What are Gladue Reports?

Indigenous people account for less than five percent of the Canadian population, yet represent 25 percent of the total inmate population. Canada is...

The incarceration rate of Indigenous peoples in Canada should be labelled a national crisis. The flaws in the justice system are insidious and perpetuate the cycle of poverty and marginalization that is the reality for far too many Indigenous people. The situation is of such enormity that of 94 calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 18 are devoted to Justice, plus another three aimed at Equity in the Legal System - more than double those committed to any other issue.

The above statistics are not unique to the era - the incarceration rates of Indigenous people have been disproportionally high for decades. Measures have been taken from changes to Criminal Code to Supreme Court of Canada rulings, but nothing has changed. The incarceration rates keep climbing. Since 1989, eleven Royal Commissions or Commissions of Inquiry have addressed the issue of Indigenous justice either directly or as one among many questions regarding Indigenous people in Canada.

Looking at the early days of the penitentiary system, which began with the 1834 Penitentiary Act, one of its goals was to reform inmates into industrial workers through “solitary imprisonment, accompanied by well-regulated labour and religious instruction.” [1] The prison chaplains had a high authority level and acted as teachers. Following sentencing, inmates entered an imposing building where they were searched, their belongings seized, their hair cut short, and their clothing burned - effectively severing links to their former lives. Sound familiar?

Prisons and residential schools were two sides of the same coin. Two federal institutions with the same goal, albeit one less directly focused on Indigenous people - to divest Indigenous people of their connection to their land, history and culture; through assimilation to “do away with the Indian problem.”

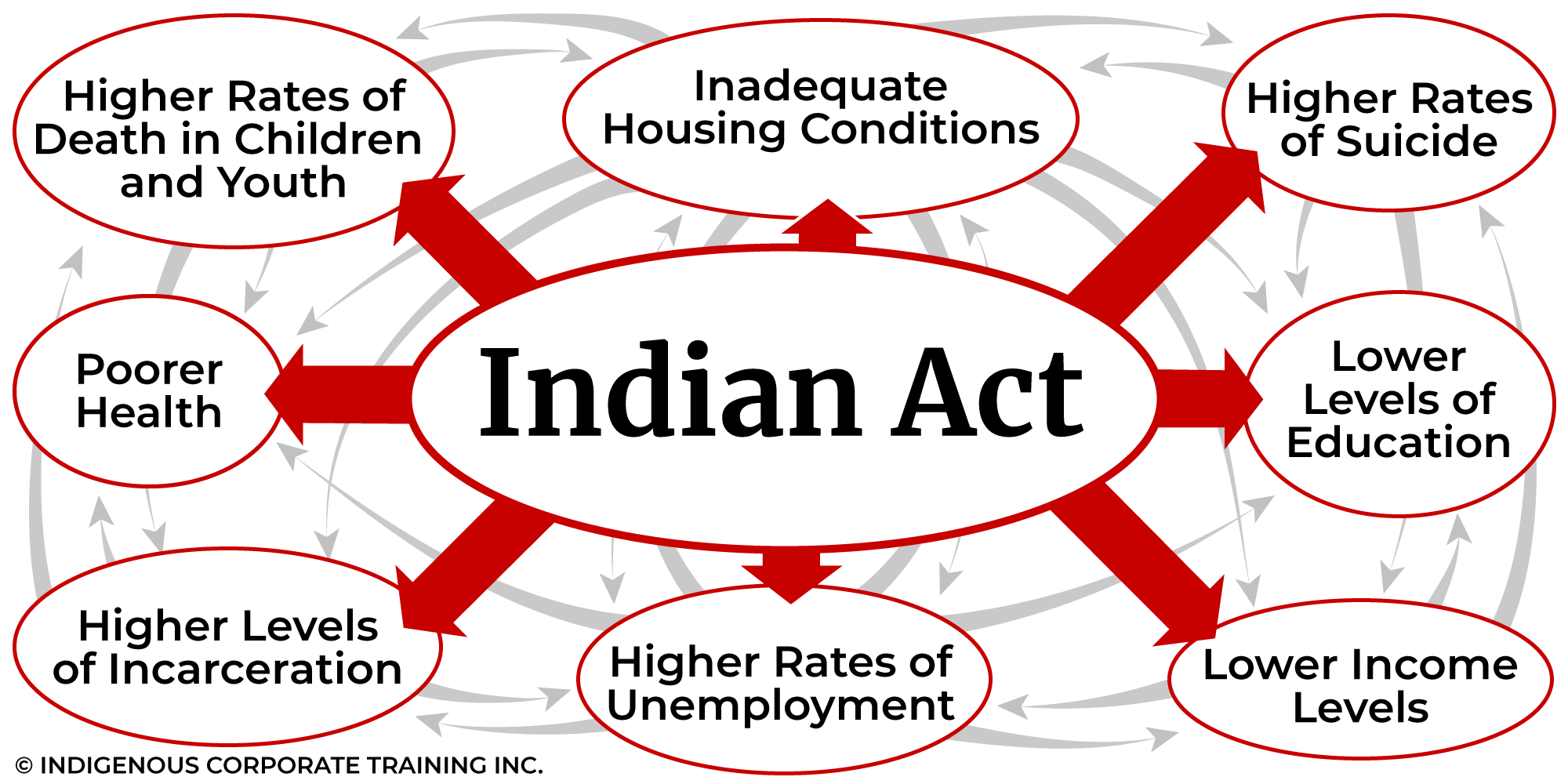

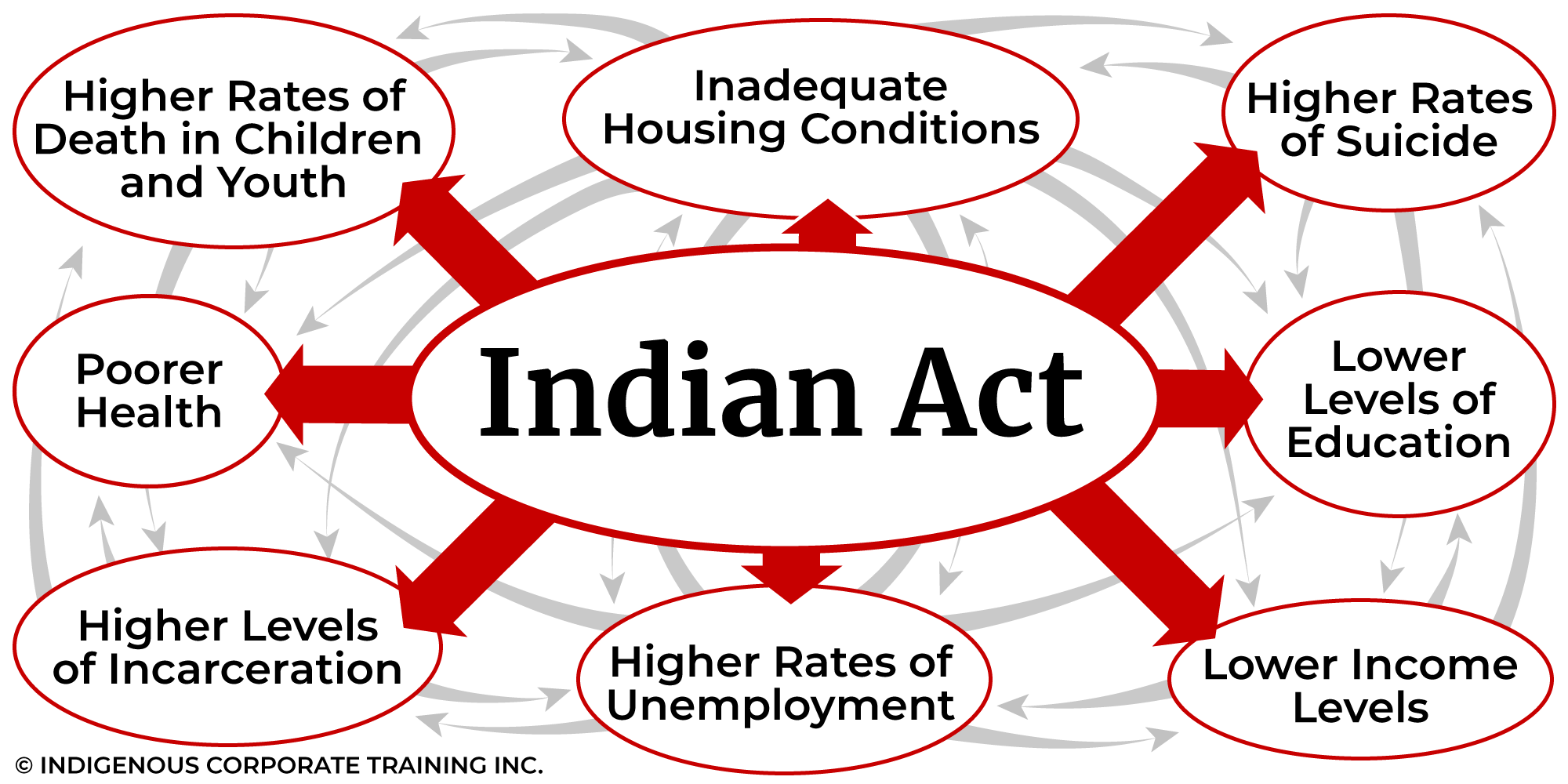

The passing of the Indian Act in 1876 put Indigenous people on a path of increasing intersections with the law. Under the repressive measures of the Indan Act, overtime, it was an offence for an Indigenous person:

Despite decades of legislative and policy efforts to address systemic racism and misogyny in the criminal legal system, the overrepresentation of Indigenous women in federal prisons has continued to skyrocket. As of May 6, 2022, Indigenous women account for half of all women in federal prisons, yet represent fewer than 4% of women in Canada. [2]

The “Injustices and Miscarriages of Justice Experienced by 12 Indigenous Women” report lists ten systematic factors leading to miscarriages of justice for Indigenous women:

The over-representation of Indigenous women in higher security levels has been a concern for decades. The Office of the Correctional Investigator's 2021-2022 Annual Report highlights the ongoing high percentage (65%) of Indigenous women classified as maximum security. The Auditor also points his finger at the reason:

A deeper dive into the situation uncovers that this over-representation is largely the result of systemic bias and racism, including discriminatory risk assessment tools, ineffective case management, and bureaucratic delay and inertia.

Residential schools were the tool the federal government used to effectively separate students (150,000 over the 150+ years the schools were in operation) from their culture, spirituality, community and family. The outcome was the majority of those who survived (over 6,000 died or disappeared) were culturally rudderless. The loss of culture continues to impact the families of residential school survivors. When Indigenous offenders enter the prison system, they are introduced to prison culture where violence solves problems. And when they are released, they take that toxic prison culture back to their communities.

For some residential school survivors whose trauma is so overwhelming, building a life outside an institution is not feasible. They commit crimes to be incarcerated because at least they will have food and a bed in a warm building. Indigenous youth have also been known to commit crimes on a Friday afternoon so that they can spend the weekend with access to food and a safe bed away from family violence.

Federal restorative programs have primarily focused on rehabilitation after sentencing; however, in 2022, the federal government launched the “Federal Framework to Reduce Recidivism,” designed to break the cycle of reoffending, support rehabilitation, and make the communities safer for everyone. The Framework was created following the royal assent of Bill C-228, or the Reduction of Recidivism Framework Act, in June 2021. The five priority areas identified to assist offenders are housing; education; employment; health; and positive support networks.

Coincidentally, we have identified four of those five priorities in our article, 8 Key Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada; follow the links for deeper dives into each issue.

The Framework, while well-intentioned, is treating the symptoms, not the underlying disease, which is a justice system rooted in colonialism. A more holistic approach is required, and that means a return to self-government, self-determination and self-reliance.

The TRC’s calls to action for reconciliation are the guidelines for all of us to follow if we are going to support intergenerational healing and de-escalate the rate of Indigenous people in the justice system.

For further learning, our Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® training has helped thousands of individuals and organizations better understand Indigenous history, culture and how the Indian Act affects Indigenous Peoples today.

[1] Adema, Seth, "More than Stone and Iron: Indigenous History and Incarceration in Canada, 1834-1996" (2016). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive).

[2] Injustices and Miscarriages of Justice Experienced by 12 Indigenous Women

Featured photo: Kingston Penitentiary, Kingston, Canada. Photo: Unsplash

Indigenous people account for less than five percent of the Canadian population, yet represent 25 percent of the total inmate population. Canada is...

1 min read

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...

In nearly every country with an Indigenous population, and that includes some of the wealthiest countries in the world, there are disparities between...