What Is the Root Cause of Indigenous Education Issues

Fifty-eight percent of young adults living on reserve in Canada have not completed high school, according to the 2011 National Household Survey...

3 min read

Bob Joseph February 18, 2014

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children literally scooped from the arms of their parents and placed in boarding schools or the homes of middle-class Euro-Canadian families. This period of child apprehension arose in the wake of the closing of the Indian residential schools.

The Indian residential school system was designed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture by removing them from their families and homes and placing them in government and Christian-run schools. These schools were considered an important instrument of the assimilation policy because they “…took [the Indigenous child] from the reserve and kept him in the constant circle of civilization, assured attendance, removed him from the “retarding influence of his parents …” Indian Act - all of which was done to “help” Indigenous Peoples, and bring them forward into “civilized” society.

The phasing out of residential schools began in the 1950s due to a growing public awareness of the devastating impacts on the children, families and communities - the last one closed in 1996. The assimilation program did not die out at that time, however, it simply deployed a different tactic.

NOTE: In 2019, former students of Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet in what is now known as Nunavut won a court battle to have Kivalliq Hall included as an IRSSA-Recognized School. While this 2014 article states that the last residential school in Canada to close was in 1996, Kivalliq Hall's closing in 1997 is an important detail to note when recounting and learning about Indigenous history.

The government decided that Indigenous children would receive a better education if they were placed in the public school system. In 1951, the Indian Act was amended to allow provincial governments to provide services to Indigenous people in areas where the federal government formerly had not, and these new services included child protection. In 1952, in BC, less than 30 Indigenous children were in provincial care; by 1964, nearly 1500 or 34 percent of all children in provincial care, were Indigenous. Residential schools continued under the guise of boarding schools for the children of families who were deemed incapable of caring for their children. Not all the children were placed in boarding schools - many were adopted by non-Indigenous families and raised within that culture.

“Sixties scoop” was coined by Patrick Johnston who wrote the “Native Children and the Child Welfare System” report in 1983. In his report, Johnston quotes a social worker who said “with tears in her eyes - that it was a common practice in B.C. in the mid-sixties to ‘scoop’ from their mothers on reserves almost all newly born children. She was crying because she realized - 20 years later - what a mistake that had been.”

Social workers were not expected or required to have experience, skills or knowledge relevant to the traditions, culture or history of the Indigenous communities within their jurisdiction. Their evaluation of a nurturing and safe family life was based upon their own, often middle-class, Euro-Canadian perspective - traditional Indigenous family life and diet were generally neither understood, valued nor recognized. That perspective, when viewing the poverty, unemployment and substance abuse that affected many Indigenous communities led to the assumption that the children were not receiving adequate care and so were removed - frequently without warning or consent of the parents. This scooping of children without consent continued in BC until 1980 at which time the Child, Family and Community Services Act stipulated that social workers were required to notify band council if a child was to be removed.

The apprehension of children from their families and communities and placement in boarding schools or adopting out to non-Indigenous families is considered “cultural genocide” under the UN Convention of Genocide (1948). Article 2(e) states:

'forcibly transferring children of the group to another group' constituted cultural genocide when the intent is to destroy a culture. Protection of children of Indigenous Peoples was further enhanced by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 7 that states 'Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group to another group.'

If you do the math you will realize just how many generations of Indigenous people in Canada have been affected by the assimilation programs of the Indian Act.

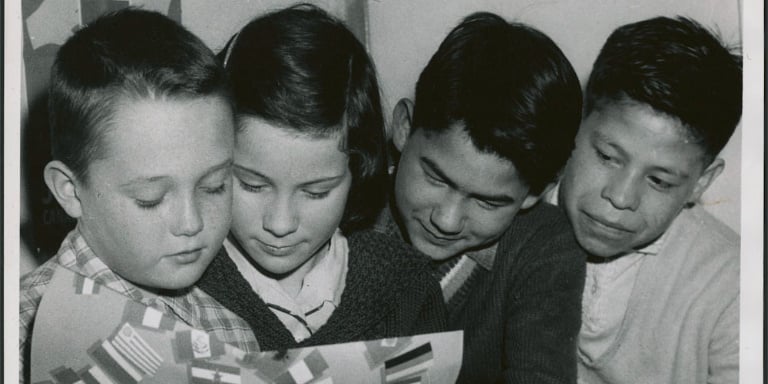

Featured photo: Department of Citizenship and Immigration / Library and Archives Canada / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / e011373519 ; Copyright: Government of Canada.

Fifty-eight percent of young adults living on reserve in Canada have not completed high school, according to the 2011 National Household Survey...

Indigenous awareness is a broad term – I know because my onsite and public workshops are dedicated to helping people understand the full extent of...

The definition of “myth”, according to the Oxford Canadian Dictionary, is “a widely held but false notion.” When it comes to the topic of Indigenous...