Hereditary Chiefs vs. Elected Chiefs: What’s the Difference?

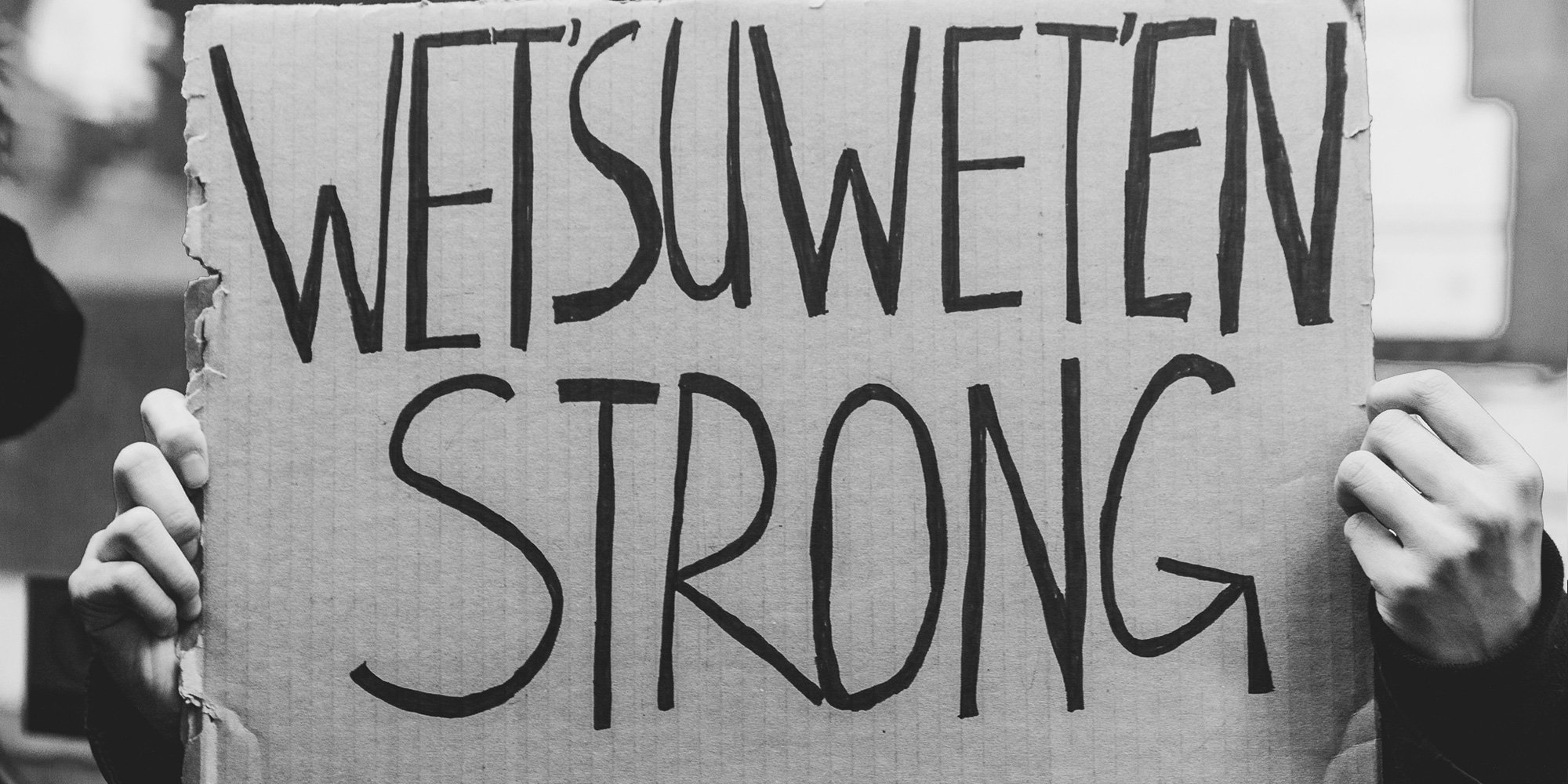

The Wetʼsuwetʼen protests in 2019 and 2020 were widely reported on and sparked public interest around one of many misconceptions of Hereditary Chiefs...

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.

Sir John A Macdonald, 1887

Long before Prime Minister John A. Macdonald made the above statement of intent, the Indigenous Peoples who had occupied the land since time immemorial had effective, traditional forms of leadership and governance. The traditional form of governance pre-contact was most commonly based on leadership by hereditary chiefs. However, it should be noted that "chief" is a European term. Traditional leaders were headmen/women, clan leaders, heads of villages, or groups of people.

Hereditary chiefs, as the name implies, are those who inherit the title and responsibilities according to the history and cultural values of their community. Their governing principles are anchored in their own cultural traditions. Hereditary chiefs carry the responsibility of ensuring the traditions, protocols, songs, and dances of the community, which have been passed down for hundreds of generations, are respected and kept alive. They are caretakers of the people and the culture. My father, Chief Dr. Bob Joseph, O.B.C., is a hereditary chief, and as his son, one day I will become a hereditary chief in accordance with strict cultural laws.

The introduction of the Indian Act in 1876 introduced the Elected Chief and Council System which forced communities to elect their leaders and to hold elections every two years. Know also that they are elected by their people but are accountable to the federal government. As you can imagine, this new form of leadership caused friction and confusion.

1. Does every First Nation in Canada have a hereditary chief?

No. In some communities, waves of smallpox and measles epidemics wiped out the entire hereditary lineage. These communities rely on elected chiefs and councils as laid out by the Indian Act.

2. How is the hereditary chief title passed to the next person?

Each community and culture has its own protocols and ceremonies. In many West Coast cultures, the title and responsibilities are passed to successive hereditary chiefs during a potlatch.

3. What happens if there isn’t someone next in line to take on the title and responsibilities?

Again, each community may have its own protocol and ceremony for passing the title along. In some communities, it can go down through the men and in others through the women. They will also have rules about the next person to inherit if there is no available or willing heir. I am aware of one culture where if the oldest nephew does not want the responsibility they can pass it to the next oldest nephew as long as it’s conducted in a public ceremony. I know in other cultural practices that if there is no son then it goes to the daughter who takes it with her as dowry to her new husband. Those are just two examples of many. Remember, there are 11 major language families, 50 different dialects, and over 600 bands in Canada. There are many, many more examples but we just wanted to give a small perspective.

4. If there is both a hereditary chief and an elected chief, which one has the final say on economic development projects?

My favourite answer that I share in my public and onsite training workshops is “It depends”. If you are working with a community that has both forms of leadership, it is something that needs to be sorted out before you go and commence work. I propose that research be undertaken before any kind of work begins. It will save you tons of time and expense for the effort. To find the information you will need to check out websites, visit cultural centres, talk to community people, talk to government people and even reach out to consultants to share their insights. Personally, I have seen situations in which the elected people have a say on development projects and other examples where it is the hereditary chiefs who have the say on development. Sometimes they get along and understand each other and other times their relationship is tense, to say the least. The common mistake here is that people assume it is the elected chief and council and that’s what gets them into trouble. Also, if this was a level 300 Indigenous Consultation and Engagement course I would tell the participants that the rights are collectively held by a group of people and that a broader group of people needs to be involved in decisions around economic development.

5. How can one community have two forms of leadership? What if the elected chief and the hereditary chief have different philosophies or views about a certain issue?

This is a great question. When the Indian Act brought elections into the communities it was an attempt to further erode age-old traditions and cultures by neutralizing the role of the traditional leader. The process of having elections, and having community (and sometimes family) members vying against one another caused, and continues to cause, a great deal of friction, particularly in smaller communities.

Calling the elected leader “chief” was another measure aimed at undermining the role of hereditary leaders. Polarizing opinions between elected and hereditary chiefs, especially in concern with granting approval for resource development projects, can be a source of friction in First Nation communities. Again, research and planning of approach are the best ways to deal with different views or philosophies.

Can a hereditary chief be elected as the elected Chief?

Yes.

Can an elected chief become a hereditary chief?

Yes.

Bob Joseph, founder and President of Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., has provided training on Indigenous relations since 1994. Each year he assists thousands of individuals and organizations in building Indigenous relations. His Canadian clients include all levels of government, Fortune 500 companies, financial institutions, including the World Bank, small and medium-sized corporate enterprises, and Indigenous Peoples. Bob is the developer of a multi-layer suite of Indigenous relations training courses and the author of the national bestseller 21 Things® You May Not Know About The Indian Act.

Featured photo: Three generations of Josephs.

The Wetʼsuwetʼen protests in 2019 and 2020 were widely reported on and sparked public interest around one of many misconceptions of Hereditary Chiefs...

The role and responsibilities of First Nation Chiefs, traditional or elected, are not easily defined and are not synonymous across Canada due to the ...

Chief Dr. Robert Joseph, O.B.C., is a hereditary chief of the Gwawaenuk First Nation who upholds a life dedicated to bridging the differences brought...