Insight on 10 Myths About Indigenous Peoples

The definition of “myth”, according to the Oxford Canadian Dictionary, is “a widely held but false notion.” When it comes to the topic of Indigenous...

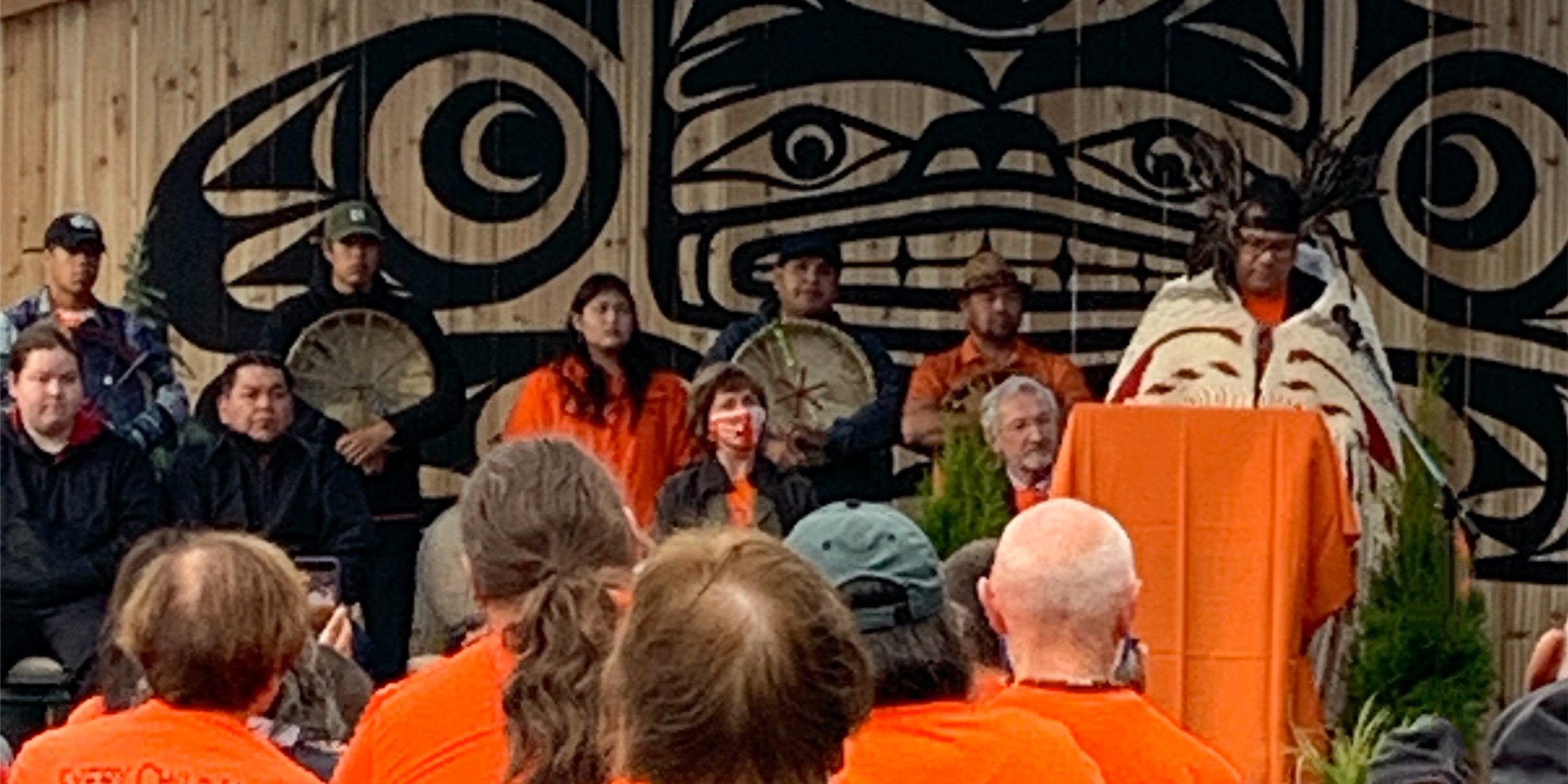

In 2015, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) released its six-volume report on residential schools it brought the details, impacts and outcomes of the schools starkly into the spotlight. Canadians were shocked to hear that the federal government enacted policies of cultural genocide as a means to achieve the ultimate goal of separating Indigenous Peoples from their lands and sovereignty. The report presented a harsh contrast to the common perspective of Canada as a benign nation shaped through the foresight of the founding fathers and the hard work of settlers.

The TRC’s report provided context for Canadians to understand the historical relationship between the federal government and Indigenous Peoples. Understanding the context is a key component for Canadians to understand why there must be reconciliation.

To the Commission, “reconciliation” is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. For that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour. [1]

Reconciliation is an immense undertaking. For some, the necessity is beyond question, and the process is straightforward. For others, the necessity is not as clear, and barriers impede the process.

Here are four common barriers to reconciliation and some suggestions for solutions. There are common elements among the solutions

Some people don’t want to accept the hard truths about Canada, the actions of the founding fathers of Confederation, the Indian Act, assimilation policies that were branded as “cultural genocide,” land seizure, and disregard/disrespect for treaties. The reality does not fit with their image of Canada as a country with a reputation for respecting human rights.

But it’s not just everyday Canadians who have trouble coming to terms with reality. This perspective was on display when Stephen Harper, one year after reading the statement of apology to residential school survivors and their families, spoke to the G20 meeting and said:

We also have no history of colonialism. So we have all the things that many people admire about the great powers but none of the things that threaten or bother them. [4]

We all share responsibility for moving this country forward on the reconciliation path because the policies of colonization that created the residential schools contributed to the country in which we are living and benefiting from.

Solution:

Indigenous awareness training is a common element in the TRC’s calls to action. If you are planning to take awareness training or are planning awareness training for your team, look for a trainer who does not play the blame game. Reconciliation is not about blame. Reaching someone who has resistance to reconciliation is not going to be achieved via guilt, shame, or aggressive anger.

If reading the entire six-volume TRC Report is too much to bite off, consider reading What We Have Learned Principles of Truth and Reconciliation.

Through much psychological research, it’s now accepted science that you must experience feelings about something if you’re to take personally meaningful action on it. And without any compelling emotion to direct your behavior—and apathy literally means “without feeling”—you just aren’t sufficiently stimulated to do much of anything. [2]

Apathy lurks as a barrier to reconciliation due to a prevailing indifference some Canadians feel about Indigenous Peoples. The absence of emotional engagement makes the intergenerational harm caused by residential schools “not their problem.” This apathy also takes the shape of “Are we done yet?” or “Why can’t they just get over it?” Reconciliation will take time.

Here’s the background to how the indifference towards Indigenous Peoples was established over time:

invisible:

The Doctrine of Discovery provided a framework for Christian explorers, in the name of their sovereign, to lay claim to territories uninhabited by Christians. If the lands were vacant, then they could be defined as “discovered” and sovereignty claimed. When Christopher Columbus arrived in North America in 1492, the Indigenous Peoples, as non-Christians, were invisible.

savages:

The founding fathers of Confederation, including our first prime minister John A. Macdonald, referred to them as “savages” in official documents.

erased:

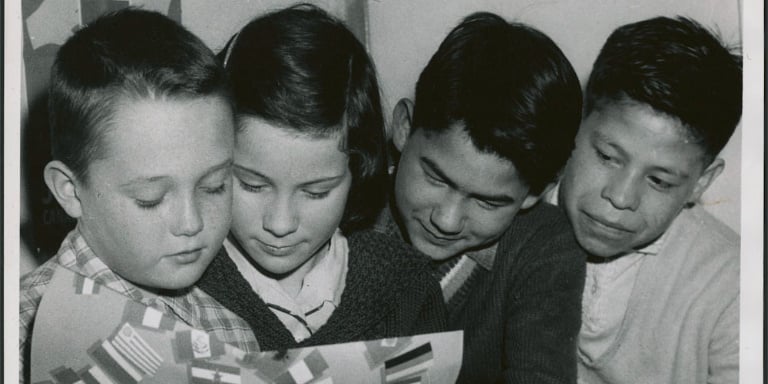

The federal government’s “objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic”.

not people:

At the midpoint of the previous century, when the Indian Act was revised in 1951, Indigenous Peoples were finally—legally—acknowledged as people. In earlier versions of the Indian Act, “The term ‘person’ means an individual other than an Indian unless the context clearly requires another construction. [3]

The experience of 150,000 Indigenous children in residential schools is part of our history. And the intergenerational impacts of poorer health, lower levels of education, employment, and income, and higher rates of incarceration and suicide are very much part of our present and will continue into our future without reconciliation. If the harm done by the residential schools is compartmentalized as “their issue” or as an “Indigenous issue” we will never achieve reconciliation.

Solution:

Education:

There are many misconceptions about Indigenous Peoples, many of which relate to the fiduciary responsibilities of the federal government as laid out in the Indian Act. Holding onto these misconceptions does not contribute to reconciliation.

The three most commonly held misconceptions are that Indigenous Peoples (specifically status Indians) get free housing, and free post-secondary education, and don’t pay taxes. People who hold these beliefs don’t see the need for reconciliation because, to them, Indigenous Peoples have it pretty good, and actually have an advantage over non-Indigenous Canadians.

Solution:

Learn about Indigenous Peoples:

Reconciliation is a daunting task. A relationship that has been dysfunctional for over 150 years is not going to be fixed overnight. Or even years. It’s going to take decades. And it’s going to take a long-term commitment on the part of all Canadians over generations.

Reconciliation is an ongoing individual and collective process and will require commitment from all those affected including First Nations, Inuit and Métis former Indian Residential School (IRS) students, their families, communities, religious entities, former school employees, government and the people of Canada. [5]

But being overwhelmed by the enormity or complexity of reconciliation is not a reason to not find some way of contributing or participating in reconciliation.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has. [6]

Solution:

Build a framework of understanding of what reconciliation is and what it is not so that you can identify opportunities that work for you.

While there remains significant work to be done, progress has been made. There have been some setbacks and there will be more along the way. But, we can’t let inertia take over when there are setbacks. It just means we have to work harder. Working towards a better Canada for our children’s children is worth the effort.

[1] TRC Final Report, Vol 6, p 3

[2] Psychology Today, The Curse of Apathy: Sources and Solutions

[3] Bob Joseph with Cynthia F. Joseph, Indigenous Relations Insights, Tips & Suggestions To Make Reconciliation A Reality, Indigenous Relations Press, 2019 p 31

[4] Stephen Harper, 2009 Group of Twenty (G20) meeting, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

[5] Indian Residential School Survivors Society

[6] Donald Keys, Earth at Omega: Passage to Planetization (Epigraph of Chapter VI: The Politics of Consciousness), Quote Page 79, Published by Branden Press, Boston, Massachusetts 1982

Featured photo: Unsplash

The definition of “myth”, according to the Oxford Canadian Dictionary, is “a widely held but false notion.” When it comes to the topic of Indigenous...

It is vital that the commitment to Truth and Reconciliation does not fade just a few weeks after the first National Day.

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...