Indigenous Engagement vs Indigenous Consultation. Here's the Difference.

Why do we see some organizations call their work Indigenous Engagement and some refer to it as Indigenous Consultation? To find the answer we need to...

Recent events in Canada have shown that resource development projects can face extensive resistance from the affected Indigenous communities if consultation efforts are not meaningful, and comprehensive, and address the concerns of Indigenous Peoples and not just the legal requirements. With all of the court cases on the books defining title and the duty to consult, all the examples of how not to conduct engagement, and all the examples of how to effectively and successfully engage with a community, it is surprising that at this point in our history that we are still climbing the learning curve.

I launched my company, Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., in 2002, with one Indigenous Awareness course. However, I soon realized that there was a very great need for a course that combined awareness with some guidance on how to effectively consult and work with Indigenous communities. So, I pulled together my notes and created Working Effectively with Aboriginal Peoples™ and a book of the same name that was part of the course. The title of the course and the book (now in its 4th edition) has evolved to Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®.

In gathering field notes for the book and course, I noticed that some project proponents claimed their consultation process was going well yet at the same time, the Indigenous communities they were working with had a different perspective. In particular, the proponents who left consultation solely or largely in the hands of the government were experiencing additional costs, project delays, and sometimes resistance, all of which put their project into major slowdown mode. They were unaware or had little knowledge of any issues the communities had with their project because they themselves had not engaged directly with the community/ies. (Note the change in terminology here. Do you know why we did it?) Alternatively, those proponents who consulted with the communities early on in the process were not experiencing the same degree of resistance.

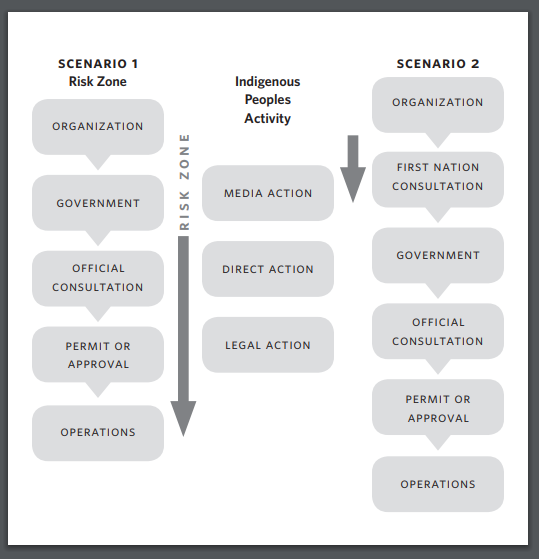

To put in perspective the potential risk associated with failing to include the Indigenous communities early on in the process, I created this Risk Assessment Model:

Take a look at the diagram and the differences between the two approaches to consultation. On the left, you see that First Nation consultation is not even part of the process. While, legally, it is the Crown, not industry that holds the duty to consult, it could be unwise to leave the consultation solely in the hands of government agencies. Sometimes governments make project approval decisions without adequate consultation (there have been over 150 Supreme Court of Canada cases since Delgamuukw and Gisday'way) which can put a project on the pathway to legal or regulatory process challenges and ensuing costly delays. Some project approvals are sent back for more consultation.

Whereas, on the right side of the diagram, you see an approach specifically designed to measure and mitigate risk early in the development process. This approach, which has the proponent leading the consultation, and doing so early on in the process, means key issues, priorities, and community decision-makers are identified. By engaging early, a project proponent gains an increased likelihood of earning community support thereby mitigating the risk of the project delays due to resistance from the community.

Meaningful consultation means listening to the concerns of the community/ies, discussing those concerns, and being prepared to accommodate those concerns. Underlying all engagement and consultation strategies should be the awareness that while you are there for the duration of your project, the people you are engaging with intend to be in the area forever, so decision-making regarding land use will be concerned with a long-term view that extends well beyond your project.

Meaningful consultation can only happen when the people doing the engagement and those who have the decision-making powers have:

a working understanding of s.35 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982

a working understanding of and respect for Indigenous protocols

a working understanding of and respect for the role of hereditary chiefs and other high-ranking members of the community/ies

a working understanding of and respect for Indigenous rights and that those rights are collectively held on behalf of the community which means any decision regarding land use is a potential infringement of the rights of the whole community

a working understanding and respect that the “divide and rule” approach to engagement and consultation is very risky and an unwise tactic

a working understanding of and respect for the governance structure of the community/ies

a working understanding of and respect for the concept of connectivity

a working understanding and respect for the fact that each community needs to be uniquely engaged (one size does not fit all)

Failure to devote adequate time, effort and resources to meaningful consultation with affected Indigenous communities can have devastating impacts on a project. Indigenous communities do not need expansive financial resources to launch significant and effective resistance to a project. Here are three ways in which a project can be disrupted, delayed or completely derailed.

Negative media campaigns are never good for an organization so actions should be taken to avoid triggering an Indigenous community to launch a negative media campaign because of a faulty engagement process.

In the not-so-distant past, negative media meant the Indigenous community would write letters to the organization, the government and the local media. Now, however, with the global reach of social media, it does not take long for a negative media campaign to gain momentum.

Direct action can run the gamut from relatively benign information pickets to blocking access to the contested area to nationally disruptive rail blockades. These types of direct actions are often magnified with accompanying negative media campaigns.

There have been some extremely lengthy blockades (the longest continuous blockade is the Grassy Narrows blockade that began in 2002) and some blockades that have had tragic outcomes involving loss of life (Oka, Quebec; Gustafson Lake, BC).

Indigenous Peoples can also resort to tying up a project in the courts via a Judicial Review. If they request a Judicial Review of the meaningfulness and adequacy of the government consultation process, a project can be delayed for two to five years. A delay of the duration incurs project delay costs, legal fees and the possibility of market conditions and changes in government.

As shown in the first few months of 2020, failure on the part of the proponent to identify and respect key issues, priorities and decision-makers and the key project-related concerns can lead to significant, expansive and ongoing resistance to a project. The Coastal Gas Link project ran into resistance from all three types of negative actions listed above. The direct media action included protests along national rail lines and drew international attention.

Featured photo: Coast Salish house post and Haida totem pole, White Rock, BC. Photo: Joe Mabel, Flickr.

Why do we see some organizations call their work Indigenous Engagement and some refer to it as Indigenous Consultation? To find the answer we need to...

The foundation of meaningful engagement with an Indigenous community is trust. Earning that trust will take time, consistency, and transparency. The...

Did anyone notice that the Province didn’t officially respond to Tsilhqot’in until September 11, 2014? Why? Things have changed in a way that is hard...