What Reconciliation Is and What It Is Not

For a very long time, mainstream Canadians were unaware of the horrors and conditions that 150,000 Indigenous children endured in the Indian...

The Anglican Church has been working towards reconciliation for a long time and in BC, that work is being guided by Bishop Logan McMenamie, who is in turn, guided by Kwakwaka’wakw Elder Alex Nelson. Bishop McMenamie took the time to speak with us about the steps the church is taking toward reconciliation.

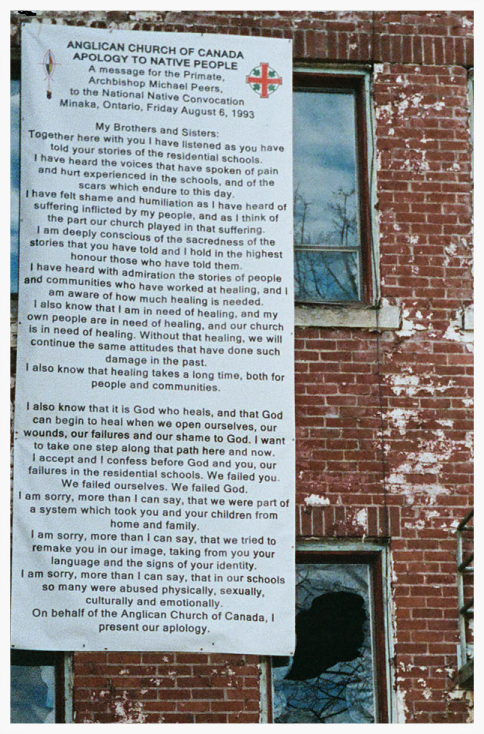

Why was it important to you to participate in the decommissioning of St Michael's Residential School and to have the apology of the Anglican Church hung on the wall of the school during the ceremony?

Why was it important to you to participate in the decommissioning of St Michael's Residential School and to have the apology of the Anglican Church hung on the wall of the school during the ceremony?

It is very important for us as Anglicans to understand the great responsibility we carry in relation to the Residential Schools. It was important to me to stand there with them and it was important to the Diocese to be there through me, to have the opportunity to say “We recognize what the school did, the horror of the school, we want to be here at the time when you symbolically demolish the school.”

It was important to give an apology, to say “We did this”. But the apology is not the ending it is the first step in a new relationship. It’s not about what we can do for First Nations people, or what we can say to First Nations people, it’s what we are going to hear, and how we are going to learn. It’s part of the symbolism of being there, and saying “This is who we are, and this is who we hope to become through reconciliation.”

It’s a very sad part of our history. As a national church, and in this diocese, there is a real commitment for us to move ahead, and to walk with First Nations as they regain who they are.

Has your diocese accepted the need to acknowledge that past and work towards reconciliation?

Wherever I am in the diocese I begin by saying “We are on traditional First Nations land and we give thanks for their hospitality” and I get the usual letters disagreeing with that statement. But, overwhelmingly the majority of the parishioners have moved from “What can we do to help the survivors?” to “How can we walk with First Nations people and learn from them?” Acknowledging the traditional lands has become part of our culture.

A residential school survivor spoke of his experiences to about two hundred parishioners at a synod in Nanaimo. As he was speaking, people began standing up and by the end of his talk the majority of people were standing in solidarity with him; it was very powerful.

When our new Dean was inducted, rather than have the Royal Anthem accompany her, Alex Nelson’s family drummed her in. And when I became Dean of the cathedral, I chose to be drummed and sung in rather than have the Royal Anthem. When First Peoples share their culture in our big house, they make us a better people and a better church because they open their hearts to us and we open our hearts to them.

How do you help your parishioners work toward reconciliation?

I draw upon the wisdom and guidance of Alex Nelson, a Kwakwaka’wakw Elder, and others as we move ahead as a Church.

In addition to reminding parishioners on whose land we gather, I try to incorporate the traditional language of the community we are in. I once said to Alex “How about if we use your language?” And he replied, “We’ve been using yours for over 150 years so it’s time you learned ours!”

Every parish in the diocese, either verbally or in their bulletin, recognizes the traditional land they are on.

Every parish in the diocese has a mandate from me to reach out to the First Peoples, learn from them and build relationships with them.

Some First Nations people have a profound strength that allows them to forgive and strive toward reconciliation. Where do you think they get that strength?

The strength of First Nations people to forgive amazes me. The National Anglican Church has been working on reconciliation for a long time. We created a series of videos and one of the first was of the horrors of the residential schools and what that meant culturally, spiritually, loss of language and tradition. One survivor interviewed said, “Jesus better come back again because the Church got it wrong so he needs to come back and tell them to do it right.” At the end of the video another man talked about the residential school and what had happened to him. He finished by saying “But I still love the church” – it gave me tingles up and down my spine. I asked myself if I had gone through what he had gone through, would I still love the Church? His statement about still loving the church made me recognize the profound strength and spirituality of First Nations people. And I think that profound strength comes from First Nations culture; they are grounded in their creation, their Creator, and being part of the land, sea and sky. The culture, the tradition, the connection with the land that goes back generation after generation and the history that has formed them as a people - I believe that is where the ability to forgive and to work towards reconciliation comes from.

Originally posted December 2015.

Featured photo: St. Michael’s Indian Residential School at Alert Bay, British Columbia, Canada. Photo: David Stanley, Flickr

For a very long time, mainstream Canadians were unaware of the horrors and conditions that 150,000 Indigenous children endured in the Indian...

Trade and specialization were common to First Nations in Canada and throughout the Americas in the pre- and early contact periods. Moreover, public...

1 min read

The report of my death was an exaggeration. Mark Twain Is reconciliation dead? Our trainers and staff frequently are asked this question, and...