A Brief Look at Indian Hospitals in Canada

We would like to acknowledge that this article was framed from the research and writing of authors Maureen Lux (Separate Beds: A History of Indian...

In 1844, the Bagot Commission of the United Province of Canada recommended training students in “…as many manual labour or Industrial schools as possible… In such schools…isolated from the influence of their parents, pupils would imperceptibly acquire the manners, habits and customs of civilized life.”

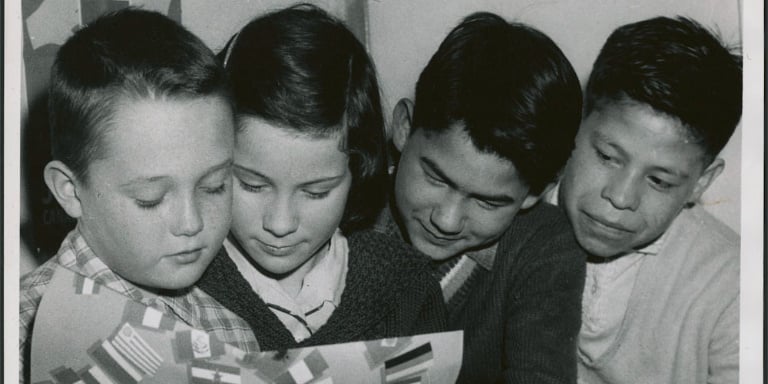

In 1879, the Davin Report recommended Indian residential schools based on the American model. Davin reported that the boarding school approach was the best answer because it “…took [the Aboriginal child] from the reserve and kept him in the constant circle of civilization, assured attendance, removed him from the “retarding influence of his parents ...” By, 1931, 80 residential schools existed throughout Canada. Requiring Indigenous children to participate in the public school system was seen as an important instrument of the assimilation policy, and compulsory attendance was incorporated into the Indian Act early in the twentieth century. Keep in mind that all of these measures were justified in part by officials as being measures designed to help Indigenous Peoples and bring them forward. The approach was, “We’re from the government and we are here to help.”

In the grand scheme of things, Indigenous Peoples are not further ahead when you consider prior to all the “help” they were self-determining, self-reliant and self-governing. Since it was widely assumed in the 1920s by non-Indigenous people that the Indian didn’t have the “physical, mental or moral get-up to enable him to compete,” as one Indian Commissioner phrased it in a report to Ottawa, the only thing to do was to teach him a trade. Taking their grant money, the priests quickly set up residential schools – as far as possible from the bad influence of home, family, and friends. Indian children right across the country shared the common trauma of being dragged away from their homes and cast into strange places, where they were beaten if caught speaking their own languages. Since the residential schools were all denominational, Christian indoctrination was the main focus: learning a trade became a poor second. Not surprisingly, children ran away from the residential schools in droves. So many escaped that the RCMP were used to chase them down and haul them back into classes. The “problem” of escaping children got to the point where the government passed a law stating that Indian parents had no authority over their children while the children were in residential school. The situation would have been enough of a nightmare for parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and children alike, even if it had not been coupled with the fact that non-Indigenous people had built such sub-standard buildings into which to herd a captive generation of young Indians that many of the children became sick and died.

In 1914, Duncan Campbell Scott, former Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs confessed:

"…the system was open to criticism. Insufficient care was exercised in the admission of children to the schools. The well-known predisposition of Indians to tuberculosis resulted in a very large percentage of deaths among the pupils. They were housed in buildings not designed for school purposes, and these buildings became infected and dangerous to the inmates. It is quite within the mark to say that fifty per cent of the children who passed through these schools did not live to benefit from the education which they had received therein.” [emphasis added]

In 1951, the federal government began a four-decade-long process of shutting down the schools; the last residential school for Indigenous children closed in 1996. Many of today’s Indigenous People and leaders are survivors of the residential school program. Although the last of the schools closed in 1996, the effect of the residential school system is intergenerational. Those children who were born after the closure of the schools were born to parents who likely attended and survived these schools. Following generations of Indigenous children are learning their values, behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs from parents who felt abandoned by their own parents and communities, and abused by the church and state.

NOTE: In 2019, former students of Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet in what is now known as Nunavut won a court battle to have Kivalliq Hall included as an IRSSA-Recognized School. While this 2012 article states that the last residential school in Canada to close was in 1996, Kivalliq Hall's closing in 1997 is an important detail to note when recounting and learning about Indigenous history.

The well-known psychologist, B.F. Skinner believed that we are all products of our environment. Children raised in a loving and supportive environment will more likely become loving and supportive adults and parents. Unfortunately for the majority of the survivors of residential schools, they were not raised in such an environment and therefore are likely without the skills to provide a loving and supportive environment for their children. A lot of the social ills (i.e. alcoholism, violence, verbal and sexual abuse, and suicide) found in Indigenous communities have their roots firmly placed in the dark halls of the residential school system.

Featured photo: Two Cree girls in their beds in the girls' dormitory at All Saints Indian Residential School, Lac La Ronge, Saskatchewan, March 1945. Photo: Bud Glunz / National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque / Library and Archives Canada / PA-166582

We would like to acknowledge that this article was framed from the research and writing of authors Maureen Lux (Separate Beds: A History of Indian...

I wrote this article because I frequently see postings on Facebook asking people to “like” the “Merry Christmas” greeting and denounce the “Happy...

The term “Sixties Scoop” refers to the period from 1961 through to the 1980s that saw an astounding number of Indigenous babies and children...