Indian Residential Schools: Merry Christmas vs. Happy Holidays

I wrote this article because I frequently see postings on Facebook asking people to “like” the “Merry Christmas” greeting and denounce the “Happy...

Fifty-eight percent of young adults living on reserve in Canada have not completed high school, according to the 2011 National Household Survey census results. And that’s an increase from the 2006 census results. How did this come about?

The root cause of today’s Indigenous education issues began with the passing of the British North America Act [1] in 1867. Prior to that, the relationship between the federal government and indigenous Peoples had been on a Nation-to-Nation basis. With the passing of the BNA, the relationship shifted significantly to Indigenous Peoples becoming wards of the Crown – and the federal government was given authority to make laws about “Indians and lands reserved for Indians”, thereby marking the beginning of the dark era of enforced cultural assimilation.

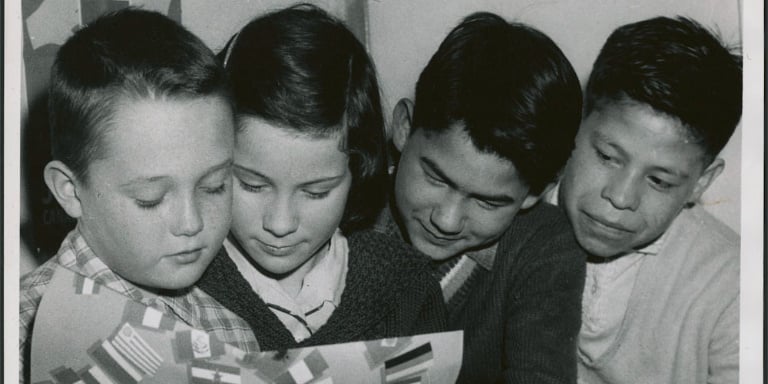

In 1884, Indian agents, under the direction of the Indian Act mandate, and later the RCMP, began forcibly removing children from families and placing them in residential schools. The “logic” behind the removal of over 150,000 children during this era (the last residential school closed in 1996) was that it was the best route to assimilation because it “…took the Indian from the reserve and kept him in the constant circle of civilization, assured attendance, removed him from the “retarding influence of his parents…” [2] In order for Indigenous People to be successfully assimilated into Euro-Canadian society, their cultures, languages, and traditions had to be taken away.

NOTE: In 2019, former students of Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet in what is now known as Nunavut won a court battle to have Kivalliq Hall included as an IRSSA-Recognized School. While this 2015 article states that the last residential school in Canada to close was in 1996, Kivalliq Hall's closing in 1997 is an important detail to note when recounting and learning about Indigenous history.

Indian residential schools provided at most a rudimentary education. The majority of the “learning” was focused on religious indoctrination and manual labour skills. The children who survived faced a harsh and lonely future – many had been sexually and emotionally abused, they could not return to their traditional lives as they had lost their language and traditions, and they did not have an adequate education so they were hampered in their ability to succeed socially or economically.

It is well documented that it takes consistent home support for a child to stay the course and graduate from high school. But what if the home is made up of adults who are direct and/or intergenerational survivors of the residential school system? Even if they did graduate it was often not with a great standard of education. This means they are less able to help their children with homework assignments, especially in the tougher subjects, and they may be less supportive in terms of encouraging their children to graduate.

The effects of the Indian residential school system are intergenerational, comprehensive, deep, and ongoing. The attempted assimilation process which directly impacted many generations not only underscored the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the government, churches, and the RCMP but implanted a deep distrust of schools, teachers and administrators.

The next time you hear about Indigenous education issues, understanding the issues will help answer questions about why they may not have a grade 12 education, why they may not be job ready, may not have a driver’s license, and may not be interested in attaining any of the above.

[1] British North America Act is now known as the Constitution Act

[2] Davin Report, 1879

Featured photo: Bob Joseph

I wrote this article because I frequently see postings on Facebook asking people to “like” the “Merry Christmas” greeting and denounce the “Happy...

In 1844, the Bagot Commission of the United Province of Canada recommended training students in “…as many manual labour or Industrial schools as...

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...