A Brief History of Treaties in Canada

Treaty-making is not anything new in Canada. In fact, treaties pre-date the creation of the country and were instrumental in shaping what became...

We have received requests to provide a description of the difference between historic and modern treaties. This article attempts to answer the question plus provide some additional background.

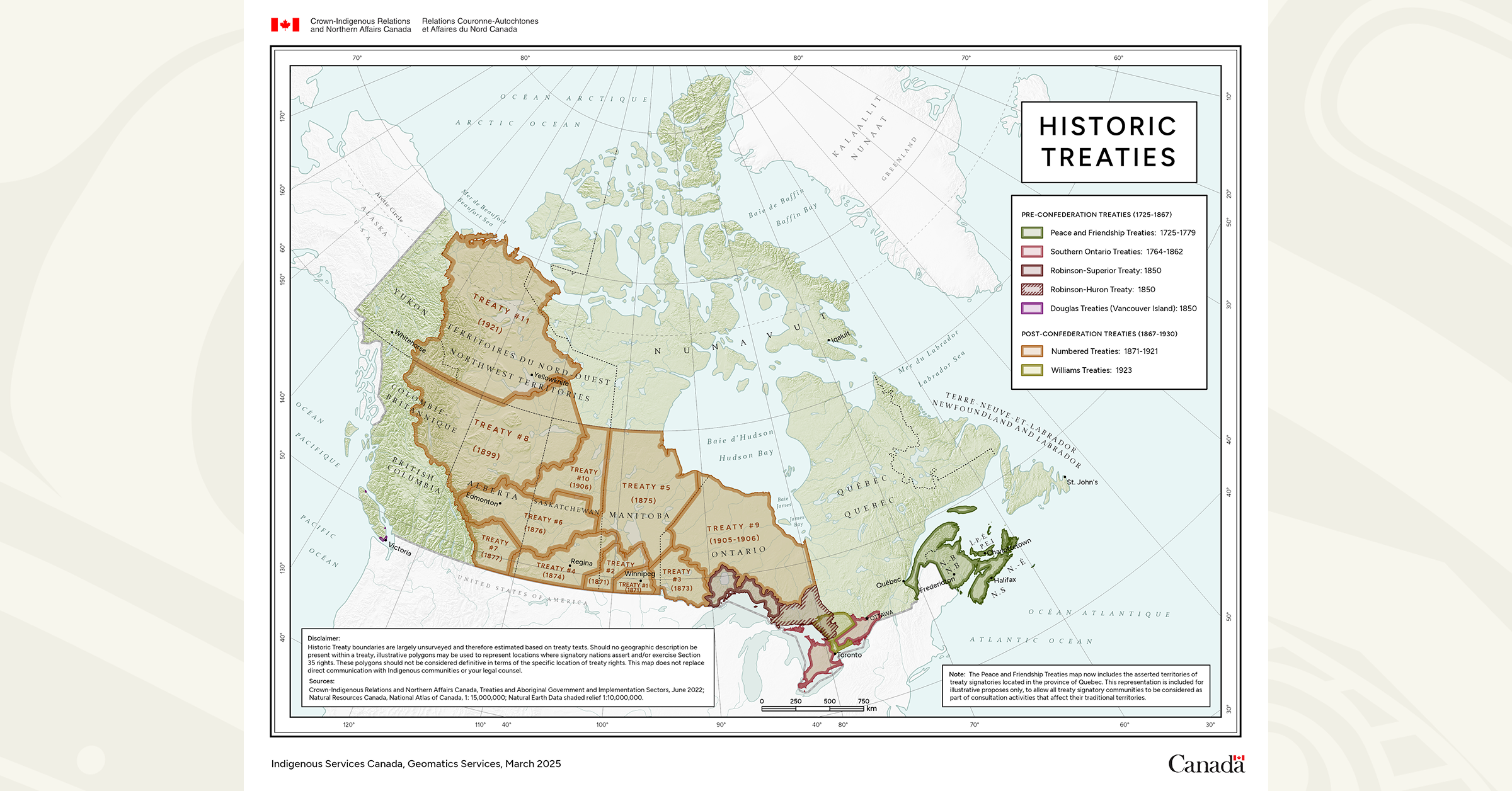

For terms of reference, historic treaties were made between 1701 and 1923. Historic treaties were marked in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and parts of British Columbia; the first modern treaty was signed in 1975.

When looking at historic treaties one has to keep in mind the era and the intent behind the parties involved. From the perspective of the Indigenous leaders who “marked” the treaties (they did not sign the treaties - as an oral society that depended on people honouring their verbal commitment signing a document was an alien concept), they knew their world, and the world for future generations of their people was changing. They negotiated in good faith for the survival of their people.

The chiefs who marked the treaties profoundly believed themselves to be entrusted by the Creator with the protection of their tribal cultures - the Creator’s blueprint for their survival and well-being. When they participated in the treaty-making process they did so from the conviction that they were honouring this sacred trust. In their minds, the treaty was an instrument for fulfilling this sacred obligation to the Creator, to their ancestors, and to generations yet to come. Another implicit understanding of the chiefs who marked the treaties was that they were autonomous peoples, and that the treaties affirmed the continuity of their autonomy. They marked the treaties in the spirit of coexistence, mutual obligation, sharing, and benefit, and as an agreement between themselves and the newcomers not to interfere in each other’s way of life. They assumed the treaties would enshrine this intent and spirit as a permanent and living legacy. Thus, as a frame of reference for justice, the treaties provide a paradigm of high idealism. [1]

The chiefs negotiated for what they anticipated would be needed for the continuation of their people as they transitioned from their formerly expansive self-determining, self-governing and self-reliant world to subsistence and dependence living on small reserves. The treaty articles they negotiated included education, economic assistance, health care, livestock, agriculture tools and agricultural training.

The other signatory, the Crown, had a different intent. Under John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, the intent was to remove Indigenous Peoples from their land, gain access to natural resources, open up the country for settlers, and to construct a railway from Upper Canada to the Pacific Ocean.

From the perspective of the government of Canada and of provinces, what the treaties said was this: First Nations give up all claim to the land, surrender absolutely any claim to the land, in exchange for which they would get, depending on the treaty, either 4 dollars or 5 dollars a year, the right to continue to live on a reserve, the right to continue to hunt on traditional territory and some sense that they were being protected by the crown. [2]

In some instances, the means used by the government to get the chiefs to mark the treaties brings into question about how the term “honour of the Crown” was interpreted by its representatives. For example, Treaty 6, which covers much of the Prairies, was signed during a famine which devastated the Indigenous population. The government withheld "emergency food rations from communities that did not sign the treaty... This was brutal, and it was effective. One after the next, Aboriginal leaders signed the treaty." [3]

Modern treaties, or comprehensive land claims, are negotiated in a dramatically different setting. Negotiators speak a common language. Indigenous negotiators can hire lawyers (formerly prohibited under the Indian Act from 1927 - 1951), and, Indigenous title to land they had occupied since time immemorial has been acknowledged by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1973 (Calder decision).

Since 1975, with the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, 26 other modern day treaties have been agreed to between the Crown and indigenous peoples covering nearly 40 per cent of Canada's land mass.

These agreements have provided for indigenous ownership of over 600,000 square kilometres of land, financial transfers of over $3.2 billion, co-management regimes, resource revenue sharing and law-making powers. [4]

The most telling difference between historic and modern treaties lies in the well-being of the people. Here’s some information on Community Well-Being (CWB) of historic versus modern treaty communities.

In 1981, Historic and Modern Treaty First Nations had similar levels of community well-being. However, between 1981 and 2006, the CWB index of Modern Treaty First Nations (+19) improved at nearly twice the pace of Historic Treaty First Nations (+10). Additionally, between 2001 and 2006, while progress in well-being virtually flattened for Historic Treaty First Nations, Modern Treaty First Nations kept pace with non-Aboriginal communities.

- On average, both Modern Treaty and non-Treaty First Nations display higher well-being than Historic Treaty First Nations.

- The well-being of Modern Treaty First Nations improved twice as fast as Historic Treaty First Nations between 1981 and 2006.

- Prairie Historic Treaty First Nations present the lowest well-being scores of a Treaty First Nations. [5]

So, there’s our attempt at a description of the difference between historic and modern treaties. Hope it helps!

[1] Meno Boldt, Surviving as Indians, The Challenge of Self-Government

[2] Bob Rae, The Gap Between Historic Treaty Peoples and Everyone Else

[3] ibid

[4] Kim Baird, Clint Davis, Jason Madden, Modern day treaties fundamentally reshaping Canada for the better, CBC Indigenous

[5] Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Community Well-Being and Treaties TRENDS FOR FIRST NATION HISTORIC AND MODERN TREATIES

Featured photo: Signing of the Treaty at Windigo, Ontario, 1930. Photo: Canada. Dept. of Indian Affairs and Northern Development / Library and Archives Canada / c068920

Treaty-making is not anything new in Canada. In fact, treaties pre-date the creation of the country and were instrumental in shaping what became...

Following every training session we ask learners if they would kindly take the time to fill in a survey about the training. We find these surveys...

June is National Indigenous History Month - a time for all Canadians - Indigenous, non-Indigenous and newcomers - to reflect upon and learn the...