The Indian Act & the Politics of Exclusion

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

We identify ourselves in many ways - by gender, generation, ethnicity, culture, religion, profession/employment, nationality, locality, language, hobby (biker, equestrian, knitter etc) and so on. We rarely identify ourselves in one category - it’s usually a combination of identities.

Identifying as an Indigenous person brings additional layers, complexities, and considerations. The added layers of identity can include but are not limited to whether or not a person has status, which nation, band, clan, tribal council or treaty office they belong to, and whether or not they live in their home community or have migrated to an urban centre.

-673158-edited.png?width=300&height=190&name=Indian%20Act%20and%20Indigenous%20Identity%20(1)-673158-edited.png) Here’s how I identify myself: I am a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw located between Comox and Port Hardy on Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland of British Columbia, I am an initiated member of the Hamatsa Society and am in line to become a hereditary chief. I am a status Indian.

Here’s how I identify myself: I am a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw located between Comox and Port Hardy on Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland of British Columbia, I am an initiated member of the Hamatsa Society and am in line to become a hereditary chief. I am a status Indian.

I feel it’s important to start with how Indigenous Peoples are identified by external agencies, rather than how Indigenous Peoples identify themselves. It’s necessary to understand the drive behind these processes and policies - which in essence was to arrive at a point where Indigenous Peoples, as a separate entity, ceased to exist, and were assimilated once and for all.

I switch to using “Indian” for historical accuracy as that was the legal term used by the federal government and continues to be used in the title of the federal policy that oversees almost every aspect of the life of a status Indian.

Initially, the criteria used to define who was or was not Indian were quite expansive. However, the federal government, over time, realized that narrowing the definition provided an effective means of reducing the number of people who met the criteria thereby advancing their goal of assimilation.

The first attempt at defining Indians was in 1850 in An Act for the better protection of the Lands and Property of the Indians in Lower Canada. The definition of Indian was broad and inclusive

- “any person of Indian birth or blood,

- any person reputed to belong to a particular group of Indians,

- and any person married to an Indian or adopted into an Indian family.“ [1]

Following the Depression and World War II, social awareness arose in Canada and the general public began to take notice of how Indians were treated, especially in light of their significant contributions in both World Wars. At this time, stories about the government-funded residential schools, the abuses, the high death rate, and the overall conditions were creeping out into mainstream society. A Special Joint Committee was established in 1946 to look into Canada’s policies regarding Indians, as well as look into the management of Indian Affairs.

Despite the recommendations of the Committee, the treatment of Indians did not improve under the Indian Act of 1951. It was at this time that a central registry for all people registered under the Act was established.

In 1956, the Government of Canada began issuing Certificate of Indian Status (status cards) as an official identity document verifying the cardholder as a status Indian who is registered under the Indian Act. [2]

The next revision of the Indian Act was in 1985 when An Act to amend the Indian Act (Bill C-31) was passed. The criteria used to define who was and who was not a status Indian was expanded considerably.

Women, under the Indian Act, were considered of little consequence, unless they were married to a status Indian. If they “married out” (1869 - 1985) to non-Indian or non-status Indian men, they lost their status, as did their children. If an Indian male “married out” they did not lose their status, and their wives and children gained status.

The 1985 amendments to the Indian Act resulted in an increase in the number of people eligible for status. That increase put additional pressure on reserve housing and other resources which were already under strain. Funding for those resources did not increase in accordance with the increase in those who met the criteria for status.

I haven’t touched on the relationship between status and band membership - that’s another article unto itself. But, as you can see, defining who was and who was not a status Indian turned out to be a much more complicated process than the government back in the 1850s ever imagined. The assumption was that the presence of Indians as separate and distinct was finite - that eventually they would be absorbed (assimilated) into mainstream society. That’s not quite how it went though. Resistance to assimilation was severely underestimated as was the determination to retain traditions and cultures despite the ever-increasingly punitive laws, rules and prohibitions that constrained the lives of Indians from their first to final breath. Some have even argued that having separate laws and lands greatly inhibited the assimilation process.

Now that you have an understanding of the motives and the methods used by the government to classify Indians it’s time to take a look at how those motives and methods impacted Indigenous communities, cultures, and traditions in terms of identity.

The assimilation policies caused deep and significant harm to the continuity of families, cultures, languages, and traditions - the very fabric of identity for most Indigenous Peoples. It’s estimated that 150,000 children were sent to residential schools. While at the schools those children were forbidden to speak their home language or practice their spirituality or traditions. When they returned home, many were too traumatized to speak their language, and a great many felt alienated from family and community. And so began the erosion of family and community bonds, language, culture and spirituality - of identity.

Indigenous individuals will often respond to “Where are you from” with the name of their band or nation, not the city, town, or province in which they live. It is also common to hear Indigenous individuals identify themselves in genealogical terms - who their parents and grandparents are. They rarely answer the question with the typical name, profession, and city response that is used by non-Indigenous individuals. Identity is not so much about personal identity as it is about where that person belongs in the collective identity of their band, cultural, or familial collectives.

From the perspective of the colonial governments, Indians were initially “savages”, then they were “children” but they were always “others.” Now Indigenous individuals and communities are moving towards self-determination. Communities are increasingly expressing that they are fed up with the historical interference in determining who belongs to their community. They no longer want bureaucrats in Ottawa telling them who are members and who has Indigenous identity.

There will be challenges because some people who were adopted out don’t know who they are.

Self-determination more than ever has become a political force for government to reckon with.

Indigenous identity is complicated but it is getting sorted out. The long-term solution will be self-determination by the communities and not legal decisions passed down by “others.”

As for myself, as an Indigenous person, I will figure out on my own how to fit into this country called Canada.

By Bob Joseph

[1] An Act for the better protection of the Lands and Property of the Indians in Lower Canada, 1850

[2] Library of the Parliament, Indian Status and Band Membership Issues; Megan Furi, Jill Wherret; Political and Social Affairs Division; February 1996, Revised February 2003

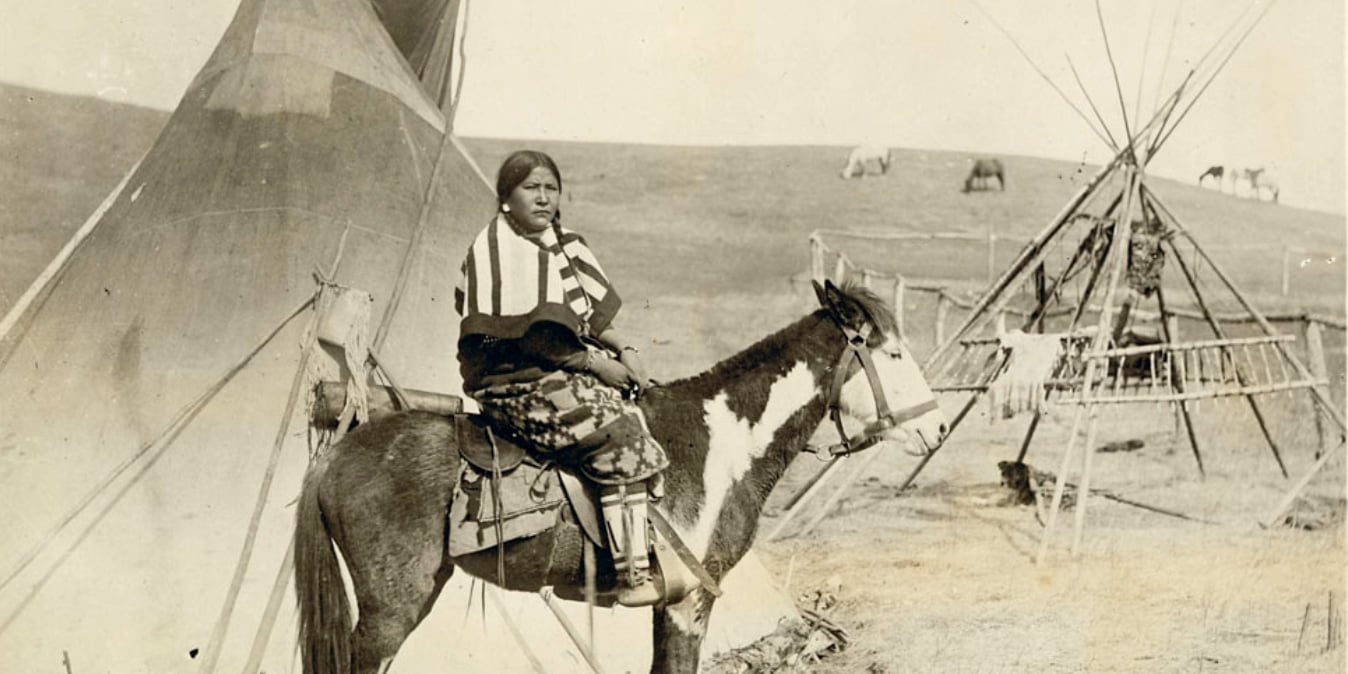

Featured photo: Unsplash

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

Long before the arrival of Europeans, confederation, and the imposition of the Indian Act, Indigenous communities were self-determining. They decided...

When an Indian woman marries outside the band, whether a non-treaty Indian or a white man, it is in the interest of the Department, and in her...