1969 White Paper - Rejected by Liberal Party of Canada

At the Liberal Party of Canada biennial convention in Montreal in February 2014, party members voted on a number of policy resolutions. Of particular...

There have been watershed moments in the history of Canada in which Indigenous leaders, outside of the courts, have stood up for their rights to the federal government and actually forced a change in policy direction. We’ve written about a couple of them in our Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® blog.

When the Indian Association of Alberta (IAA) presented Citizens Plus (the Red Paper), in 1970 as a counter punch to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, 1969 (the White Paper), it marked a significant watershed moment in the history of Indigenous leaders fighting on behalf of their nations for their land and recognition of their rights. Please note that we will use the term “Indian” in the rest of the article as that was the term used at the time. Today, based on community preference, we may use First Nations or other terms instead. Please download our Indigenous Peoples: A Guide to Terminology for a deeper dive.

Prior to the issuance of the White and Red Papers, was a period in which mainstream Canadians became “woke” to the treatment of Indians. The atrocities of World War II, recognition of the contributions of Indigenous soldiers to the Allied victory, and the inequality in veterans' services following the war caused Canadians to adversely judge the policies of the federal government. Information about the treatment of Indian children in residential schools and tuberculosis patients in Indian hospitals also began to emerge at that time. It was this period of awareness and outrage that drove the federal government, in 1951, to introduce amendments to the Indian Act that removed some of the more restrictive measures, including restrictions on forming political groups and hiring lawyers.

Despite being forbidden to form political groups prior to 1951, political groups were very much active and meetings were often held under the guise of bible study groups. Enforcement of the Act appears to have diminished by the late 1930s.

The Indian Association of Alberta held its first meeting at Wabamun on July 28, 1939, with delegates present from eleven reserves. The group grew out of the earlier League of Indians of Alberta. By 1945 IAA had locals on most Alberta reserves, and it developed into one of the most influential Indian groups in Canada. It sent delegations to the Joint Committee of the Senate and Commons on Indian Affairs in 1947 and 1960, and has been directly involved in obtaining revisions to the Indian Act, improved health and educational facilities, and other services for Alberta Indians. [1]

It is against this backdrop of an increase in public awareness of social injustices endured by Indians and the emergence of Indian political groups speaking out to protect their rights that the federal government initiated a commission to look into conditions on reserves and provide recommendations. In 1966 The Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada (known as the Hawthorn Report) was submitted to the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Hawthorn Report included 91 recommendations under the headings of General, Economic Development, Federal/Provincial Relations, Political, Welfare, and Local Government. Included were recommendations that status Indians should leave their reserves in order to join the Canadian economy. Another recommendation was the spending of considerable funds to increase the living conditions on reserves, but that the funds should be from provincial coffers, and that reserves should be treated as municipalities. It was the Hawthorn Report that introduced the term “Citizens Plus” to the bureaucratic lexicon.

Indians should be regarded as “Citizens Plus.” In addition to the rights and duties of citizenship, Indians possess certain additional rights as charter members of the Canadian community.

The Hawthorn Report

“Citizens plus” was coined, in part, to denote the preservation of the separate identity of Indians. The Report provided a vision of how to integrate Indians into mainstream society, while still maintaining special citizenship. The Indian leaders and individuals who consulted in good faith in the preparation of the Hawthorn Report did so with the belief that the outcome would be revisions to the Indian Act and acknowledgement of their priorities.

Following the Hawthorne Report, and due to the continued interest in the social and economic conditions of Indians, the federal government produced the ill-fated White Paper, which outlined Trudeau’s vision of a “just society”. In a “just society”, all Indians would be “equal” to other Canadians i.e. the distinct legal status “Indian” would be eliminated, the Indian Act would be repealed, all treaties would be voided, ownership of land would be transferred to Indian individuals, and the Department of Indian Affairs would be dismantled. Trudeau considered a legal provision of “citizens plus” as discriminatory towards Indians and Canadians and that the “separate legal status of Indians had kept the Indian people apart from and behind other Canadians.”

The wrath the White Paper elicited was formidable. The IAA responded with Foundation Document Citizens Plus by the Indian Chiefs of Alberta. From the preamble:

To us who are Treaty Indians there is nothing more important that our Treaties, our lands and the well being of our future generation. We have studied carefully the content of the Government White Paper on Indians and we have concluded that it offers despair instead of hope. Under the guise of land ownership, the government devised a scheme whereby within a generation or shortly after the proposed Indian Lands Act expires our people will be left with no land and consequently the future generation would be condemned to the despair and ugly spectre of urban poverty in ghettos. . . We refused to meet him on his White Paper because we have been stung and hurt by his concept of consultation. . .

In his White Paper, the Minister said, “This review was a response to the things said by Indian people at the consultation meetings which began a year ago and culminated in a meeting in Ottawa in April.” Yet, what Indians asked for land ownership that would result in Provincial taxation of our reserves? What Indians asked that the Canadian Constitution be changed to remove any reference to Indians or Indian lands? What Indians asked that Treaties be brought to an end? What group of Indians asked that aboriginal rights not be recognized? What group of Indians asked for a Commissioner whose purview would exclude half of the Indian population in Canada? The answer is no Treaty Indians asked for any of these things and yet through his concept of “consultation,” the Minister said that his White Paper was in response to things said by Indians.

The Red Paper was dramatically presented to the prime minister and full cabinet on June 4, 1970. Keep in mind that while it is not unusual today for Indigenous people, in full regalia, to sing, and drum on Parliament Hill or speak in their home language in Cabinet, it was extremely unusual in 1970.

On June 4, 1970, some 93 years after the signing of Treaty Seven, the Indian Association of Alberta, led by Harold Cardinal and backed by the National Indian Brotherhood, presented its Citizen Plus counter proposal to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and 13 members of the Cabinet in an historic confrontation in the Centre Block on Parliament Hill . . . The meeting began with Mr. Trudeau introducing the members of the Cabinet, and Walter Dieter, N.I.B. president, introducing the Indian representatives. Chief Jim Shot Both Sides of the Blood Reserve chanted an untranslated Indian prayer and then came the symbolic presentation: Chief Norman Yellowbird presented the Red Paper to the Prime Minister on behalf of the Indian chiefs of Alberta, while at the same time Chief Harry Chonkolay, dressed in treaty uniform, returned the green Indian Policy proposal to Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chrétien. Chief Chonkolay does not speak English. His comments, translated by Walter Dieter, went as follows: “I am returning the paper to Minister Chrétien. I completely reject it because this was designed by the government itself. At the same time we have our own set of ideas as to what the Indians should be doing for themselves and we have come up with a proposal. We do not need this any longer. Our people do not need the Indian policy paper. This is the reason I am returning to Mr. Chretien. [2]

When forced to withdraw the White Paper in 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau is said to have stated, “We’ll keep them in the ghetto as long as they want.”

The White Paper really was a continuation of the assimilation policies of the Indian Act as it advocated for the immersion of Indians into the existing body politic, assuring them that they would be “equal” and have the same rights, privileges and freedoms as non-Indian Canadians and therefore have individual “self-sufficiency” and proposed an end to the Treaties.

The Red Paper held strongly against assimilation and argued that Indian people had signed the historical treaties with the Crown as equals, that the treaties were sacred and that promises made in the treaties were everlasting. The Red Paper also presented a prescription for self-government and self-sufficiency through economic development and education.

The formal rejection of the White Paper and the resistance of the Red Paper is considered “an Indian Quiet Revolution.” However, in retrospect, the moment launched a period of vocal activism that eventually led to Aboriginal rights being included in s.35 (1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.

[1] Indian Association of Alberta, Archives Association of Alberta, https://albertaonrecord.ca/indian-association-of-alberta

[2] Alberta Indians Present “Citizens Plus” The Indian News Vol. Thirteen, No. Three, June 1970

Featured photo: Shutterstock

At the Liberal Party of Canada biennial convention in Montreal in February 2014, party members voted on a number of policy resolutions. Of particular...

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...

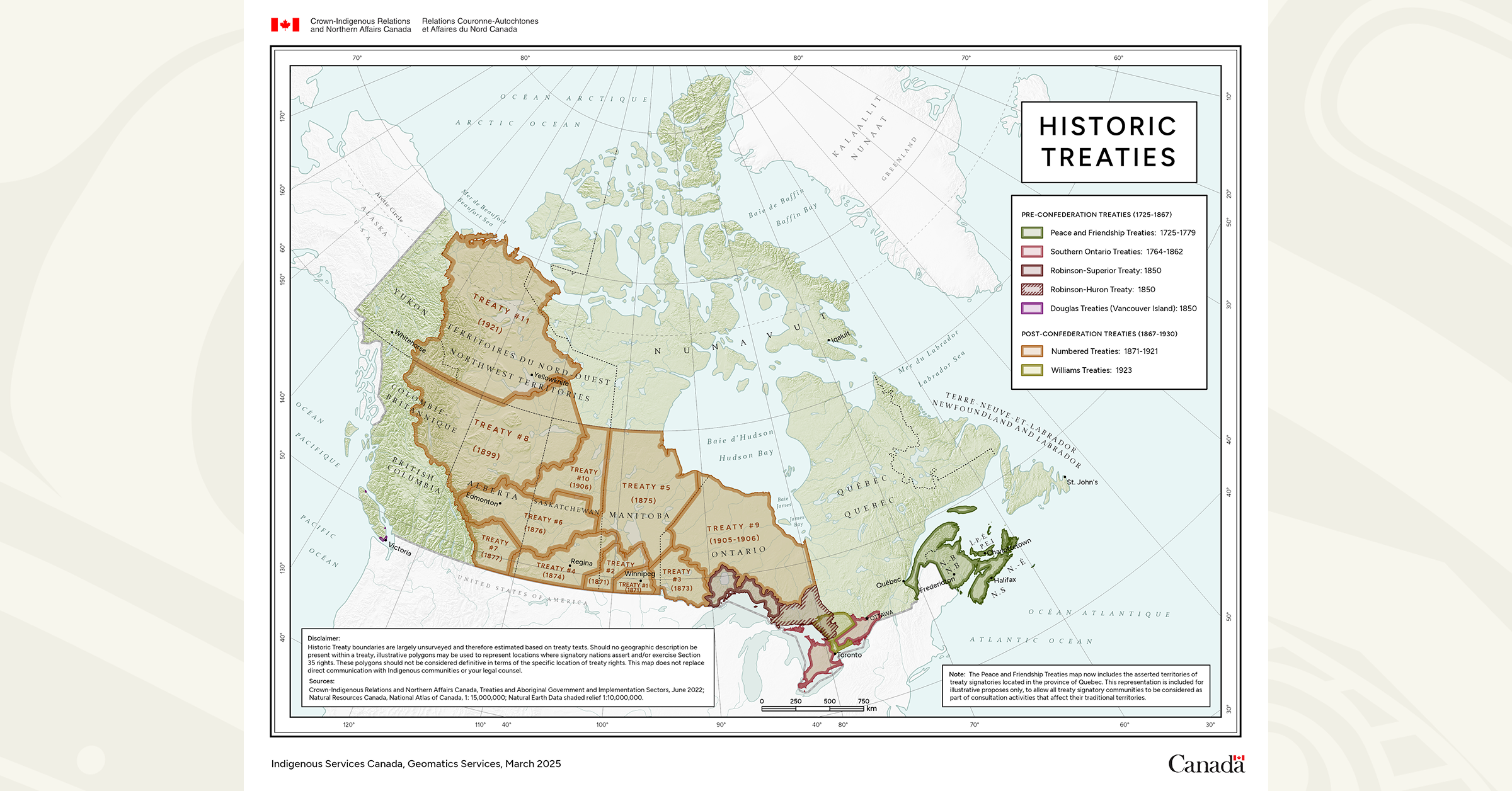

Treaty-making is not anything new in Canada. In fact, treaties pre-date the creation of the country and were instrumental in shaping what became...