Indigenous Elder Definition

In this article, we provide the definition of Indigenous Elder and answer some specific questions people ask us in our Working Effectively with...

This is the second in a three-part series on repatriation – why it is necessary, the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and museums, and the pioneering experiences of Andy Wilson and the Haida Repatriation Committee.

Where and how does a community begin the process of repatriation? How do they find out which museums have their ancestral remains and artifacts when Indigenous remains and cultural icons were removed from villages and grave sites and dispersed throughout the world? If a museum is unwilling to repatriate, what legal recourse do communities have?

In the mid-1990s, when the Haida began the campaign to bring home their ancestors they faced a daunting task. The Haida Gwaii Museum and the Haida Heritage Resources began compiling a directory of museums worldwide, hiring summer students to write a letter to every single museum asking if there were the remains of Haida ancestors within their facility, and also compiled inventories of Haida cultural treasures held in each institution. They found, to their amazement, that their ancestors were in museums in New York, Chicago, Quebec, Oregon, Great Britain, and in BC the Royal BC Museum and the UBC Laboratory of Archaeology; during the media coverage of the repatriation campaign of the Haida Nation, private people also contacted them to return remains. Andy Wilson, co-founder, and former co-chair of the Skidegate Repatriation Committee and Haida Repatriation Committee says “Finding the museums that had our ancestors was just the first step in a huge learning curve and the beginning of a process that lasted ten years. In those ten years, we brought home the remains of over 460 of our ancestors.”

The first repatriation undertaken was from the Royal British Columbia Museum in 1998, bringing home the remains of seven ancestors (another 12 came home in 2000). The second was from the UBC Laboratory of Archaeology and involved bringing home the remains of six ancestors. Initially, requests to repatriate their ancestors were not well received. Wilson says “Museums, in general, were not all that willing to work with us until we made it clear that we weren’t going to empty their warehouses of their collections, that we were only interested in our ancestors, that we weren’t going to embarrass them by blaming them for what had happened in front of the media or make them pay.” Despite the learning curve, and the initial wariness and unwillingness on the part of the museum, the repatriation unfolded relatively smoothly, and to this day the relationships developed between the Haida and the institutions continue to grow.

The watershed moment for Indigenous repatriation in Canada was the Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples exhibit at the Glenbow Museum during the Calgary 1988 Winter Olympics. The exhibit drew international attention when the Lubicon Lake Cree staged a protest over the fact that the sponsor of the exhibit, Shell Canada, which was and continues to be today, embroiled in a land claims dispute with the Lubicon. The protest grew into a boycott which drew support from other Nations and groups who took issue over the way in which museums represented their cultures as archaic, static and no longer evolving. It also shone the light on why it was that museums assumed the right to exhibit precious cultural artifacts that had been obtained by ill-gotten means and to interpret and represent Indigenous culture.

This boycott and media attention spawned the creation of a Task Force, a joint effort between the Canadian Museum Association and the Assembly of First Nations to develop guidelines for repatriation, cultural interpretation and the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and museums. The ensuing report Turning the Page: Forging New Partnerships Between Museums and First Peoples 1992 laid out an ethical framework and strategies for Indigenous Peoples and cultural institutions to work together.

While it sounds very positive and promising that a Task Force was struck and did make recommendations, in reality, few Indigenous communities are aware of the Task Force report. Unlike museums in the United States which, under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, are required by law to repatriate ancestral remains and artifacts if requested or face substantial fines, there is no equivalent law or act in Canada.

Wilson says, “Most museums in Canada now will work with First Nations to repatriate as long as they know they aren’t going after the artifacts. We are only at the first phase of repatriation which was to bring home all known human remains from universities and museums around the world. The second part is to bring back the artifacts.” This second phase has already begun but it too will be a long, exhaustive process, will be costly, and will require Indigenous communities to form committed and focused committees to work through the process.

Please contact Andy Wilson for permission to reuse his comments. Mr. Wilson can be reached at andywilson5612@gmail.com

*All private repatriations are treated as anonymous unless otherwise specified

Consider taking one of our Indigenous cultural awareness courses to learn about the background on death, disease and depopulation of Indigenous communities following contact with Europeans.

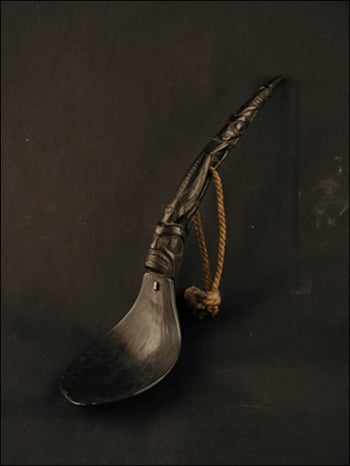

Featured photo: Flickr, Thomas Quine

In this article, we provide the definition of Indigenous Elder and answer some specific questions people ask us in our Working Effectively with...

This is the third article in a three-part series on Indigenous repatriation – why it is necessary, the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and...

Indigenous awareness is a broad term – I know because my onsite and public workshops are dedicated to helping people understand the full extent of...