1 min read

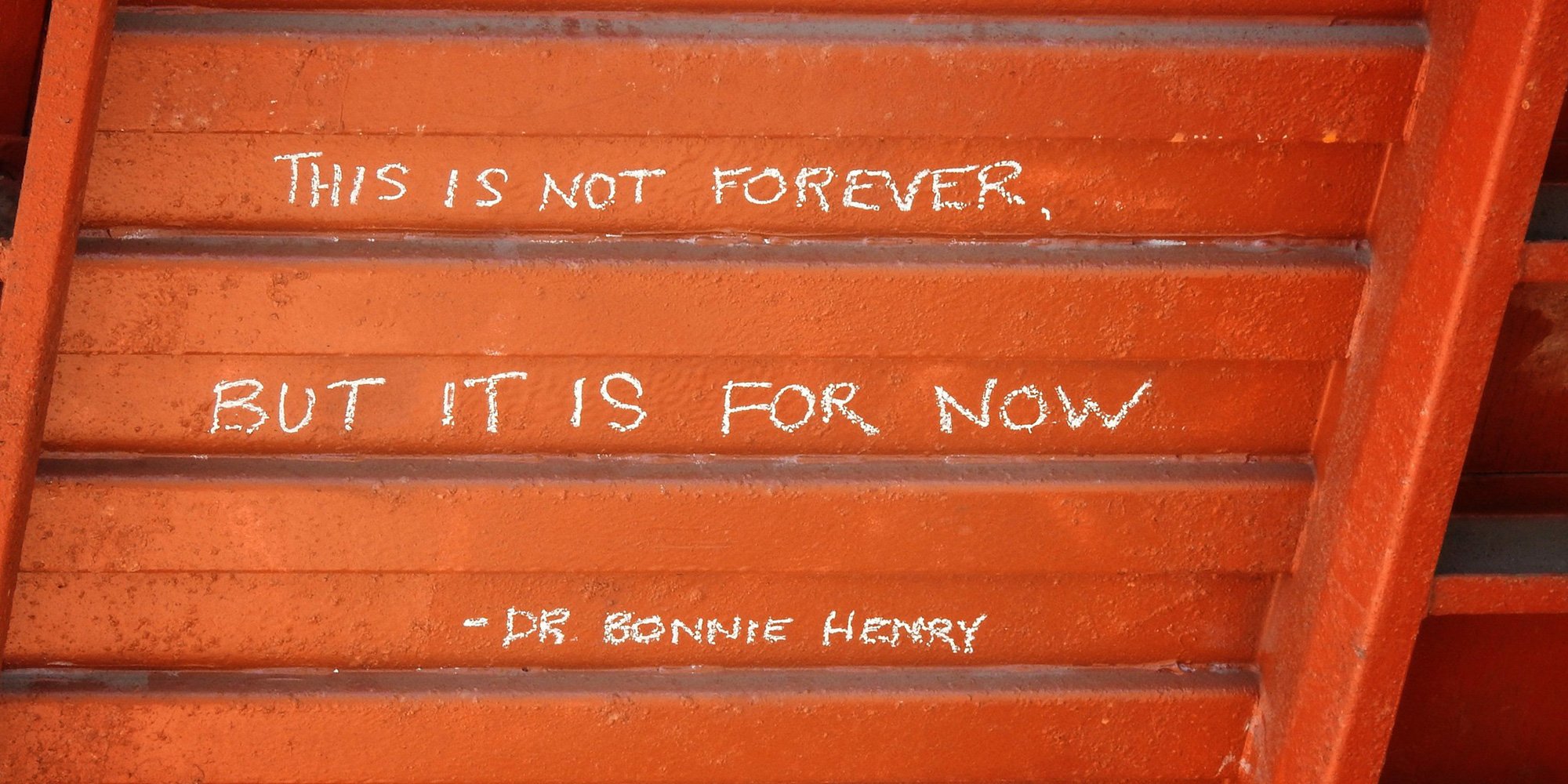

Dr. Bonnie Henry, Elders, Reconciliation, and COVID-19

When Dr. Bonnie Henry announced the death of an Elder from Alert Bay, I was struck by her compassion, her understanding of the enormity of the...

The COVID-19 pandemic could be the single greatest threat in this generation to the continuity of Indigenous cultures and the preservation of languages. The danger of infection has put on hold countless cultural activities and collective ceremonies around the world. Indigenous peoples in both urban and rural locals account today for over 476 million individuals spread across 90 countries, accounting for 6.2% of the global population, according to the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Indigenous communities are nearly three times as likely to be living in extreme poverty, and thus more prone to infectious diseases. Many indigenous communities are already suffering from malnutrition and immune-suppressive conditions, which can increase susceptibility to infectious diseases. [1]

Elders and seniors, many of whom have underlying health conditions, are the most vulnerable to the virus. And therein lies the threat to the preservation of culture. In oral societies with oral histories, they are the culture keepers - they know the language, the ceremonies, the protocols, the songs, the creation stories, and the cultural practices and are the holders of traditional knowledge. All of which have been passed down for generations. The cultural implications of the loss of an Elder are vast and impact future generations.

Whenever an elder dies, a library burns down.

Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Malian writer, historian and ethnologist

Many of us take our language for granted. Still, for a great many Indigenous cultures, their home language is synonymous with their culture, and it is their culture that defines them, governs them, and is part of their collective identity. And in Canada alone, a great many Indigenous languages were on the brink of extinction long before the pandemic arrived.

According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger project, “three-quarters of Indigenous languages in Canada are “definitely,” “severely” or “critically” endangered. The rest are classified as “vulnerable/unsafe." [1]

The loss of each language speaker decreases the likelihood of that language surviving. Nations that lose their language and all it contains are significantly more challenged in their pursuits of cultural revitalization.

The limitation on the size of gatherings is having a real impact on Indigenous communities as that restricts them from carrying out their cultural activities and ceremonies. Depending on how long it takes to develop and deliver a vaccine, the limitation on gatherings is going to have a long-term impact on the continuity of culture.

I am of a potlatch culture and was anticipating holding my first potlatch in the spring of 2020. Preparing for a potlatch takes time and requires many gatherings with my father, Chief Dr. Robert Joseph, and other hereditary leaders, Elders, and matriarchs. I receive detailed instructions from them on all the protocols and ceremonies for an event that spans a day to a couple of days or more. The information they share is oral in nature and shared through the generations since our Creation which dates back to the beginning of time.

I fear for the continuity of our cultures, which have withstood so many assaults over time. In my case, if I don’t have the opportunity to learn the protocols and ceremonies from our Elders, I won’t be able to pass those protocols along to my sons or instruct other children in the community when it is their turn to take part in our rituals, nor will they, in turn, be equipped to guide their children. The magnitude of the potential loss is frightening. Our Elders are our history and our future.

In previous generations, the threat to culture and language was manifested first through introduced viruses that wiped out entire villages and later through the assimilation policies of the federal government. Residential schools, which saw 150,000 children (of which 6,000 died or disappeared) between 1886 and 1997, taken from their homes and forbidden to speak their language or practice their beliefs dealt a significant blow to the continuity of culture. The ban on potlatches and other cultural ceremonies existed between 1884 and 1951. The impact on cultural continuity was severe, and nations and individuals across the country are still grappling with the historic and ongoing effects.

I am incredibly concerned about the health and safety of the Elders in my community and others. If you are wondering what you can do to help protect them, please respect those communities that have closed their territories to outsiders. They are protecting precious lives and the very future of their cultures.

[1] Nick Walker, Mapping Indigenous languages, Canadian Geographic, Dec 2017

Featured photo: Pixabay

1 min read

When Dr. Bonnie Henry announced the death of an Elder from Alert Bay, I was struck by her compassion, her understanding of the enormity of the...

June is National Indigenous History Month - a time for all Canadians - Indigenous, non-Indigenous and newcomers - to reflect upon and learn the...

The United Nations has declared 2022-2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. Many Indigenous languages across the world are in...