The Indian Act & the Politics of Exclusion

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

When an Indian woman marries outside the band, whether a non-treaty Indian or a white man, it is in the interest of the Department, and in her interest as well, to sever her connection wholly with the reserve and the Indian mode of life, and the purpose of this section was to enable us to commute her financial interests. The words "with the consent of the band" have in many cases been effectual in preventing this severance….The amendment makes in the same direction as the proposed Enfranchisement Clauses, that is it takes away the power from unprogressive bands of preventing their members from advancing to full citizenship. [1]

Prior to European contact, and the ensuing fundamental disruption to the traditional lifestyle of Indian communities, women were central to the family, were revered in communities that identified as matriarchal societies, had roles within community government and spiritual ceremonies, and were generally respected for the sacred gifts bestowed upon them by the Creator. The Indian Act disrespected, ignored and undermined the role of women in many ways. This dissolution of women’s stature coupled with the abuses of the residential school system has been linked as a significant contributor to the vulnerability of Indigenous women.

In 1742, Joseph-Francois Lafitau, a French Jesuit missionary and ethnologist wrote about his observations of the role of women in the Iroquois-speaking nations:

Nothing is more real, however, than the women’s superiority. It is they who really maintain the tribe... In them resides all the real authority: the lands, the fields, and all their harvest belong to them; they are the soul of the councils, the arbiter of peace and war... they arrange the marriages,; the children are under their authority; and the order of succession is founded in their blood. [2]

“Under the statutes and policies of the Indian Act, women were not only discriminated against as Indians but also as Indian women.” [3] Indian Act policies subjected generations of Indian women and their children to a legacy of discrimination when it was first enacted in 1876 and continues to do so today despite amendments. Federal law in the late 1800s that defined a status Indian solely on the basis of paternal lineage - an Indian was a male Indian, the wife of a male Indian, or the child of a male Indian - continues to be a quagmire of discrimination and disrespect towards women.

As a result of the 1869 Lands and Enfranchisement Acts, and ensuing Indian Acts and amendments, the following bullets outline the ways and means Indian women have been disregarded, dishonoured and dismissed:

For more information on the outcome of federal attempts to rectify this discrimination, please read Indian Act and Women’s Discrimination Bill C-31 and Bill C-3

[1] Deputy Superintendent General Duncan Campbell Scott, Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Volume 4, 1996

[2] Cora Woolsey, The Indian Act: The Social Engineering of Canada’s First Nations

[3] Martin J. Cannon, First Nations Citizenship, An Act to Amend the Indian Act (1985) and the Accommodation of Sex Discriminatory Policy

[4] Dr. Peggy J. Blair, Rights Of Aboriginal Women On- and Off-Reserve, 2005

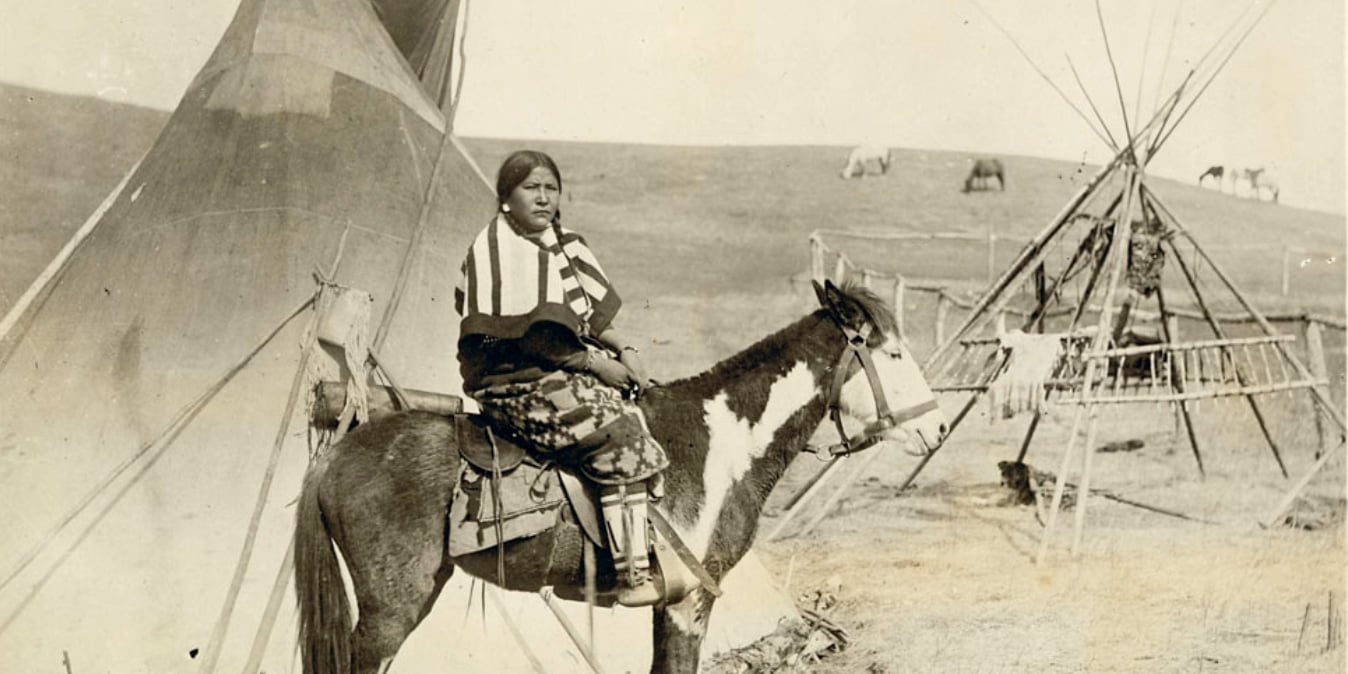

Featured photo: Plains Indigenous woman on horseback, Walter Lake, Alberta, 1920-1930. Photo: Archives / Collections and Fonds - 4589638

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

Indian Act policies subjected generations of Aboriginal women and their children to a legacy of discrimination when it was first enacted in 1876 and...

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other...