries. Their plan was for the population to be baptized and given Christian names. This was quite well received but Eskimos in turn had trouble pronouncing and translating the new names into syllabic writing script so they modified their new names. They also continued to use their traditional names, which caused quite a bit of confusion for government officials, medical personnel and RCMP.

By 1929, after many years of frustration and confusion, government officials considered and introduced various ways to devise a universal system of identification. Some attempts were so very poorly planned and executed they simply exacerbated the confusion around identities. As was typical of the time, little regard was paid to the impact on Eskimos of having their “soul name” erased.

The importance of the Eskimo name is something I have spoken of before. It is very important for each individual to be properly identified. In the Eskimo tradition it had an even greater significance, and there is a persistence of the attitude derived from those traditional beliefs, whereby the name is the soul and the soul is the name. So if you misuse someone’s name, you not only damage his own personal identity in the existing society but you also damage his immortal soul. [2]

Here’s a timeline of what was suggested:

1929 - standardization of spelling of names

1932 - separate files for each Eskimo showing name in English and syllabic characters, along with fingerprints

1933 - fingerprinting by the RCMP of Eskimos who received medical assistance

1935 - binominal system of names - the head of each family to select a common name for his family

1935 - identification disc, similar to that used in the army, stamped with a letter and a number

The identification disc system was adopted in 1941. The plan was for each Eskimo to be assigned a number on a disc which was to be worn at all times or sewn into clothing. The numbers were used in all official documentation, including the salutation in letters. This identification system was fraught with issues including Eskimos destroying the discs, shortages of the discs which meant many people were not registered, and inconsistent numbering. Also, the registration records of babies born before the advent of the disc were not updated with the new numbers and many babies born after 1941 were also not registered due to the shortage of discs in certain regions. Inconsistent reporting and registering of deaths contributed to the confusion.

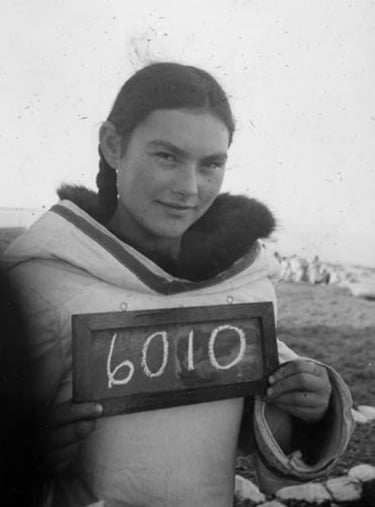

Identification became more critical in 1945 with the introduction of the Children’s Allowance program (later known as Family Allowance but currently known as Child Benefit program) - Canada’s first universal welfare program. Accurate family records were required for the issuance of the monthly payment. The existing registration system was a mess so “all discs were recalled and new ones were issued. The Canadian Arctic and Northern Quebec were divided into twelve districts, with three districts in the west (W1, W2 and W3) and nine districts in the east (E1 to E9). The new disks incorporated an alphanumeric identifier, reflecting the geographic region Inuit inhabited, as well as their unique four-digit number.” [3]

In 1968, the Northwest Territories Government (NWT) introduced “Project Surname”, an initiative intended to persuade all Eskimo adults to adopt and register a family name, which, along with their given names, was given a standardized spelling. By 1972, all Eskimos within the NWT were registered and the disc system was discontinued. The disc system was gradually phased out in other regions.

[1] Mark Nuttall, Editor, Encyclopedia of the Arctic

[2] A. Barry Roberts, Eskimo Identification and Disc Numbers, A Brief History

[3] Canada's Relationship with Inuit: A History of Policy and Program Development, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

Featured photo: Photo: J. C. Jackson / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / Library and Archives Canada / a102695-v6

Looking for an adventure five years ago, I travelled to a small Inuit community in Nunavut. I quickly discovered teaching Inuit children is a rich,...

We’ve talked about the definition of Indigenous Peoples and the constitutional significance of Indigenous or Aboriginal. In this article, we drill...

1 min read

National Indigenous Peoples History Month is a time to acknowledge the history of Indigenous relations and Indigenous Peoples in Canada....