The Enduring Nature of First Nation Stereotypes

Canada is a country whose citizens pride themselves on their diversity and promotion of pluralism yet turn a blind eye to the continued stereotypical...

The history of extinguishment of First Nation title has its roots in old or historic treaties as shown from the excerpt below from Treaty 3, between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteau Tribe of the Ojibbbeway Indians, signed on October 3, 1873. It is plain to see the language of extinguishment - “cede, release, surrender”.

The Saulteaux Tribe of the Ojibbeway Indians and all other the Indians inhabiting the district hereinafter described and defined, do hereby cede, release, surrender and yield up to the Government of the Dominion of Canada for Her Majesty the Queen and Her successors forever, all their rights, titles and privileges whatsoever, to the lands included within the following limits... [emphasis added]

There are a number of Treaties with this wording, but you would be hard-pressed to see any modern treaties with this type of language.

Treaty 3 is an example of the boilerplate treaties that were “shopped around” in the pre-Confederation era as the Crown rushed to secure the rights of what was then known as Upper Canada. During the treaty signing frenzy of the era, the colonials recorded the provisions and signed the documents with a full understanding of the provisions contained within. The First Nation “signees”, being a society that relied on oral histories, recorded their understanding of provisions and promises made in their traditional way - through stories and in wampum belts, and not with a full understanding of the immense significance of what they were signing away.

Some of these treaties were written up and signed within mere days and were very vague on critical points – such as the extent of the land in question. One infamous description of the land involved was the gunshot clause of a treaty prepared in 1787 for the Crown to acquire all the lands north of Lake Ontario, between what is today Kingston and Toronto. The wording used to describe the actual land mass was “from the lakeshore as far inland as a gunshot could be heard on a clear day.” The First Nation involved did not sign this treaty as they very sagely wanted to know whose gun, whose ears and what time of year.

In Canada, today, the Crown cannot extinguish Aboriginal title without the explicit prior informed consent of the proper Aboriginal title holders. In Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, the Court said that Aboriginal title represents an encumbrance upon the Crown’s ultimate title, and because of that the Crown needs to have prior, informed, explicit consent to extinguish Aboriginal title.

The historic Numbered Treaties involved the extinguishment of rights. Those negotiating modern treaties, especially in BC, are not so keen to cede, release, or surrender their rights, titles and privileges forever – or, in other words, extinguish their rights forever. The language you are more likely to see is “as modified by treaty” or perhaps something similar. Today’s First Nations do not have an interest in nor are they seeking to extinguish legal interests in treaties, but are modifying.

The Importance of Treaty Education provides some insight into why all Canadians should have knowledge of treaties.

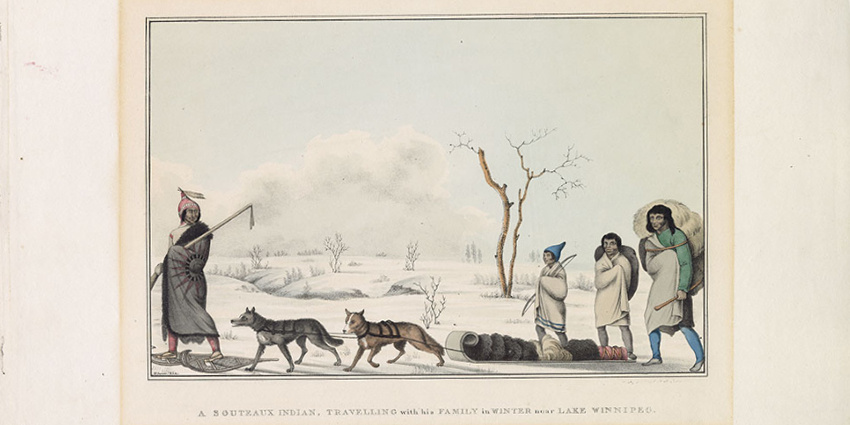

Featured photo: "A Souteaux Indian Travelling with his Family in Winter near Lake Winnipeg", lithograph, coloured by hand, 1825. Photo: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1970-188-1756 W.H. Coverdale Collection of Canadiana.

Canada is a country whose citizens pride themselves on their diversity and promotion of pluralism yet turn a blind eye to the continued stereotypical...

1 min read

The 2015 Canada Games marks a series of firsts. It is the first time in the 48-year history of the Canada Games that a First Nation has been granted...

The First Nation Health Authority (FNHA) in BC has taken over control of all Health Canada health programs and services for the 203 First Nations in...