ABCs of Indigenous Awareness

We have over 700 articles on our blog so decided to see if we could put the blog to the test by having an article that applied to every letter of the...

Little Indian kids on a bridge up in Canada

They can balance and they can climb

Like their fathers before them

They’ll walk the girders of the Manhattan skyline

Song for Sharon by Joni Mitchell

For over a hundred years, First Nation steel workers from Canada have applied their infinite skill and daunting bravery to the famous skyline of New York City. Generations of these men, known as “skywalkers”, have balanced precariously far above the city to “work high steel” on the city’s iconic buildings.

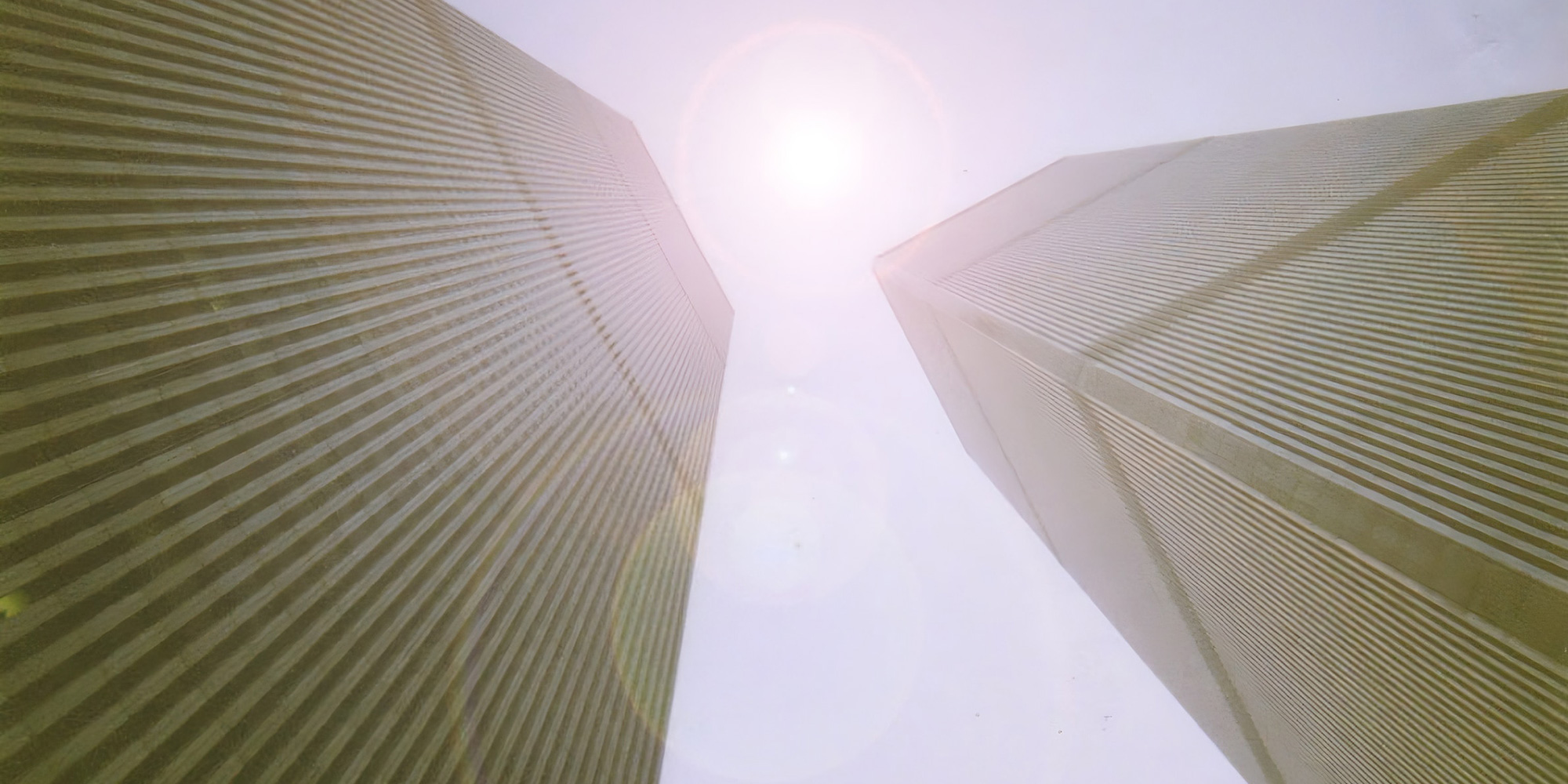

There is a particular First Nation steel worker legacy woven into the tragic saga of the Twin Towers - they were there to build the World Trade Center Towers (110 stories high; construction began in August of 1966; North Tower completed December 1970; South Tower completed, July 1971). They were there in September 2011 to clean up the tragic, tangled mess of what their forefathers had helped to build, and they were there in May 2013 to put in the final rivets of the 124-metre spire atop the One World Trade Center built to replace the Twin Towers.

While many First Nations have proud histories of highly skilled steel workers working on major projects in Canada and the United States, this article is dedicated to the Mohawks of Kahnawake.

The Kahnawake steel worker tradition dates back to 1886 - CP Rail wanted to build a cantilever bridge across the St. Lawrence from the village of Lachine on the north shore of the river to a point just below the Kahnawake village on the south shore. In exchange for permission to build the bridge abutment on the Mohawks' reservation land, CP Rail and the bridge general contractor, Dominion Bridge Company, promised the Mohawks of Kahnawake day labour jobs. The Mohawk workers were far more interested in working on the bridge than they were in unloading materials for the bridge. The foremen noticed the agility, grace, and apparent disregard of heights of the men when they were walking on bridge spans.

In the preface to “Apologies to the Iroquois” (1949), Joseph Mitchell quotes an official with the Dominion Bridge Company:

They would climb up into the spans and walk around up there as cool and collected as the toughest of our riveters... They seemed immune to the noise of the riveting, which goes right through you and is often enough in itself to make newcomers to construction feel sick and dizzy [1]

The men were particularly interested in riveting – the most hazardous and highest-paying aspect of steel structure erection – and soon there was a solid core of Kahnawake riveters working on the bridge.

Following that project, which took two years, the Kahnawake riveters moved on to work on the “Soo Bridge” that connects Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. They began training their own gangs of workers, and by 1907, over seventy members of the Kahnawake First Nation were experienced bridge workers.

In August 1907, during the construction of the Quebec Bridge which crossed the St. Lawrence, a span collapsed and 96 men were killed – 35 of whom were from Kahnawake – a devastating blow to the community. Their graves are marked with crosses made of lengths of steel girders. The loss of these men cut a deep swath through the community but rather than deter young men from wanting to go into high steel work, it inspired them. The women, knowing they could not turn this tide, wisely rallied and forced the remaining bridge gangs to split up so they were not all working on one job at the same time - "booming out". The gangs spread out and soon were working on many different high-steel projects in Canada. By the 1920s, they began travelling to New York City to work on projects there (under the 1794 Jay Treaty, Aboriginal people born in Canada were allowed to work in the United States). Their reputation quickly grew, and soon the legendary Kahnawake Skywalkers were working on all the major projects in New York City including the George Washington Bridge and Empire State Building.

The tradition of Kahnawake steel workers, men and more recently women, travelling to work in New York each week continues to this day – it is estimated that approximately 200 make the weekly trip.

[1] Edmund Wilson, Apologies to the Iroquois with a Study of The Mohawks in High Steel by Joseph Mitchell, Syracruse University Press, 1992, p. 14

Featured photo: Unsplash

We have over 700 articles on our blog so decided to see if we could put the blog to the test by having an article that applied to every letter of the...

As June 5 is Canadian Forces Day we thought it would be timely to provide some history of Aboriginal enlistment in the Canadian Forces (CF) and why...

The Bank of Canada put out a call for nominations of Canadian women for a series of new banknotes. This is not the first time women have been...