Snapshot of Indian Act Denial of Status for Indigenous Women

When an Indian woman marries outside the band, whether a non-treaty Indian or a white man, it is in the interest of the Department, and in her...

3 min read

Bob Joseph July 09, 2012

Indian Act policies subjected generations of Aboriginal women and their children to a legacy of discrimination when it was first enacted in 1876 and continues to do so today despite amendments. Federal law in the late 1800s that defined a status Indian solely on the basis of paternal lineage - an Indian was a male Indian, the wife of a male Indian, or the child of a male Indian continues to be a quagmire of discrimination and disrespect towards women. While there have been numerous amendments to the Act, Indian status continues to be transmitted by male Indians, never by female Indians.

From 1869 until 1985 (116 years), if an Indian woman married a non-Indian man, she and the children of the marriage were denied Indian status. In 1985, the Indian Act was amended by the passage of Bill C-31 to remove discrimination against women, to be consistent with section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms[1], included in the 1982 amendment of the Constitution. Coming into effect on April 17, 1985, Section 15 provided that “every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and benefit of the law without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age, or mental or physical disability”.

The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) notes that strong concerns have been raised among Aboriginal people regarding Bill C-31’s effective replacement of original Indian Act discriminatory provisions with new ones:

For example, as noted in the Bill C-31 study summary report, “bands that control their own membership under the Act may now restrict eligibility for some of the rights and benefits that used to be automatic with status.” Moreover, sex discrimination, supposedly wiped out by the 1985 amendments, remains. Thus, for example, in some families Indian women who lost status through marrying out before 1985 can pass Indian status on to their children but not to their children’s children - the “second generation cut-off.” However, their brothers, who may also have married out before 1985, can pass on status to their children for at least one more generation, even though the children of the sister and the brother all have one status Indian parent and one non-Indian parent. [2]

Amendments to Bill C-31 provided a process by which women could apply for reinstatement of their lost Indian status. While such an amendment looks good on paper, it proved to be extremely difficult for women to actually execute the process. The first of many hurdles was the then Department of Indian and Northern Affairs’ documentation system - the numerous requests for additional information coupled with the department’s significant under-estimation of the sheer volume of applicants and its inability to process the applications due to inadequate staffing levels frequently left the applicants in prolonged states of limbo. Besides the daunting magnitude of red tape involved, a more heartless aspect of the reinstatement process was the cost applicants were forced to bear as they travelled from sometimes very remote communities to centres that had DIAND offices, plus the costs for research and documentation fees. These costs and travel requirements simply put the dream of reinstatement, which opened the door to better health and education services for the women and their children, out of reach for many who were already financially marginalized due to their lack of “status”.

Bill C-3, introduced in March 2010, was supposed to be the remedy but actually continued the discrimination because the status reinstated is of inferior status. Grandchildren born before September 4, 1951, who trace their Aboriginal heritage through their maternal parentage are still denied status while those who trace their heritage through their paternal counterparts are not.

These Bills do little to change the relationship between the Indian Act and women's status.

[1] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.), 1982, c. 11.

[2] Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Volume 4, page 37, 1996. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services, 2007, and Courtesy of the Privy Council Office.

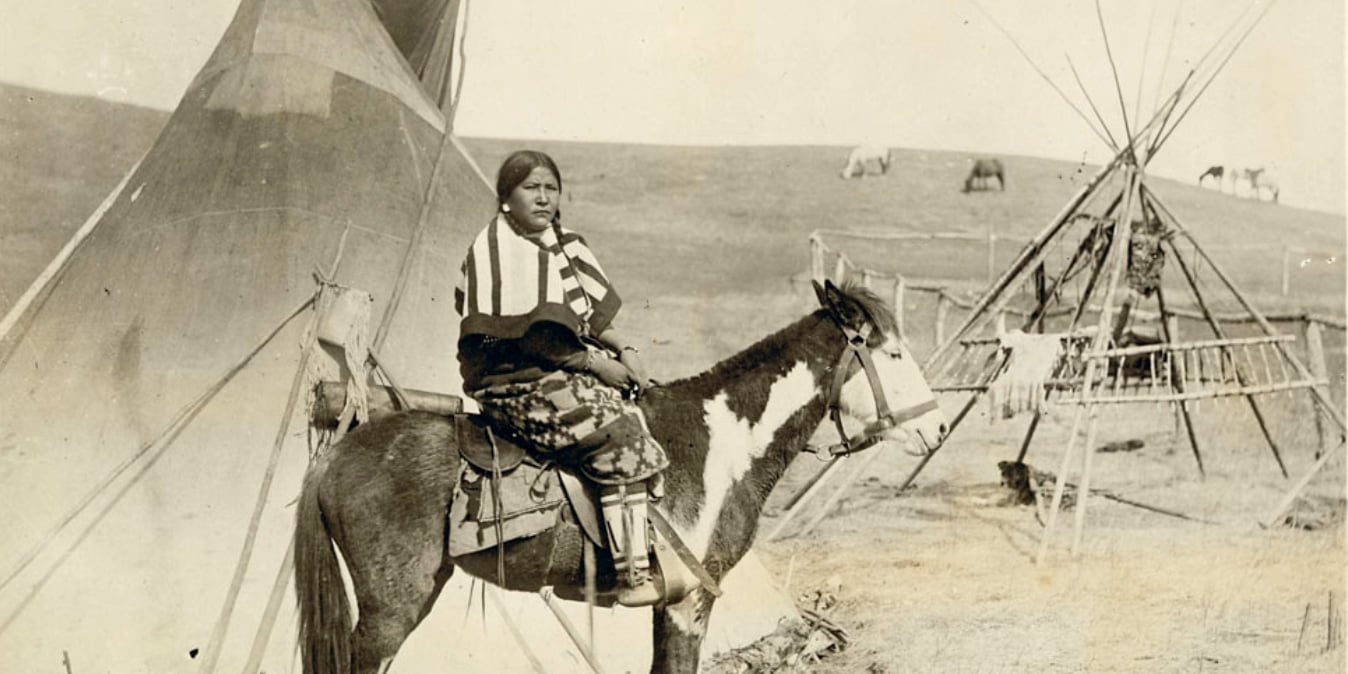

Featured photo: Chief Anna Whiteduck of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation standing in front of a house. Golden Lake Reserve, Ontario. 1960. Photo: Department of Citizenship and Immigration / Library and Archives Canada / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / e011308579 ; Copyright: Government of Canada

When an Indian woman marries outside the band, whether a non-treaty Indian or a white man, it is in the interest of the Department, and in her...

The Bank of Canada put out a call for nominations of Canadian women for a series of new banknotes. This is not the first time women have been...

By Bronte Phillips Changing their last names after marriage and sharing their bodies with their unborn children are two ways in which many women and...