What’s the Difference Between Historic and Modern Treaties?

We have received requests to provide a description of the difference between historic and modern treaties. This article attempts to answer the...

Canada is renowned for the wealth and diversity of its natural resources and has long relied on royalties from extractive industries to contribute to the gross domestic product.

Governments derived $22 billion annually on average from the natural resource sectors during 2012-2016. There are 418 major resource projects under construction or planned over the next 10 years in Canada, worth $585 billion in investment. [1]

Resource extractive projects typically are either fully located on the traditional territories of Indigenous communities, pass through their territories, or some aspect of the development, such as transportation routes, has a bearing on Indigenous lands. In many scenarios, the natural environment and section 35 rights that have sustained the Indigenous Peoples for millennia are impacted which in turn requires consultation.

Extractive and renewable resource projects hold the potential to contribute to economic and social development opportunities for Indigenous communities. For example, since 1974, Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBA) have been a common vehicle by which Indigenous communities can derive benefits from these projects.

Natural Resources Canada estimates that since 1974, a total of 335 IBAs have been signed for 198 mining projects. Of these IBAs, 265 remain active and cover various stages of project development, from exploration to reclamation. Recent research from the Northern Development Ministers Forum indicates there has been a significant increase in the number of IBAs signed in the past two decades. Notably, the number of IBAs signed between 2001 and 2005 and between 2006 and 2010 grew from 23 to 102, representing a fourfold increase. [2]

Indigenous communities can also derive benefits from resource development projects through resource revenue sharing (RRS). RRS is increasingly making its way into talks between provincial and Indigenous governments. But this is not a new concept or conversation. The roots of this concept and conversation go back to at least the mid-1840s when Anishinaabe leaders began requesting a share of the resources extracted from their land.

I was recently reading the 600-paragraph ruling by Justice Patricia Hennessy on Restoule v. Canada (Attorney General), 2018 ONSC 7701, which regards treaty payments, and became intrigued by the paragraphs relating to comments Anishinaabe chiefs made about compensation for materials removed from their lands…..in the mid-1840s. At that time “copper fever”, active on the American side of Lake Superior, had crept up north to the Upper Great Lakes Region. And with the “fever” came an influx of prospectors, bearing government-issued mining licences, into Anishinaabe territory. Anishinaabe leaders were as concerned by the presence and activities of the prospectors as they were about the issuance of permits for timber harvesting and sales, and the activities of surveyors who were laying out town lots. The government did not have a treaty with them, therefore, these activities were direct challenges to their jurisdiction over the land. They wanted compensation for the resources extracted and recognition for their claim to the land.

Here are some excerpts I found very compelling:

Page 29:

[116] By July of 1848, Chief Shingwaukonse complained personally to the Governor-General in Montreal that “the lands which in former times they occupied and considered their own have lately been taken possession of by various mining companies” and that they were otherwise restricted in their ability to make a living, either by hunting or woodcutting.

[117] Game was becoming scarce in the territory. Chief Shingwaukonse signalled that he could foresee the impact of mining and development on the next generation “when the animals of the woods should have grown too scarce for our subsistence.”

[118] The influx of Crown-sanctioned mining exploration and development increased the tensions over jurisdiction and control of the territory and became one of the key triggers for the negotiation of the Robinson Treaties.

Page 32:

August 1846: At the Council convened at Sault Ste. Marie, Anderson asks the Anishinaabe to justify their claims to the land. In their speeches, Chief Shingwaukonse and Chief Peau de Chat complain about the mining activities occurring in the territory and the negative effects those activities are having on the Anishinaabe way of life. Both Chief Shingwaukonse and Chief Peau de Chat further described to Anderson that the destruction of the landscape had driven the game from the hunting grounds and the people had been left to starve:

The Great Spirit, we think, placed these rich mines on our lands for the benefit of his red children, so that their rising generation might get support from them when the animals of the woods should have grown too scarce for our subsistence. We will carry out, therefore, the good object of our Father, the Great Spirit. – We will sell you these lands, if you give us what is right – at the same time, we want pay for every pound of mineral that has been taken off of our lands, as well as for that which may hereafter be carried away.(emphasis added)

August 10, 1846: Chief Shingwaukonse and other Anishinaabe Chiefs make a further petition to Governor General Lord Cathcart, reasserting their claim to the lands. The petition states:

Already has the white man licked clean up from our lands the whole means of our subsistence, and now they commence to make us worse off they take everything away from us father.

Page 33:

The Chiefs proposed a means by which the newcomers could access, explore, and develop mining projects on the land with the consent of the Anishinaabe. They suggest that the best way to solve the problem was to make a treaty, similar to the one Chief Shingwaukonse had proposed a year earlier, but which was now essential considering the arrival of exploring parties with Crown-authorized licenses:

And [the Chiefs] are very desirous of avoiding the unpleasant collisions into which they are in danger of being brought with the explorers.

July 5, 1847:

They underscore the legitimacy of the Anishinaabe claims and complain about a recent visit by prospectors:

[A]bout that time now one, then another whiteman came stealing along our shores and entering into our wigwams told us in answer to our enquiries that they were come to look for metals which they heard were to be found in our land and asked us to shew them the copper, but this we refused… when we heard several persons say that some of our land had already been sold to those explorers…

Here we are in the 21st Century and resource revenue sharing based on recognition of title is, in some jurisdictions, a reality. In retrospect, I think there is much that could have been accomplished with the unrealized revenue from past resource development projects if only the wisdom in the words of those long-ago chiefs had been recognized and respected.

[1] Norah Kielland, Supporting Aboriginal Participation in Resource Development: The Role of Impact and Benefit Agreements, Research Publications, LIbrary of Parliament, 2015

[2] 10 Key Facts on Canada’s Natural Resource

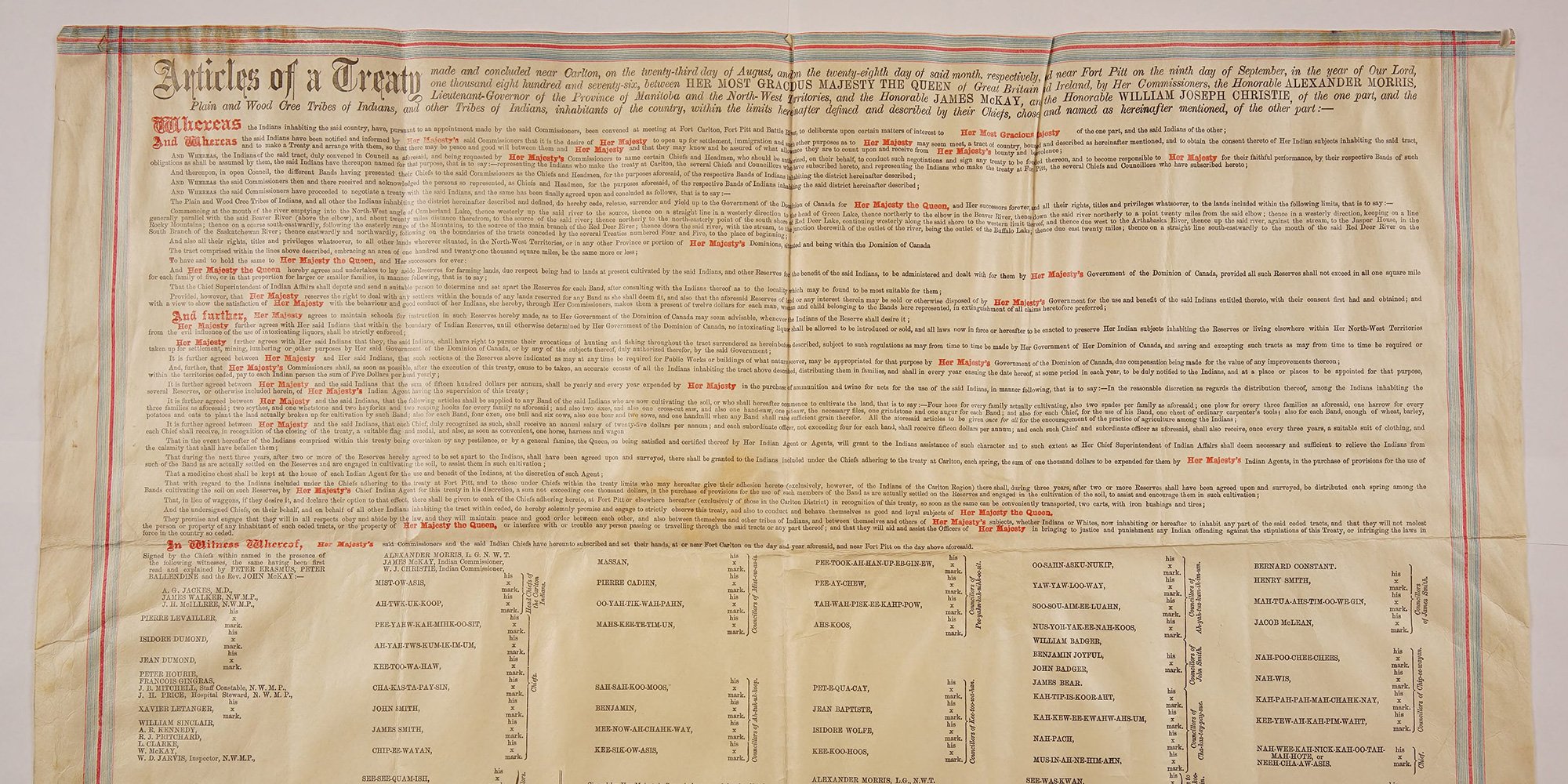

Featured photo: Shutterstock

We have received requests to provide a description of the difference between historic and modern treaties. This article attempts to answer the...

There are more and more articles in the news about the value of Indigenous traditional knowledge being taken into account in climate change studies,...

Treaties are negotiated agreements that define the rights, responsibilities and relationships between Indigenous groups and federal and provincial...