Higher Rates of Death in Children and Youth - #7 of 8 Key Issues

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death in Canadian Indigenous children and youth, occurring at rates three to four times the national...

The suicide rate among First Nations people was three times higher than in non-Indigenous populations between 2011 and 2016 in Canada. Among First Nations people living on-reserve, the suicide rate was about twice as high as that among those living off-reserve. The suicide rate among self-identifying Métis was approximately twice as high as the rate among non-Indigenous people. Among Inuit, the rate was approximately nine times higher than the non-Indigenous rate. Suicide rates were highest for youth and young adults aged 15 to 24 years old among First Nations men and Inuit men and women. [1]

A note of caution: the topic of suicide in any demographic can be emotionally disturbing. Our goal in writing about the higher rates of suicide amongst Indigenous people is to inform and hopefully generate empathy and understanding, not blame or guilt. Awareness of the key issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada, of which suicide is one of the most distressing, is part of the learning journey as Canada and Canadians move along the reconciliation path.

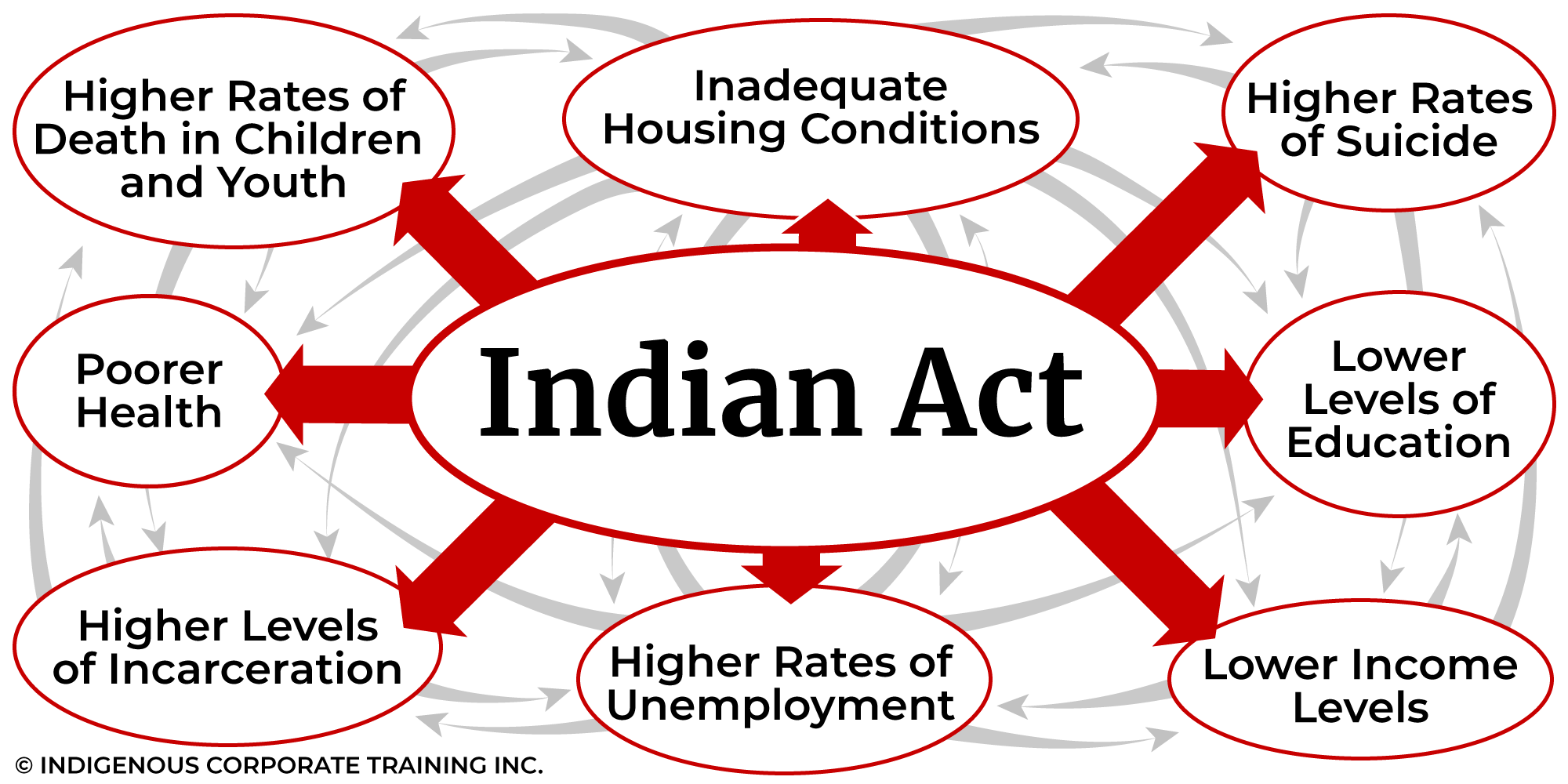

The complexity of the factors that drive Indigenous youth and adults to take their own lives relates to colonialism and the assimilation policies of the Indian Act. The deep shadow of residential schools, arguably the most devastating of all the assimilation policies, continues to shroud survivors and their families with despair and socio-economic inequalities.

In smaller Indigenous communities in which many people are related, the loss, grief and mourning from a life lost to suicide resonate throughout the community. When a family member or someone from their peer group takes their own life, those already dealing with depression, despair, anxiety, hopelessness and powerlessness may be triggered to consider suicide themselves. In some communities, there is a significant concern that one life lost to suicide will lead to a cluster of suicides.

There is a concern around quoting “rates” of suicide amongst Indigenous people because that approach lends itself to promoting the concept that suicide is a “pan-Indigenous” issue. Not every community struggles with suicide.

In a study of Indigenous communities in B.C., it was found that there was a low rate of suicide in those with higher levels of “cultural continuity factors” such as self-governance, land claims, education, health care, cultural facilities, and police and fire service had lower rates of youth suicide compared to those with fewer of these factors. The study also found that communities with fewer children in care and in which women form the majority within local government generally had a lower incidence of suicide. [2]

Building on the findings above, the work communities do to regain the three “selfs” is critical:

Long before European contact, Indigenous Peoples had their own established political systems and institutions – they were self-governing. Regaining the right to govern themselves and preserve their cultural identities is considered foundational to nation-building.

Self-reliant communities will regain their dignity and independence, incentivize children and youth to stay in school and pursue careers, improve relationships with non-First Nations, break down stereotypes, and contribute to the municipal, provincial and federal economies.

Self-determination is codified by Article 3 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDec), which states,

Article 3.

Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right, they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

The revitalization of culture is essential for a community to heal from the trauma of the assimilation policies. And an important element of cultural revitalization is language revitalization because language helps young people connect with their culture and community.

However, Indigenous languages are in a steep decline. According to UNESCO, 75 percent of Canada’s Indigenous languages are endangered, with some being only spoken by a handful of Elders. When a language dies, so does the link to the cultural and historical past. Without that crucial connection to their linguistic and cultural history, youth grow up without a sense of identity and belonging.

Indigenous communities are heterogeneous; no two are exactly alike. Therefore any intervention strategies, policies or programs that are "one size fits all" will not succeed. What a community struggling with suicide in Ontario needs in terms of support is quite different from what an Inuit community in the north needs. Taking a broad approach to prevention policies is not the answer. Effective intervention programs should be developed with input from community leaders and Elders.

In 1995, The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1995) published Choosing Life: Special Report on Suicide Among Aboriginal People, which includes thirteen recommendations. Here are their recommendations for how effective suicide prevention plans and programs should be structured:

7.

That plans and programs to prevent Aboriginal suicide through crisis management and community development be guided by the following criteria:

7.1 Initiatives must be community-driven, community-designed and accountable to local communities, regardless of the extent to which outside expertise is involved.

7.2 Initiatives must be holistic in design, addressing the physical, social, emotional and spiritual needs of Aboriginal people in the context of their family and community relationships, in ways that build self-confidence and self-respect.

7.3 Initiatives must be situated in a broad, problem-solving approach that addresses the underlying causes and changes the conditions contributing to suicide and self-destructive behaviour.

7.4 Initiatives must balance direct crisis management with efforts to strengthen families and enhance the capacities of communities to protect and support their members.

7.5 Initiatives must set a priority on ensuring that children have a safe, nurturing environment in which to develop and that youth have an opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to identifying and solving their own problems.

7.6 Initiatives must give priority to the education and training of Aboriginal caregivers in the most effective methods of preventing suicide and selfinjury and to building support networks to assist them in meeting their responsibilities.

7.7 Initiatives must encourage whole-community involvement in suicide and self-injury prevention through public education and participatory approaches to community problem solving.

It’s been estimated that between 2016 and 2026, 350,000 Indigenous youth will turn 15. In view of the fact that the vulnerable years of young adulthood are when suicide is most frequent, there is the potential for a future increase in the number of suicides. We need to keep these young people from falling into an abyss so dark and hopeless they believe that death is the only escape option available to them.

[1] Statistics Canada

[2] (Chandler & Lalonde, (1998). International Journal of Indigenous Health, December, Volume 13, Issue2, 2018, Page 18

Featured photo: Unsplash

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death in Canadian Indigenous children and youth, occurring at rates three to four times the national...

This very compelling video Stay With Us Young Warriors, We Need You Here by Vincent Schilling, a Mohawk journalist and author, is a resource we can...

1 min read

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...