What is the Nation Rebuilding Program?

In January 2019, a situation arose in northern BC that brought to the public’s attention the fact that some Indigenous communities have two forms of...

2 min read

Bob Joseph July 03, 2012

The role and responsibilities of First Nation Chiefs, traditional or elected, are not easily defined and are not synonymous across Canada due to the range of traditions in First Nations culture. But, without a doubt, the common struggles against the pressures of ongoing low socio-economic conditions, housing, health and education are challenges most First Nation Chiefs share.

In terms of requirements of a good and effective leader, there are some basic commonalities, as defined by Manley Begay, (Navajo), faculty chair of the Native Nations Institute at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy and Senior Lecturer in the American Indian Studies Program at the University of Arizona. In a study in 1997, Begay identified five common traits:

First, Native meanings of leader do not necessarily imply the accumulation of wealth (property and goods). Rather, there is an emphasis on position and role. Second, Native leadership terminology implies a proactive approach with the use of terms like “to direct” and “leads the people.” Third, a Native leader works with the people, rather than commanding or having power over them. Fourth, there is a recognition that leadership has male and female aspects. Fifth, the religious and spiritual aspects of leadership are important.

As with most aspects of life for First Nation People in Canada, the introduction of the Indian Act in 1876 injected a seismic shift in traditional practices. Prior to the Indian Act, nations had their own traditional governing structures and protocols; the mantle and power of First Nation Chiefs was frequently passed from one generation to another through cultural laws. With the introduction of the Indian Act, which mandated that elections must be held every two years, traditional governing structures - the very backbone of each nation - became obsolete, or at least that was the intention of the government of the day. The enforced European election process injected confusion and undermined and destroyed traditions that were as old as time itself. Some nations, however, have maintained their hereditary chief tradition so have both hereditary and elected chiefs.

Under the Indian Act, nations that had thrived and survived on their own terms pre-European contact became “bands” which are defined, in part, as a body of Indians for whose use and benefit in common, lands (reserves) have been set apart. Each band is allowed to have one elected chief and one elected councillor for every 100 band members, with a minimum of two councillors per band and no more than twelve. The elected officials are ultimately accountable to Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development, and federal policy.

As the Indian Act was created without input from First Nations people, it is not surprising that such a document would disregard the deep historical significance of traditional governing structures.

Be sure to research governing structures before meeting with a community to determine the presence of elected and/or traditional chiefs. Also, in your opening remarks be sure to acknowledge both elected or traditional leaders by name if possible.

Featured photo: Chiefs of BC nation, 1910. Photo: Library and Archives Canada/PA-095524

In January 2019, a situation arose in northern BC that brought to the public’s attention the fact that some Indigenous communities have two forms of...

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other...

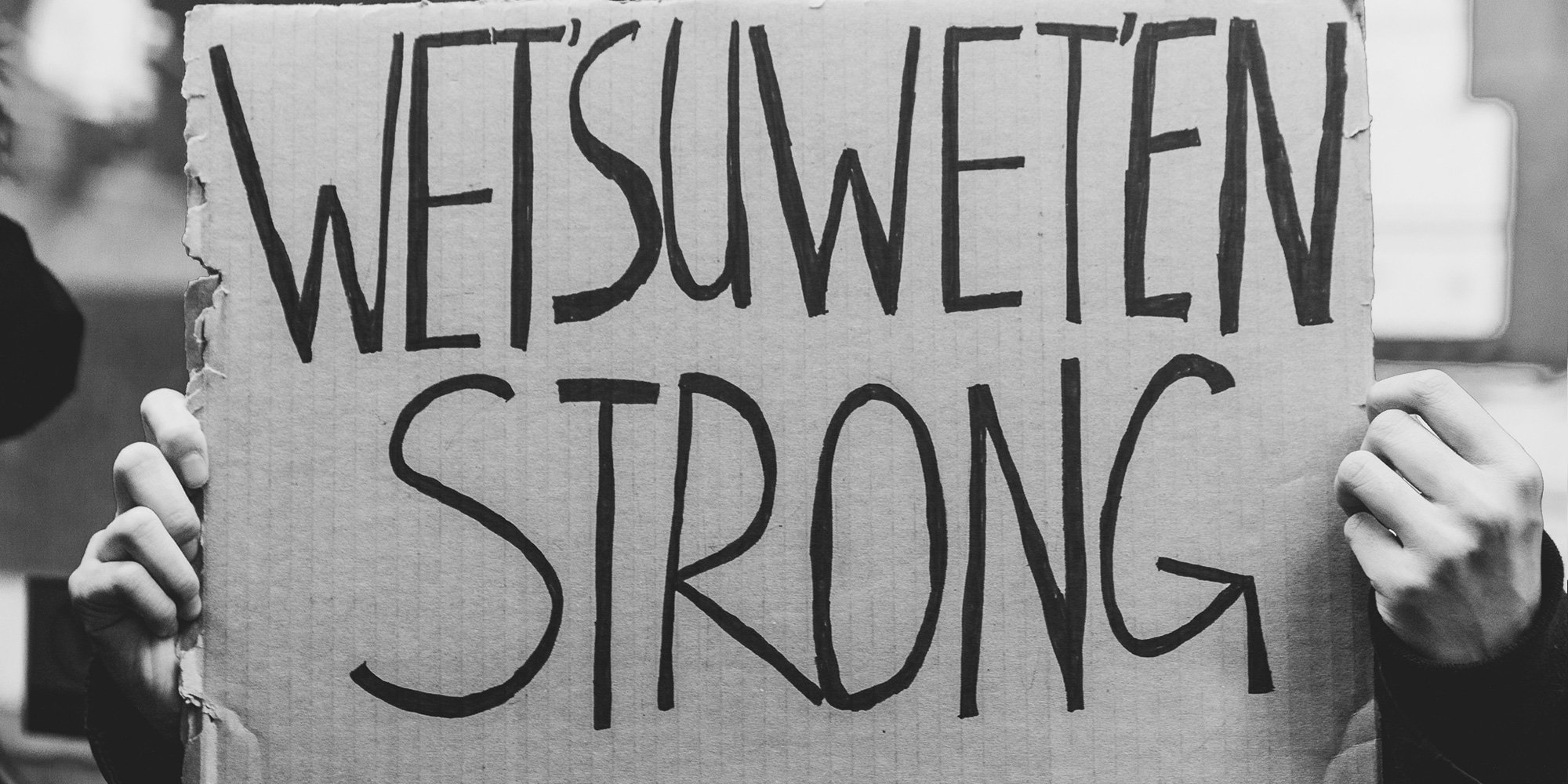

The Wetʼsuwetʼen protests in 2019 and 2020 were widely reported on and sparked public interest around one of many misconceptions of Hereditary Chiefs...