1 min read

8 Key Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...

3 min read

Bob Joseph April 04, 2023

Indigenous Canadians earn about 70 cents for every dollar made by non-Indigenous Canadians, according to Canada's income data. This is a very frequent occurrence in metropolitan areas, where Indigenous employees earn 34% less than non-Indigenous workers doing the same job. The situation is much worse in remote reservations* where non-Indigenous individuals earn up to 88 percent more than Indigenous people. [1]

*Please note in Canada, we use "reserves", but as this is a quote, we have left it as is.

The 2021 Census marked the first time low-income data was made available for all geographic regions in Canada, including reserves and northern areas. Of the 1.8 million Indigenous people in Canada in 2021, 18.8% lived in a low-income household, as defined using the low-income measure, after tax, compared with 10.7% of the non-Indigenous population. Nearly one-quarter (24.6%) of Indigenous children aged 14 years and younger lived in a low-income household in 2021, more than double the rate among non-Indigenous children (11.1%).

A household is considered low income if its income is below 50% of the median household income; the annual average household income was a little over $75,452 in 2022. [2]

In the provinces, the poverty rate for Indigenous people (excluding First Nations people living on reserve) fell from 23.8% in 2015 to 11.8% in 2020. Specifically, the rate was 14.1% among First Nations people living off reserve, 9.2% among Métis and 10.2% among Inuit in the provinces. The corresponding rate for the non-Indigenous population in the provinces in 2020 was 7.9%." [3] Please note that the pandemic relief benefits were an essential component of income in 2020 and are considered a factor in the decrease in Indigenous people living below the poverty line. Poverty is often assessed by measuring the number of Canadians with low incomes.

As you can see, the poverty rate for First Nations people living off-reserve is nearly double that of non-Indigenous people. The federal government does not collect data on the poverty rate in on-reserve households for various reasons. But, based on available statistics on education attainments and rate of employment, it can be surmised that the poverty rate is higher for those living on reserve.

The Government of Canada defines poverty as:

The condition of a person who is deprived of the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society. [4]

The federal government bases its definition on financial metrics, however, for Indigenous Peoples, it should include cultural perspectives on poverty.

Some Indigenous languages do not have a word for poverty, according to the First Nations Perspectives on Poverty report. Many Elders and adults interviewed for the report had a more holistic view of what made a person poor. There was a common sentiment that one may be materially wealthy but culturally poor.

I don’t equate wealth to money, and richness to money… [T]o be well-off, I think it’s human characteristics: Do you have your language? Do you follow your culture? Do you do your ceremonies? Those things are incredible indicators for us. The only thing that we’re given to measure everything else on wealth is measured …from the outside, so those are my measurement tools.

Gordon Peters, Eelūnaapèewii Lahkèewiit, Ontario

Before the arrival of Europeans in 1492, there was no “poverty” because of the collective commitment and responsibility to the community, looking out for each other, managing and sharing resources, and trading with other communities. The priorities were culture, family, identity and living in harmony with the natural world. The fur trade introduced a fundamental shift from the “bush economy” (hunter/gatherers, agrarian and fishers) to a wage economy and dependency on external markets.

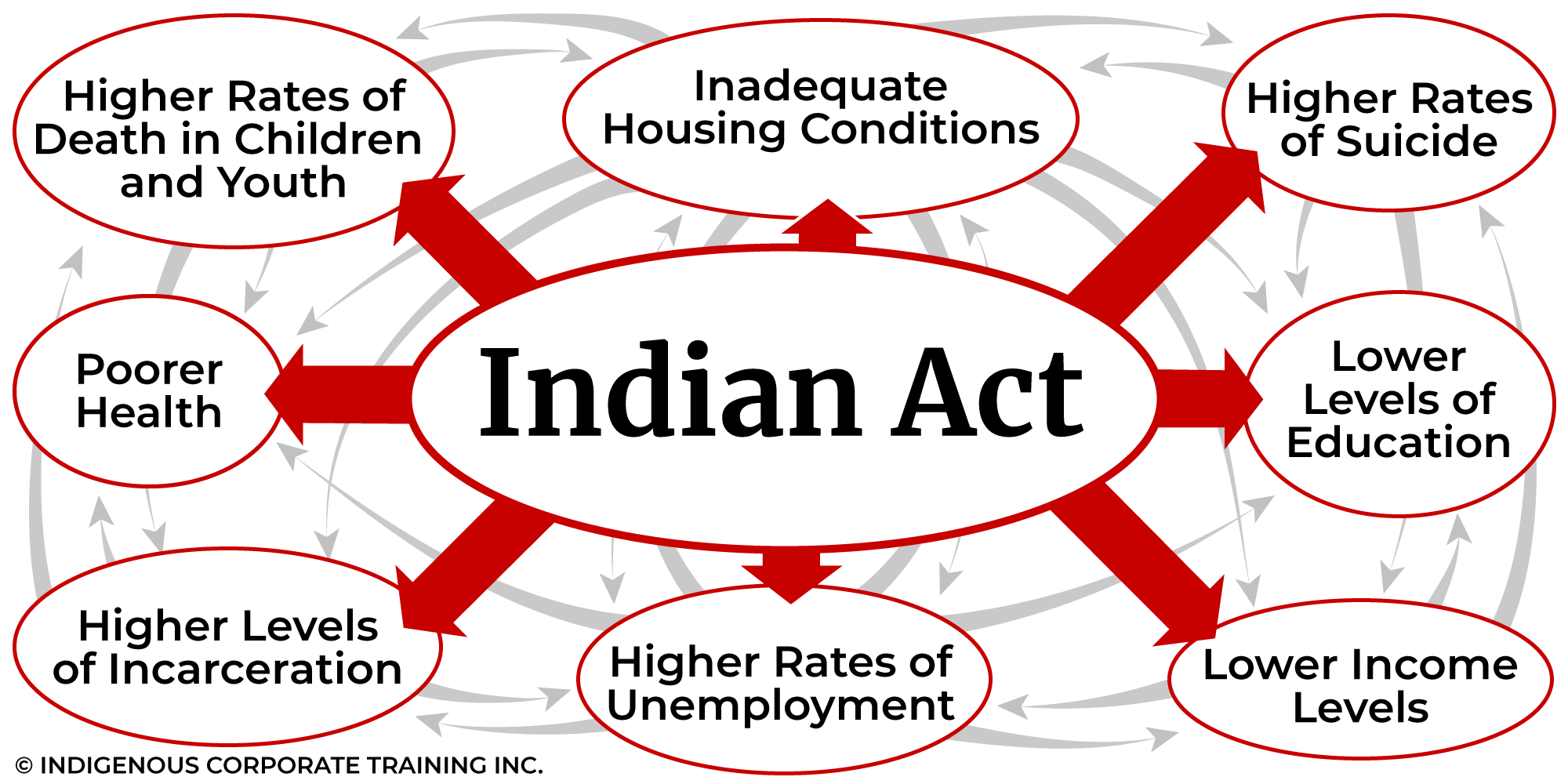

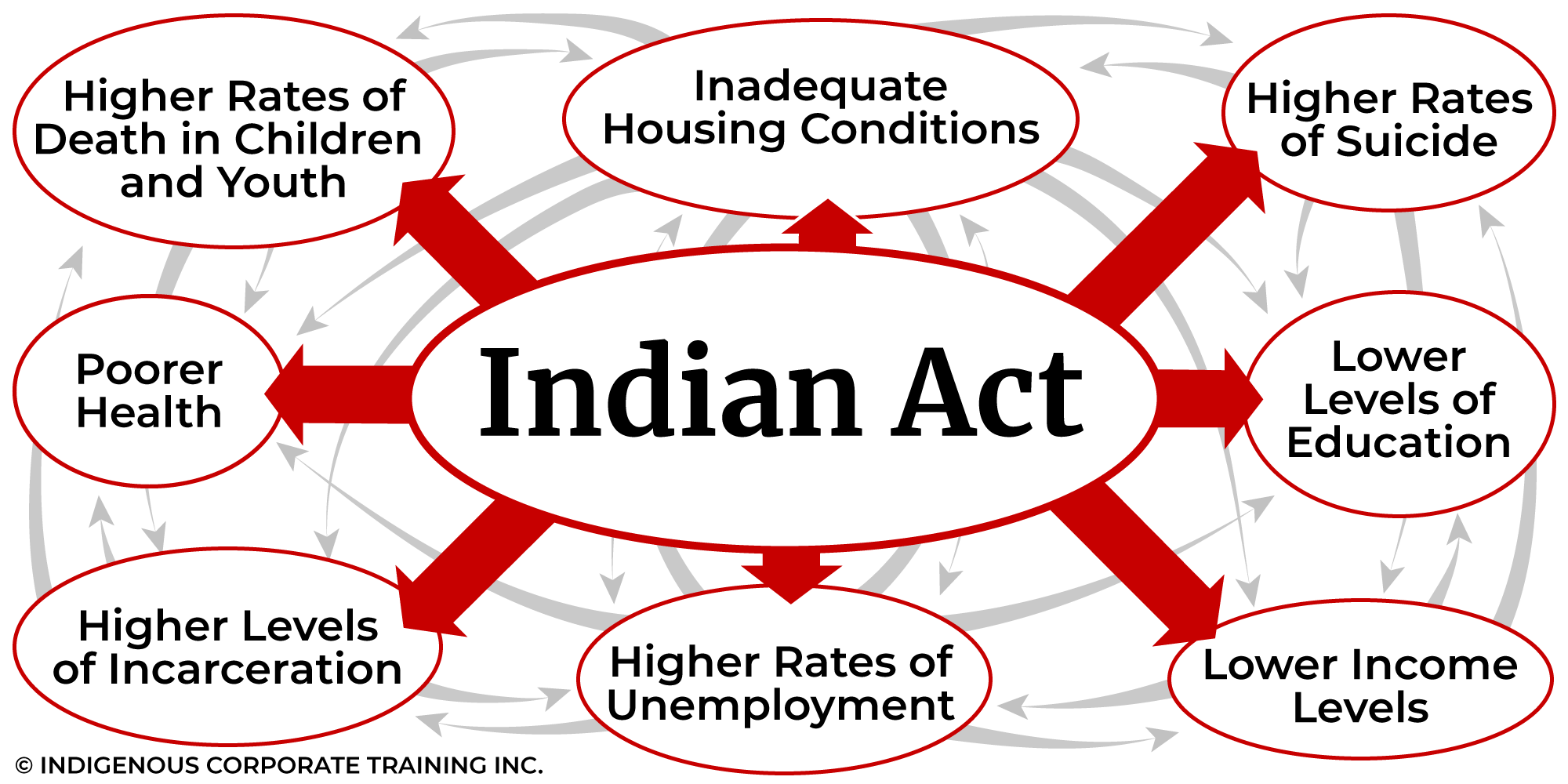

When the Indian Act, 1876 was imposed on Indigenous people, assimilation into European culture was the goal. Ironically, a few years later, in 1881, the Indian Act restricted Indigenous involvement in local economies with the permit systems, which controlled their freedom to leave their reserves and to sell their products, thereby stymying its original goal. Government policies and actions over time have perpetuated cycles of poverty, discrimination, bias and marginalization over many generations.

Under the Indian Act, registered “Indians” living on reserve cannot own the land under their houses; therefore, their houses cannot be sold - which makes it impossible to build up equity in your home, as is possible for non-Indigenous people.

The federal government’s Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy has concrete poverty reduction targets of a 20% reduction by 2020 and a 50% reduction by 2030 based on Canada’s Official Poverty Line, which, relative to 2015 levels, would lead to the lowest poverty rate in Canada’s history.

These targets also align with target 1.2 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 1: “By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions.”

For further learning, our Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® training has helped thousands of individuals and organizations better understand Indigenous history, culture and how the Indian Act affects Indigenous Peoples today.

[1] Average Income in Canada: Does Your Salary Measure Up?

[2] ibid

[3] Disaggregated trends in poverty from the 2021 Census of Population

[4] Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy

Featured photo: Unsplash

1 min read

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...

Education is considered a human right in Canada. Yet, while Canada has one of the world's highest levels of educational attainment, the graduation...

Indigenous awareness is a broad term – I know because my onsite and public workshops are dedicated to helping people understand the full extent of...