The Indian Act & the Politics of Exclusion

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

Long before the arrival of Europeans, confederation, and the imposition of the Indian Act, Indigenous communities were self-determining. They decided who their people were based on cultural protocols, clan and kinship systems, and family structures, among other considerations.

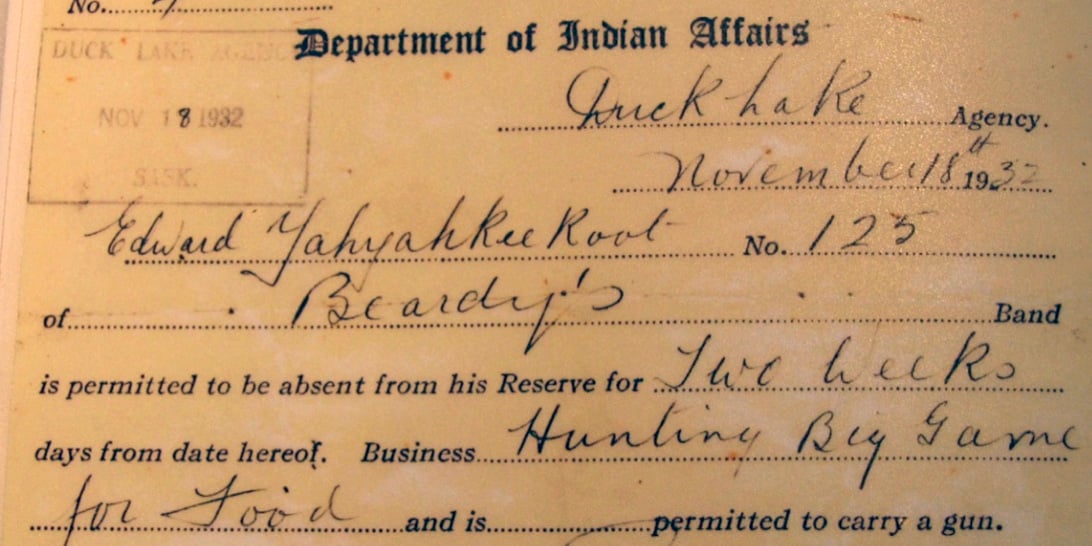

When the Indian Act was first issued in 1876, its laws were relatively benign, but the federal government began to tighten control when assimilation did not proceed as anticipated. By the late 1940s, the federal government exercised formidable control over the lives of Indigenous Peoples.

In 1951, the Indian Act underwent a significant revision. Some of the more stringent rules were repealed, while others, such as the criteria for status, were tightened. A centralized Indian Register was created to determine who was legally considered an “Indian” and, therefore, worthy of status. Being a registered or status Indian became synonymous with band membership and the right to live on reserve. Those without status were forced to leave their families and communities and live elsewhere without support.

In 1985, following the passage of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the federal government removed some of the Indian Act's more discriminatory policies.

The changes included giving bands the option to decide who belonged to the band and, by extension, who had the right to live on reserve, vote in band elections and participate in band activities, among other rights.

What greater intrusion can there be than the arrogance of assuming the right to tell another people of another culture and tradition who is and who is not a member of their community and who can and cannot live on their Lands.

David Crombie, Minister of Indian Affairs, 1985 [1]

Bands that choose to enact their own membership or citizenship codes must do so according to procedures set out in the Indian Act.

As we showed in The Indian Act & The Politics of Exclusion, considerations (political and financial) other than traditional values impacted how membership was decided. In some situations, the membership codes forced more people from the reserves, breaking up families and ties to culture, ceremony and access to ancestral lands.

Others, however, take a more inclusive approach that brings home their people who were formerly forced off reserve. These bands do not rely on descent rules but include criteria such as:

- Demonstrated knowledge of the nation’s language

- Demonstrated knowledge of the nation’s customs and traditions

- Length of residence among the nation

- Social and cultural ties to the nation

- Support from a majority of electors voting by secret ballot on the application

- Existence of close family ties within the nation

- Is self-supporting or, alternatively, can make a valuable contribution to the band, or is a caring parent who can participate in the betterment of the reserve

- A native or non-native adopted child of a person eligible to be a band member [2]

Other codes are written based on traditional protocols, family, kinship, and a belief that people, land, and the environment define belonging. An example is the Fort William First Nation’s Renewal, Resurgence, Re-Membering citizenship document that defines belonging as the relationship to each other, the land, animal, and plant nations:

It’s important to note that some bands chose to use “membership,” whereas others chose “citizenship.” There’s a small but mighty distinction between the two. “Membership” is Indian Act terminology. For many communities, “citizenship” is the word of choice.

...we have decided to speak about band membership in terms of “citizenship,” because citizenship is about giving back to your community as much as taking from it. Band membership, on the other hand, is similar to being a member of a “club,” where you expect to receive things with little reciprocity. We are not members of a club; we are citizens of Anishinaabeg nation. [3]

Additionally, “citizenship” conveys the message that relations between Indigenous communities and Canada should be conducted on a nation-to-nation basis rather than as a relationship of state and subjects.

If you would like to learn more about Indigenous culture and relations, our recommended starting point is the Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® course. It's available in Self-Guided, Live-Guided, and In-Person training platforms.

[1] As quoted in “Reclaiming Our Identity: Band Membership, Citizenship and the Inherent Right, National Centre for First Nations Governance

[2] Cornet, Wendy, "Indian Status, Band Membership, First Nation Citizenship, Kinship, Gender, and Race: Reconsidering the Role of Federal Law" (2007). Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi). 92.

[3] Fort William First Nation Citizenship Code

Featured photo: Unsplash

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

We identify ourselves in many ways - by gender, generation, ethnicity, culture, religion, profession/employment, nationality, locality, language,...

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other...