Reading for Reconciliation: 6 Books on Residential Schools

To honour and support the Closing Events of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), May 31 - June 3, 2015, in Ottawa, we have...

6 min read

Bob Joseph September 17, 2013

Shelagh Rogers, OC, journalist, host/producer of the CBC radio program The Next Chapter and Chancellor of the University of Victoria, is an Honorary Witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She took some time from her very busy schedule to speak with us about her passion for reconciliation and her hopes for Canada in terms of reconciling the past to create a better future.

Shelagh Rogers, OC, journalist, host/producer of the CBC radio program The Next Chapter and Chancellor of the University of Victoria, is an Honorary Witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She took some time from her very busy schedule to speak with us about her passion for reconciliation and her hopes for Canada in terms of reconciling the past to create a better future.

What was your path to becoming an Honorary Witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and what is your mission as an Honorary Witness?

I was hosting a program called “Our Home and Native Land” that looked at Aboriginal issues, triumphs and tragedies in Canada. In every conversation, residential schools came up and I began to realize that I did not understand what residential schools were. I had a vague idea that they were boarding schools – that because some reserves did not have schools, the children had to leave for schooling. I did not at all know the real purpose of residential schools so I decided to educate myself. My producer put me in touch with Dr. Maggie Hodgson and she arranged for me to meet and interview the Jones family of Nanaimo; John Jones had attended Alberni residential school. I sat and talked with John, his daughter Lillian, and her daughter Victoria, and that moment was the beginning of my real education on residential schools. The interview resonated – we had the largest response to any piece I had ever done. People wrote in and said this can’t be happening, this can’t be Canada; others wrote in to say this is ancient history, why can’t “they” “get over it” but by far, 95%, were honestly shocked. The program aired about four weeks before the apology [I will link to the apology]. I guess that put me on the radar of the TRC. I was the second Honorary Witness named and was installed as an Honorary Witness in 2011, in Inuvik, at the TRC’s Northern Gathering.

My mission is to listen, learn and then transmit, and create understanding. As a Witness, you keep the memory and you take the story further down the road and deliver it to more people. I have been very busy talking in churches, doing dialogues, meeting in community hall basements, and book clubs – just trying to get the real story of our country out to as many people as possible. It has really taken over my heart. It is bigger than just telling the story – I want to see policy change, curriculum change, to see concrete fixes in civil society that will enable us to have much better partnerships than we have right now.

The media, I am very sorry to say, have not taken the opportunity to give gavel-to-gavel coverage of what the TRC has been doing. I do wish there had been a real commitment to cover what has been going on.

If we can get past the “you are not this” and “you are that” aspect then we will find that we have so much more that can bring us together. One thing that does bring us together is our shared history – as Justice Sinclair always says, “this didn’t happen only to Aboriginal people, it happened to all Canadians” – and we are lesser for it.

We will be who Canada is supposed to be once we get this partnership up on its legs and thriving in a healthy way. The greatest enemy of reconciliation is indifference and complacency.

What drives your passion for reconciling the intergenerational trauma of the residential school system of Aboriginal people in Canada?

It comes down to the Jones family. It was seeing this family come together, to talk about John’s experiences, for the first time. Their collective story, and John’s individual story of Alberni, moved me to tears and moved me to action. It was this family that made me fully realize that it did not happen to just one person and just one generation. Multiply this exponentially and you have an idea of what it is like for some Aboriginal families.

I carry the Jones family in my heart and we have become great friends. They have taught me about resiliency, love, caring, forgiveness and honour. If every non-Aboriginal Canadian could have this sort of relationship they would be overjoyed with the beauty of it.

The sense of what is right and what is just is also part of what drives my passion.

How do you process the emotional trauma that you encounter when talking to survivors – how do you not let it overwhelm you?

I will always remember the first TRC gathering I attended in Inuvik – I had vowed that I would not get upset because I was witnessing someone else’s story – it wasn’t mine to get upset over. But, I did get upset and all of a sudden I felt an arm around me and it was a social support worker, an Inuit man, who had very likely gone to residential school, and he was giving me – the Honorary Witness and a non-Aboriginal person, support because I was upset. When I thanked him he said “this is what we do” and he meant not only as social support workers but also as human beings.

The day that had been chosen for me to bear Witness was Canada Day. As I listened I began to feel horrified and appalled at my Canada. How could this go on in my beautiful country? I didn’t think I was going to be able to bear witness so I was sent to see an Elder. He had not been told anything about me. I sat down and started to talk but he told me to stop talking. He sat and looked at me, for I don’t know how long. He finally said to me “The real shame would be to feel no shame. You are beginning a real journey, the longest journey, and that is from the head to the heart.”

I always feel not quite right about feeling overwhelmed because I didn’t go to a residential school but it is hard, but important, to hear the statements of Survivors. I take part in the smudging and cedar brushing ceremonies that are part of the TRC events and they ground me. And that is a real honour. Still, when I come home from a TRC event, I need a few days of quiet; I can’t jump right back in the saddle with author interviews.

When you first met survivors and listened to their memories and the impact residential schools have had on them and their children, what surprised you?

The level of horror and cruelty and how the government, Indian agents and church turned a blind eye. I frequently hear people say “but they meant well” and when I hear that I always recall Justice Harry LaForme saying “what was it they meant well to do?” This was all about assimilation, about losing a culture. What surprised me was reading that it was law. Children were stolen. They were literally grabbed from their families. It was shocking but that was the tip of the iceberg and as with all icebergs, 9/10’s is unseen. We won’t know the extent of it until all the documents are turned over – there is so much we don’t know.

I am surprised by the fact that more people weren’t fighting for change. Canadians pride themselves on being a caring society but I don’t think we were during the residential school era. What surprises me is how many people still don’t get it.

It also surprises me that it is not in our history books.

Another thing that surprises me is the resiliency of the survivors and their power for forgiveness. I am learning from survivors that when you forgive someone, or when you receive forgiveness, a weight comes off. I am also surprised at the courage and strength the survivors must have to stand up and talk about what happened to them. I asked John what he would consider a meaningful apology and he replied that he would like the Prime Minister to come to his land and offer a sincere apology and then he would in turn, honour the Prime Minister with a feast. It blew my mind but this is what is embedded in his culture as a Coast Salish man. This power of forgiveness and honour has survived every effort made to take it away. We have so much to learn.

How can acknowledging and understanding this aspect of Canada’s history improve our future?

Understanding the history means we can actually look people in the eye in the present. We would be acting with honour if we acknowledged and understood the impact that residential schools had on all Canadians. I feel so sorry that the apology seems to have been an ending when it should have been a beginning. Acknowledging and understanding could actually decolonize Canada – it could bring everybody together in an equitable partnership.

As a recipient of the Order of Canada, what is your wish in terms of how the curriculum in Canadian schools should be changed so that children learn about residential schools?

The motto of the Order is “They desire a better country”. I really believe citizenship is a beautiful gift and it comes with a duty to make sure that your country is as strong and compassionate as it can be. The history simply has to be taught in schools; children have to know the real history. The north has really taken the lead as it is being taught in northern schools and that is great.

You co-edited Speaking My Truth: Reflections on Reconciliation & Residential School, for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation – where is the book available?

It is available on line at speakingmytruth.ca and it’s free and they will send it to you for free. I am not sure how much longer it will be available though. It is included in the kit of all 1500 first year students at Nipissing University which is wonderful.

We are honoured to have the opportunity to interview some really fascinating people who share their insight and experience on working with Aboriginal Peoples.

Here's a reading list for reconciliation for adults

And here's another list of books on residential schools for children

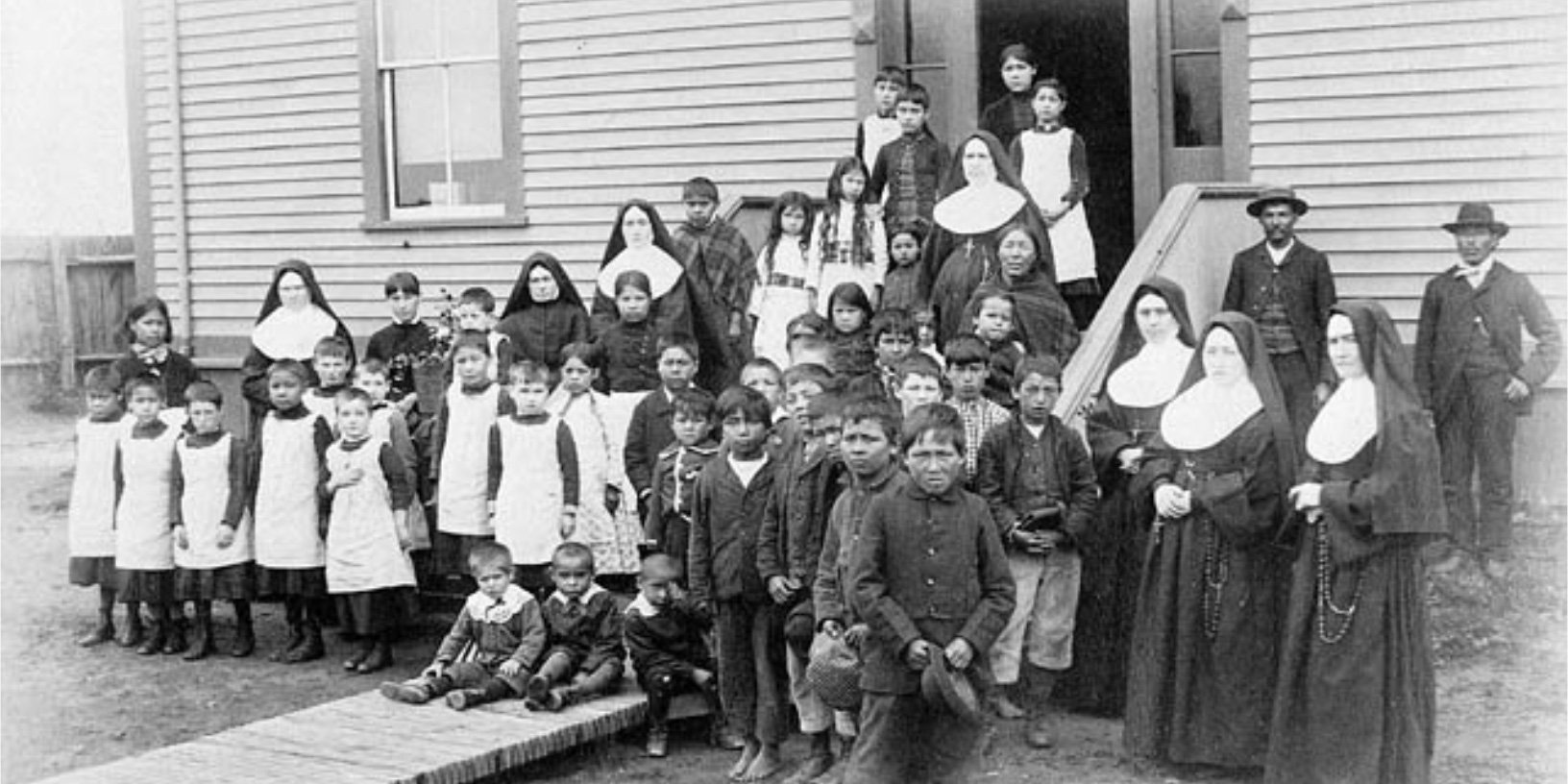

Featured photo: Pexels

To honour and support the Closing Events of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), May 31 - June 3, 2015, in Ottawa, we have...

This article includes a video of a conversation I had with my father Chief Robert Joseph, O.C., O.B.C., about his first day at residential school and...

On April 1, 2022, I held my breath as I am sure thousands of other Indigenous Peoples did while listening to Pope Francis publicly address the...