Honourary Chief J. Wilton “Willie” Littlechild

Anyone aware of the work, life, and growing legacy of J. Wilton Littlechild will know that he is a significant leader in international Indigenous law...

It’s becoming more commonplace for formal meetings to begin with an acknowledgement of the traditional or treaty territory on which the meeting is being held. It’s good to see this really positive development on the increase because doing so signals that you recognize that community’s deep, historical and constitutionally protected connection to the territory.

I am frequently asked, “Do I get credit for trying?” No, because people in every culture are sensitive about how their names are pronounced so please make the effort to get the pronunciation correct. Doing so shows respect. It is also an acknowledgement of the connection between name, land and identity. In some cultures, when an Indigenous person introduces themselves they will speak first about the territory they come from, followed by their familial background and lastly about their self - people define themselves in relation to their land and their peoples.

For some guidelines on the usage of Indigenous terms and 43 definitions, download our free eBook: Indigenous Peoples: A Guide to Terminology.

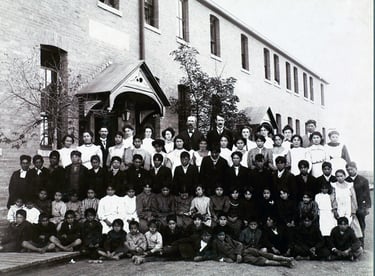

Many Indigenous languages are in danger of disappearing forever, due to the devastating effects of epidemics and the era of residential schools that prohibited multiple generations of Indigenous children from speaking their home language.

When most children entered the residential school system they primarily spoke their home language. However, when they crossed the threshold of these imposing buildings, all they knew, including their language, was forbidden. The educators were given the mandate that at all costs the children had to learn to read, write, understand and speak English. Punishment for speaking their language included, from the relatively mild washing of their mouths with soap to the inconceivable practice of piercing their tongues with sewing needles.

When children returned to their families for a visit or finished school, they frequently felt alien when with family members because they had been taught that their language, culture and traditions were evil and dirty. Many were so traumatized by the punishments received for speaking their home language they could not bring themselves to speak it at home. Residential school survivors began teaching their children English so that they would not suffer the same punishments when they were taken off to residential schools.

Back to the pronunciation of Indigenous names. Your research should start with determining the traditional name of the community - don’t assume that the name the community is commonly known as is its preferred name. For example “Kamloops Indian Band” is actually Tk'emlúps te Secwe?pemc; Patricia Bay First Nation is “Tseycum First Nation” - not all communities use their traditional names but most have signs at the entrance to their lands and the name they use will be on that sign.

At the community level, where contact between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples is often minimal or marred by distrust and racism, establishing respectful relationships involves learning to be good neighbours. This means being respectful—listening to, and learning from, each other; building understanding; and taking concrete action to improve relationships. At the Victoria Regional Event, intergenerational Survivor Victoria Wells said:

I’ll know that reconciliation is happening in Canadian society when Canadians, wherever they live, are able to say the names of the tribes with which they’re neighbours; they’re able to pronounce names from the community, or of people that they know, and they’re able to say hello, goodbye, in the language of their neighbours... that will show me manners. That will show me that they’ve invested in finding out the language of the land [on] which they live... because the language comes from the land... the language is very organic to where it comes from and the invitation to you is to learn that and to be enlightened by that and to be informed by [our] ways of thinking and knowing and seeing and understanding. So that, to me, is reconciliation. [1]

To hear how a community name is correctly pronounced, I always recommend people call the community office after hours and listen to the recording and practise, practise, practise. You could go one step further and enquire at the community office if there is someone you could hire to help you and your team learn some key phrases.

By following protocol and learning to pronounce Indigenous names you are supporting the community’s struggle to keep their language alive. The effort will not go unnoticed.

[1] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Summary Report, 2015, p 307-9

Featured photo: Flickr, Brandon O'Connor

Anyone aware of the work, life, and growing legacy of J. Wilton Littlechild will know that he is a significant leader in international Indigenous law...

1 min read

It is important for those who did not attend an Indian residential school to remember that the legacy of those dark halls did not end with Prime...

We recently received the following questions from a reader: Question: A few years ago I attended your workshop in Ottawa and bought your [Working...